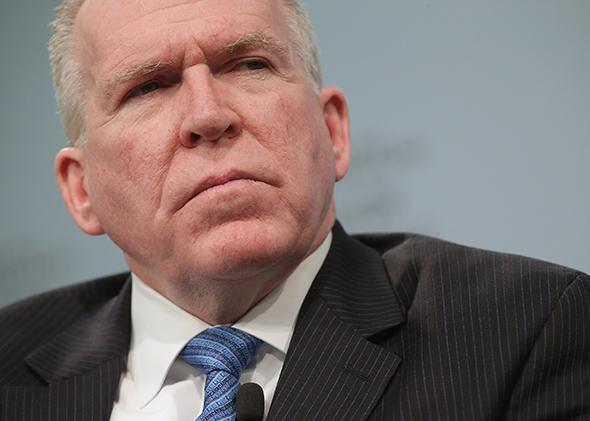

On Thursday morning the CIA stopped hiding the truth. According to an internal investigation, the agency had peered into the Senate Intelligence Committee’s computer network. Yes, it was sorry, and yes, it would form an accountability board led by former Sen. Evan Bayh, though it was unclear how that move would restore anybody’s confidence in government. CIA Director John Brennan had lied when he’d called the hacking “beyond the—you know, the scope of reason in terms of what we would do.”

Meanwhile, privacy advocates were considering whether a National Security Agency reform bill—the biggest potential victory for that loose coalition of watchdogs in years—relied on too much faith in the government’s good nature. More than a year had passed since NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden’s first leaks, and since a near-miss House amendment nearly nixed funding for bulk metadata collection. Vermont Sen. Patrick Leahy, who chairs the Judiciary Committee and who was elected in the backlash to Watergate, had debuted his version of the USA Freedom Act, and privacy groups had gotten behind it.

But were they starting to be taken for granted? A day before the bill was released, privacy groups were given an advance, embargoed look at what it would contain. Many of them signed on to a letter in support of Leahy’s bill. They’d asked for the House’s USA Freedom Act to be improved, and they claimed it had been. The New York Times was on board, too. Yet at least one group debated whether to remove itself from the letter, and others (who avoided signing it) are debating whether they should try to sink the bill.

“We’re concerned about some of the vague language in the bill,” said Erik Martin, general manager of Reddit, “and aren’t supporting at the moment.”

The dissenters saw problems that defied the talking points. The main thrust of the legislation, obviously, was that Leahy would prohibit the bulk metadata collection justified under Section 215 of the Patriot Act. Not bad, but there were, theoretically, other ways to get data—Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act (which made the PRISM program possible) and Executive Order 12333 (which allows the collection of data for non-U.S. persons). National security journalist Marcy Wheeler, who had called the House’s bill “USA Freedumber,” read the bill and spotted the ways that it “would permit the contact chaining on phone books and calendars, both things we know NSA obtains overseas, both things NSA might have access to through their newly immunized telecom partners.”

At best, the bill was not a step back, and avoided codifying some of the NSA’s bad practices. (That was a problem everyone had with the House’s bill.) “The bill does contain transparency provisions for 702, and it helps lay the groundwork for future reforms,” said a Leahy spokeswoman, “but it does not comprehensively address all the concerns for 702.” No one pretended otherwise.

“We weren’t expecting, at this point, comprehensive 702 reform,” said Amie Stepanovich, senior policy counsel at the pro-USA Freedom group Access. “It’s better addressed as part of a comprehensive package aimed at 702, something that we can argue separately. There’s some reform now—the call detail program is shut down.”

What prevents the government from finding a new loophole? Nothing, which is why some privacy groups feel like Sisyphus’ rock keeps rolling down the hill. The privacy groups, encouraged that the Senate’s bill was less horrid than the House’s, encouraged it to be passed without more changes. That was at odds with the advice of Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden and Colorado Sen. Mark Udall, who wanted another bite at Section 702. “Congress clearly intended this authority to be used to collect the communications of foreigners—not Americans,” they said, “yet the Director of National Intelligence recently confirmed that the NSA, CIA, and FBI conduct warrantless searches of communications of Americans that are swept up under this authority.”

According to Elizabeth Goitein, whose Brennan Center for Justice had signed the pro-Leahy letter, there just weren’t many good options for reformers. “Defining bulk collection is no simple task,” she said. I feel that this bill does the best possible job that could have been done under the circumstances. It should work to prohibit the bulk collection—what people understand to be bulk collection. But the bill doesn’t pretend to address communications intel, which can either be captured under Section 702 or 12333. That absolutely needs to be addressed.”

When can that happen? Maybe in 2016, when the Patriot Act comes up again. Maybe if there’s another window opened by a fresh outrage. It took long enough to get this bill—would killing it really produce a better one? On Thursday, on the way out of a House Republican meeting, USA Freedom’s House sponsor Rep. James Sensenbrenner acknowledged that the bill disappointed some reformers.

“It closes the door more, but not completely,” said Sensenbrenner. “There’s a little bit of dissension, but I think a lot of the dissenters are trying to make the perfect the enemy of the good. Look, I worked on this. I got the House to pass it in the form it did. It was a choice of either doing that or not having a vote at all.”