“Let’s jump on a plane to Edinburgh,” says Rob Williams. “You and me—let’s go! I was actually considering dropping everything and going over there to be part of what’s happening in Scotland.”

Williams is a Vermont secessionist. As far as he knows, he is the only elected official in Vermont—he’s on a school board—who avowedly favors the state’s divorce from the union, a return to its pre-1791 status as an independent republic. The idea was starting to catch on in the Green Mountain State when George W. Bush was president. It faded after Barack Obama replaced him. The reasons were not mysterious.

Then came the Scottish referendum. Secessionists like Williams had followed the Scottish National Party for years, as it first won concessions, then elections, then the right to an independence vote. In the last month, finally, polls showed the yes campaign creeping into a lead. If Scotland could secede, why not Vermont?

“The Scottish referendum has really captured a lot of attention and helped make secession look like a viable and sexy alternative to empire and centralization,” says Williams. “We’re not talking about secession in Yemen or Sudan, or some place Americans consider less relatable. We’re talking about Scotland! Making secession sexy in the West is fantastic. If the Scots do vote to secede, it proves that some Western nation under the yoke of empire can exercise its sovereignty and choose to leave.”

It’s been a while since secession fever broke out in America. The media hasn’t been particularly interested in it since brief periods after Barack Obama’s wins, when polls could find nearly half of Republicans in Texas or other red states ready to secede. In 2012, 80,000 Texans signed a nonbinding petition asking for secession; coverage of this did not always mention that more than 26 million people live in Texas.

Still, the reasons for Scotland’s crisis are the reasons why perfectly normal Americans become convinced that their states should leave the union. The reasons why it might fail are the reasons why the American secessionists are on a 149-year losing streak.

“I don’t know what would be sufficient to really move people toward secession,” says Kirkpatrick Sale. He should know: His Middlebury Institute has held multiple conferences on secession, and he’s published books about the idea, full of arguments that have bounced right off the skulls of average Americans.

“If the condition of this country as it is today is not enough to make people want to leave it, I cannot tell you what would,” says Sale. “If you have no faith in your central government; if Congress has the support of 10 to 12 percent of the public; if the president’s approval numbers are close to 30 percent in some states; I don’t know why this resentment doesn’t translate into secession, which is the only reliable peaceful way to make change.”

Other secessionists are more hopeful. Start with the Texas Nationalist Movement, which has been in close contact with the Scottish nationalists for years, and which is currently using the referendum as a PR and recruitment tool.

“We are, here in Texas, where Scotland was many years ago,” says Daniel Miller, president of the Texas group. “People continually told the Scots that this can’t happen, that this is a pipe dream. And then the people of Scotland put their minds to it. That’s been one of the major recurring themes of our message—this is not just about Texas independence, but about how independence and self-determination are the global trends of our time.”

Miller concedes that his Texans need to do far more of the legwork and math that Scottish nationalists did, to come up with proof—though they know it to be true—that an independent Texas would be wealthy and energy-independent. But Miller has led the Texas secessionists since 2001, from the time a Texan sat in the Oval Office—not ideal for recruitment—to the momentum-building reign of President Obama. His experiences, and the struggles of blue-state secessionists, have echoed in Scotland. Scottish voters roundly rejected the Conservative Party in 2010’s national elections, giving them only one of 59 parliamentary constituencies. The Scottish National Party’s leader, Alex Salmond, has promised Scots a social-democratic future for Scotland, one in which the Tories could never rule them. And it’s worked—the yes vote finally surged as Labour voters became warmer to it.

American secessionists realize that they need the luck of time and place. The Alaskan Independence Party has performed most strongly when voters have been angriest with the feds. Cascadia Now, a campaign to create a new country from the greenest parts of the Pacific coast, has attracted the most attention when it’s looked like Republicans were going to ruin everything for Greater Portlandia.

“The most powerful moment we’ve had was when the government shut itself down,” says Brandon Letsinger, director of Cascadia Now since 2005. “We’ve never gotten more hits on our webpage than when that happened. If they can’t get it together, maybe we need something else. So if the Republicans sweep both the House and the Senate, then I really expect our momentum will pick up and take off.”

The Scottish referendum, according to Letsinger, is drawing up a “great game plan to use in a future Casacadia 2020 campaign.” Ideally, it would happen in some Ted Cruz-run dystopia, from which liberals could not wait to flee.

But dystopia may not be enough to shake people loose from the United States. For a little while in the Bush years, a group called Christian Exodus attempted to gather a critical mass of believers to build a new society and country out of a red state. They tried South Carolina for a while, then Idaho. Then, they moved on to a campaign of “personal secession” at home and nullification of federal laws in the states. Ask Christian Exodus’ old executive director Keith Humphrey and he’ll tell you: Secession was never going to work.

“The people who could have made it work had places to live, commitments at home,” he says. “They couldn’t move. The people willing to move were the kind that had nothing left to lose. They’d already burned bridges with family and friends. They were not very employable. They were not ready for self-government, because many of them were getting government benefits.” Humphrey laughs at the debacle. “All these people who love liberty, and they’re on food stamps! How do you reconcile that ideal with that reality? If all the people involved have a socialistic mindset, then you can’t tell them they’re better off going independent.”

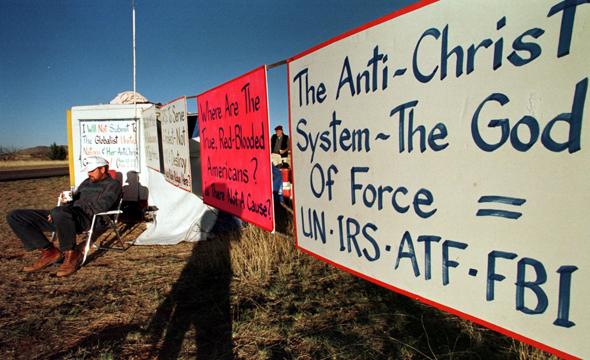

That wasn’t the only problem. In the South, says Humphrey, too many of the would-be-secessionists’ neighbors held a “reflexive support for war overseas.” Sure, it didn’t help that the go-to story of secession was the Civil War, and that in South Carolina and beyond, secessionists were tarred whenever the League of the South gave them a call. The larger, existential problem was that secessionists were trying to create a smaller and more isolationist country that would not, to use Kirkpatrick Sale’s term, continue “the empire.”

That’s a deal-breaker for the average American conservative. It’s less of a problem for secession-curious progressives. It’s just no problem at all in Scotland, where Salmond and the SNP have said, for years, that a newly independent country would say no to foreign wars.

“We’re facing a breaking point in the econ system when it’ll be impossible to pay for entitlements, starting with Obamacare,” says Humphrey. “The future that we’ve been talking about is coming true. For years, people would mock us and say, ha-ha, look how crazy those Christians are. Now it’s not crazy.”