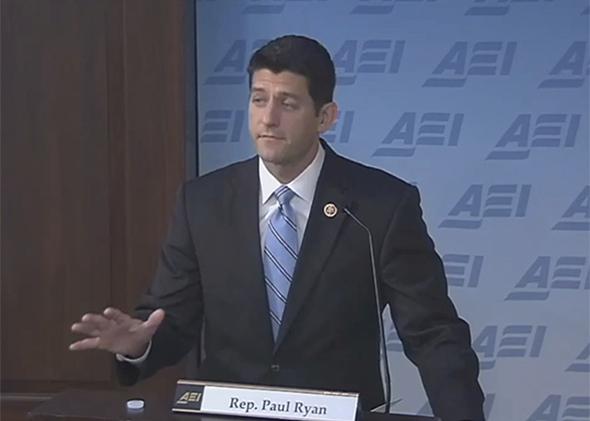

On Thursday, speaking in front of a packed house at a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C., Rep. Paul Ryan unveiled his latest plan to overhaul how the federal government addresses poverty. At the center of the Republican’s sweeping proposal was a pilot project that allows states to consolidate federal food stamps with 10 of the government’s other, large-scale anti-poverty efforts into a single, supersized “opportunity grant” program. The GOP’s reigning policy wonk explained to the friendly crowd that the move would cut red tape and give state and local officials the flexibility they need to maximize the impact of each federal dollar spent. “My thinking is, get rid of these bureaucratic formulas,” Ryan said. “Put the emphasis on results.”

The Wisconsin legislator also offered a second message to Democrats listening on Capitol Hill: Any state that opted into his pilot program, Ryan vowed, “would get the same amount of money as under current law—not a penny less.” That promise was aimed at putting his colleagues across the aisle at ease and enticing them to join his reform-minded debate. The problem is that there’s little to suggest that Ryan would keep his promise—in fact, history suggests he wouldn’t be able to even if he wanted to.

Ryan’s deficit-neutral pledge doesn’t extend any further than the specific, 73-page “discussion draft” (as he’s calling it) that he was waving from the American Enterprise Institute podium. The three-hole-punched elephant in the room was another lengthy white paper the House Budget chairman wrote: his 2015 budget blueprint, released less than four months ago. That proposal called for $137 billion in cuts over the next decade from the federal food stamp program, now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. A cut of that size—nearly a fifth of SNAP’s current budget—would mean millions of low-income Americans would lose at least some, if not all, of their benefits.

Pair Ryan’s budget with his awkward (and arguably racist) entrance into the poverty debate earlier this year, and Democrats have every reason to be skeptical of the House Budget chairman’s newest proposal. “How do you seriously say you care about anti-poverty when you’ve spent the last several years cutting the safety net?” Massachusetts Rep. Jim McGovern said in a conference call with reporters. “Our skepticism comes from the fact that the person who is saying all these nice things has voted in a way that has made life for poor people more difficult.”

But even if we set Ryan’s voting record and budget proposals aside, there’s still reason to doubt that his plan could deliver on its promise to leave the $800 billion the federal government currently spends on food stamps, housing assistance, and other social welfare programs untouched. That’s because if you strip away the “opportunity grant” cover Ryan wrapped around his latest proposal, you’re left largely with a traditional block grant program, whereby the feds hand over a lump sum of cash to the states to spend however they want within a relatively loose framework. That’s a proposal Ryan has offered before, and one that has proved to be a nonstarter for Democrats. (Ryan bristled at the block grant comparison when a pair of otherwise supportive panelists made it during an AEI roundtable immediately following his speech, but the best the congressman could do in the moment was to say that what he has in mind isn’t “your garden-variety block grant where you cut a check to the states and call it a day.”)

That’s because the accountability of Ryan’s block grant switch comes with something he appears to covet even more: an end to food stamps as an entitlement program. Under the current setup, any American who qualifies for SNAP benefits receives them, regardless of how much money Washington has already spent on the program that year. But switching to a block grant would effectively set a cap on SNAP spending by stopping the program from automatically increasing along with need. That, critics warn, could leave the program unprepared and underfunded when the next economic downturn sends more Americans than expected scrambling to put food on the table.

The best case for those who want to protect SNAP and other social welfare funding would be for Congress to freeze current funding levels for the foreseeable future. That technically wouldn’t be a reduction in funding, but inflation would tell a different story. That’s what happened to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program during Washington’s last attempt at major welfare reform. Since that program was block-granted in 1996, funding has remained pretty much flat at $16.6 billion per year while the program has quietly lost nearly one-third of its spending power to inflation. Under Ryan’s proposal, food stamps would risk a similar fate.

And that’s not the only reason that the anti-poverty crowd should be nervous. As Vice President Joe Biden’s former chief economist Jared Bernstein has already warned, once you put all of the social welfare programs in one package, you give lawmakers a single target to train their budget-cutting sights on. While Ryan’s plan may not explicitly cut the social safety net, it would make it much easier for him and his colleagues to do so in the near future.

Robert Greenstein, the president of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, raises a second, related issue, namely that even if federal funding somehow did remain constant in an opportunity-grant world, total funding—that is from federal, state, and local levels combined—would likely still dwindle. Greenstein says that’s because Ryan’s program would “afford state and local officials tantalizing opportunities to use some block grant funds to replace state and local funds now going for similar services.” Such decisions have proved relatively common under TANF since it was converted to a block grant. (Greenstein also raises a handful of smaller concerns with Ryan’s plan here, including the possibility that local officials would look to spend some of the former SNAP cash on less pressing proposals favored by politically influential developers.)

To be fair, Ryan’s proposal contains a number of common-sense reforms that already have support from both sides of the aisle, things like sentencing reform and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit. But if Ryan means it when he says he hopes his proposal kicks off a good-faith bipartisan debate about how Washington can better combat poverty, he’s going to have to make it a more honest conversation than he did on Thursday. The 47 million Americans currently living off of food stamps deserve at least that much.