In my legal career, I’ve suffered two painful defeats litigating against the Republican political machine of Florida. The first was a case called Bush v. Gore. The second—less famous, but just as bitter—came two years later, in 2002, when I worked on a legal challenge to Florida’s absurdly partisan redistricting plan, only to see our claims rejected by both the state and federal courts.

So last week’s court ruling overturning gerrymandered congressional districts in Florida gave me a serious case of déjà vu for several reasons. First, its author was Leon County Circuit Court Judge Terry Lewis—a major figure in the post-2000 Florida election litigation miasma, who ultimately wound up overseeing the statewide hand recount of ballots that the U.S. Supreme Court halted in its infamous 5–4 order. Second, the ruling represented a long overdue vindication of our 2002 claim that the Florida Legislature had abused its power in entrenching its control over the state through redistricting.

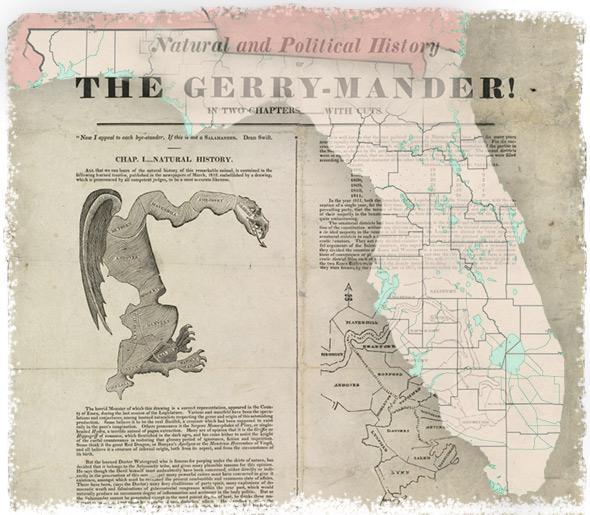

While much of the coverage of Lewis’ opinion has focused on the Florida legislative “chicanery” that it laid bare, a more substantial question is this: Why did this case strike down a hyper-partisan districting plan, when virtually every other such court challenge, in virtually every other state, has failed over the past three decades? How was the widespread bastardization that allows “representatives to pick their voters, instead of voters picking their representatives” finally checked by a court decision?

The key, as Lewis’ opinion makes clear, was the 2010 addition to the Florida Constitution known as the “Fair District” amendments. The Fair District amendments provide (in part):

No apportionment plan or district shall be drawn with the intent to favor or disfavor a political party or an incumbent … districts shall be compact; and districts shall, where feasible, utilize existing political and geographical boundaries.

It was this language that Lewis relied upon to strike down two specific congressional districts crafted by the Florida Legislature (while upholding several others) due to the way in which those misshaped districts were drawn under the thinly disguised guidance of political operatives and consultants.

The Fair District amendments were added to the Florida Constitution by referendum in 2010, in a public campaign that had wide bipartisan and nonpartisan support—but relied most heavily on substantial help from progressive donors, groups, and labor unions. Liberal groups backed the Fair District amendment because the Florida Legislature and congressional delegation were so stacked to the right—more than two-thirds Republican in a state that is infamous for being exactly 50-50 in overall partisan preference—that they believed any fair districting would be an improvement.

Perhaps there is no political process reform that could be more beneficial but is less appreciated by progressives than redistricting reform. The comparison to that progressive cause-of-the-heart—campaign finance reform—is telling. Every day email inboxes are flooded with requests for donations and updates on efforts to overturn Citizens United or pass some sort of campaign finance reform. Last week, the Democratic-led Senate Judiciary Committee voted to overturn the case by amending the U.S. Constitution, an indication of the priority assigned to this issue.

