Last April, Melissa Ortiz, a low-income mother of four, gave testimony to a committee of the California Assembly detailing her life on the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program, or CalWORKs, the state’s welfare program.

“When we first had the twins, the only person in my family getting aid was my oldest son,” she said. “We didn’t have money to buy them car seats to get home [from the hospital]. …We didn’t have money to pay for diapers, wipes, shampoos, and toiletries. … I am here to tell you that I am trying my best to be a great mom. I do not need to be punished for deciding to have children.”

Ortiz was referring to the Maximum Family Grant rule, a provision of CalWORKs that denies assistance to new children in families that received benefits 10 months before the child’s birth. Other states have similar rules, and broadly, they’re called “family caps.” Ortiz and other advocates are lobbying California state lawmakers to repeal these caps, which they argue are harmful and counterproductive. And they are: With four children, Ortiz received just $516 a month in aid from CalWORKs. “I had to go to charities, wait in line, and hope that the charities had diapers that day,” she writes, explaining the impact of family caps on her life. “I am constantly trying to pay just enough to not have [the utilities] shut off.”

For women like Ortiz, new children become a burden to carry—a threat to their livelihoods. But that was always the point. Family caps were designed to make life more difficult for low-income mothers, to thrust them deeper into poverty, and thereby discourage births. Thousands of families occupy the lowest rungs of American society because the state has punished them for having a child it didn’t want them to have. What’s more, in the 16 states where caps exist—including California, Mississippi, Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, and Arizona—the most affected women look like Ortiz, women of color who have been penalized based on a racist stereotype about their worthiness as individuals and fitness as mothers. Indeed, of all of our country’s discriminatory policies, family caps are one of the few that actualizes this prejudice into policy, and in the process, it echoes some the ugliest chapters of our past.

Twenty years ago, House Republicans issued their Contract with America, a concise description of their agenda for the next two years, should they win the majority. Republicans promised procedural reforms—open committee meetings and an audit for fraud—and substantive policies, from crime control to new tax cuts. The third item on their policy list was the Personal Responsibility Act, which would “discourage illegitimacy and teen pregnancy by prohibiting welfare to minor mothers and denying increased [benefits] for additional children while on welfare … to promote individual personal responsibility.”

The language is dry, but the object is clear. If elected to the House majority, Republicans would pass “family caps” and keep your tax dollars out of the hands of irresponsible welfare mothers who had babies for cash. In less inflammatory terms, the family cap was intended to create disincentives for mothers on welfare to have additional children, easing the public burden and providing the poor a path to upward mobility.

Of course, the policy was based on a myth, the idea of the sexually irresponsible “welfare queen.” In 1990, just 10 percent of households that received Aid to Families with Dependent Children—the precursor to today’s federal welfare program—had three or more children (most had two or fewer). Those figures were down from the 1960s, when 32.5 percent of such families had four or more children. In 2013, the Bureau for Labor Statistics noted that “average family size was the same, whether or not a family received assistance.” Public perception notwithstanding, there’s no difference in family size between those that collect welfare and that those that don’t.

Moreover, the notion of family caps presupposes that welfare recipients are somehow gaming their reproductive choices in order to gain the maximum return. It’s an absurd idea, as few people—of any income level—have the necessary time or sophistication to make that kind of calculation, which hinges on a web of federal and state regulations. And it’s even harder to believe that anyone who did would go through the challenge of pregnancy and childbirth for $40 or $50 more a month.

Not that this dissuaded conservative lawmakers. State caps began to appear in the early 1990s, with New Jersey and Arkansas adopting caps in 1992 and 1994, respectively. In 1995, true to their promise, House Republicans passed a welfare reform bill with mandatory family caps. In the Senate, however, Democrats joined with moderate Republicans to defeat the caps over the objection of Majority Leader Bob Dole, who warned, “If we don’t deal with out-of-wedlock births, then we’re really not dealing with welfare reform.” He continued: “The crisis in our country must be faced. Thirty percent of America’s children today are born out of wedlock. … Families must face more directly whether they are ready to care for the children they bring into this world.”

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

In the conference report, House and Senate representatives compromised with mandatory family caps and an opt-out provision, but President Clinton issued a veto, leading to a final bill—signed in August 1996—that omitted a cap requirement, but allowed states to use existing policies, adopt new ones free from federal regulation, or avoid family caps altogether. Of the 16 states that have a family cap policy today, most passed in the aftermath of welfare reform and the introduction of Temporary Aid for Needy Families, the current federal welfare program.

There’s little evidence that family caps work as advertised. What is unquestionably true is that they make poor families poorer. A 2006 report from the Urban Institute found that family caps increase the “deep poverty” rate of single mothers by 12.5 percent, and increase the deep poverty rate of children by 13.1 percent. It’s easy to see how this works. In Maryland, a state without family caps, the average benefit for a single-parent family of three is $574. If, while receiving that benefit, the parent had another child, it would rise to $695, a 17 percent increase. By contrast, in Virginia—where the benefit for a family of three is $389—it would stay the same (as opposed to growing to $451). And when you consider the generally low benefit levels of family cap states—in Georgia, the average monthly benefit for a three-person household is $280, in Mississippi it’s $170—what you have is a recipe for greater poverty.