But while I too oppose Citizens United and decry the influence of special interest money in politics, I can’t get past this mathematical reality: Almost 90 percent of the House Republicans who are fomenting for gridlock, impeachment, and lawsuits against President Obama (instead of passing legislation) will win re-election in 2014—not because of a check written by the Koch brothers—but because they are in all-but-unopposed, one-party districts. Heavily partisan districts not only protect incumbents, they push the Republican majority further to the right: Just ask Rep. Eric Cantor what he thinks about his gerrymandered, post-2010, heavily Republican-conservative district … and ponder what that gerrymander in Virginia did to comprehensive immigration reform nationwide.

And while outrage over the electoral reform issues like long lines at the ballot box and voter disenfranchisement are justifiable, shouldn’t there be equal outrage for the fact that—if and when voters make it through the line and into the voting booth—as many as 80 percent of them will cast a meaningless ballot in an election where candidates faces only token opposition (if any opposition at all)? That, too, is due to partisan districting.

Why haven’t progressives taken up redistricting reform with the same passion devoted to campaign finance reform or electoral reform? There are largely two reasons.

First, unlike big money in politics, or voter disenfranchisement—evils that appear to overwhelmingly disadvantage Democrats—the immediate partisan consequences of gerrymandering are murkier. In some states, Democratic legislatures and governors have used gerrymandering to increase Democratic seats in the state legislature and Congress. Gerrymandering is an abuse of democracy that has a “two can play at that game” feel to it.

Second, and more delicately, there is the tricky question of race and districting. A combination of the Voting Rights Act and an uneasy alignment of black Democrats and white Republicans in some places has led many Southern legislatures to compact black voters into majority-minority districts (and leave others districts without large Democratic populations). That is why, for example, while many Democrats in Florida hailed Lewis’ decision, Rep. Corrine Brown—whose district was invalidated by it—was harshly critical.

The legitimate concerns of Brown and others reflect a painful history. When I represented biracial coalitions in Florida and Virginia in redistricting litigation a decade ago, tensions were still high from the days when white Democrats ran Southern legislatures, and showed little concern for the views of the their black Democratic colleagues. Today, reforms that redraw districts into more compact and logical boundaries could produce more competitive districts—but potentially fewer black legislators. The Voting Rights Act must be enforced to prevent that, and redistricting reform should never be a tool to undermine that civil rights safeguard.

Nonetheless, I have long believed—and now believe, more than ever—that progressives have much to gain from redistricting reform. And this goes beyond the mere hope that fairer districts would mean more Democrats in Congress.

At a time when voter cynicism about politics feeds cynicism about government, the crass ability of parties in power to impose an outcome on voters through gerrymandered districts magnifies that cynicism. At a time when voters feel distant from their elected officials, far-flung districts that do not adhere to any established sense of community add to the estrangement between representative and the represented. At a time when voters feel powerless to come together to organize for change, districts of vast size and disparate interests make it harder for citizens to unite and influence their leaders—and easier for those self-selected leaders to be the only thing voters share in common. And at a time when participation is already lagging, noncompetitive districts depress voter turnout and citizen engagement: It is hard to believe that your voice or your vote matters … when it really doesn’t because the districting plan makes the seat a “lock” for a member of the preferred party.

While all these observations are applicable to both conservative and progressive gerrymander victims—depending on who has drawn the lines—the overall impact is asymmetric because gerrymandering weakens the communitarian sentiment that is at the heart of progressive policy making. Put another way: If gerrymandering leaves voters feeling like the government is run by someone else, for someone else, at the control of someone else, that sense of estrangement is not ideologically neutral. It fosters an anti-government spirit in the electorate that the Koch brothers and their allies would otherwise have to spend billions to instill.

So three cheers for Judge Lewis’ ruling in Florida (which, just Tuesday, the Republican Legislature launched a new effort to undermine)—and three-times-three cheers for the coalition of progressive groups and labor unions who, four years ago, helped get the Fair District amendments passed. And food for thought for progressive organizers and activists around the country to replicate that success in more states over this decade, before the next set of lines is drawn. 2020 will be here sooner than you think.