Given the extent to which welfare families—like their high-income counterparts—have a hard time planning their pregnancies, this is little more than punishment for being poor. After all, we don’t have family caps for the mortgage interest deduction.

And, for all the ways these laws disadvantage poor families, they also fail in their purported mission of reducing family size. Several studies—including a 2001 analysis from the Government Accounting Office—have found no substantial relationship between welfare caps and a reduction in births. “Despite the political attractiveness of caps,“ writes researcher Michael Wiseman in a 2000 study on welfare policy and children, “there is little empirical support for expecting them to do much beyond reducing costs. By far the dominant conclusion of the literature on welfare effects on fertility is that such influences, though present, are small and uncertain.” And while a 2004 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that, in family cap states, “birth rates fell” and “abortion rates rose among high-risk women with at least one previous live birth,” this same pattern happened in states without a family cap, potentially reflecting the degree to which fertility declined among all American women in the later 1990s.

It’s an outrage, but it’s not a surprise. The case for welfare caps wasn’t built from a dispassionate look at outcomes for welfare families. It emerged from our beliefs and stereotypes around the kinds of women who receive government benefits: namely, low-income black women. In the popular imagination, writes legal scholar Laura M. Friedman in a 1995 paper, these women are “thoughtless child-making people” who get pregnant in order to collect money from the government. As such, childbirth by welfare mothers—then, as now—is seen as “undesirable, irresponsible behavior on the premise that people should not have additional children if they cannot afford to support them without governmental aid.”

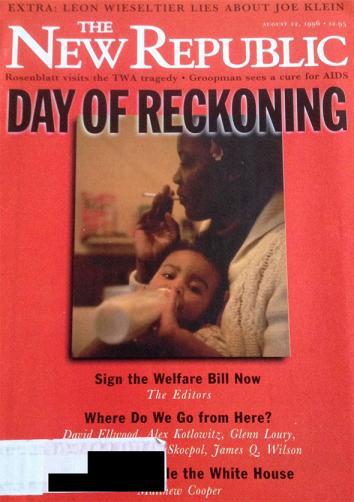

Courtesy of the New Republic.

With his stories of welfare cheats and abusers, Ronald Reagan maybe did more than any single individual to popularize this belief. But the best proof that this stereotype had purchase with nearly all corners of American society comes from the cover of the August 1996 issue of the New Republic. It offers a single image: A poor black woman, feeding a child while holding a cigarette, headlining an editorial titled “Sign the Welfare Bill Now.” The message is impossible to miss: Pass this bill before she breeds again.

Family caps, much more than welfare reform itself, are an extension of a racist stereotype. By ending the “incentive” of reproduction, goes the argument, caps would arrest the spiral of moral decline and pathology in poor black communities, and end the crime and poverty that presumably flows from black single motherhood.

As then-Oklahoma Sen. Don Nickles said in 1995, “Illegitimacy has been exploding in this country. As a result, we have increased crime, we have increased welfare, and we need to break that cycle.” Or, as conservative scholar Robert Rector put in more gentle terms, “A ‘reform’ of the federal welfare system which fails to send a clear moral signal, which remains agnostic on the question of illegitimacy, and which simply allows states to ‘do their own thing’ with federal taxpayers’ funds—or do nothing—would be a disaster.”

It’s hard to escape the eugenic tint of these arguments. Indeed, when you situate family caps in the broad history of American policy and reproductive rights, it’s easy to see the connective tissue between eugenics and benefit cuts to stop “illegitimacy.”

At the turn of the 19th century, several states—Michigan, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Washington, and California—all passed or attempted to pass forced sterilization laws. In 1929, North Carolina passed “An Act to Provide for the Sterilization of the Mentally Defective and Feeble-Minded Inmates of Charitable and Penal Institutions of the State of North Carolina,” which allowed sterilization for both “improvement of the mental, moral, or physical condition of any inmate” or “the public good.” Between 1929 and 1935, under the act, North Carolina sterilized 223 people. In 1935, following a challenge from the state supreme court, North Carolina established the Eugenics Board to provide due process for individuals condemned to sterilization.

Initially, the targets of sterilization were inmates and the mentally disabled. But over time policymakers and bureaucrats moved to the physically disabled and other groups. Wallace Kuralt served as welfare director in Mecklenberg County, North Carolina, from 1945 to 1972. During that time, Kuralt expanded the sterilization program to include the poor and destitute, with a particular focus on black Americans. In 1960, black Americans were 25 percent of the population in Mecklenberg. But between 1955 and 1966, noted the Charlotte Observer in a 2011 piece investigating Kuralt’s work, they made up more than 80 percent of those sterilized at the request of the Welfare Department.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

“When we stop to reflect upon the thousands of physical, mental, and social misfits in our midst,” wrote Kuralt in 1964, “the thousands of families which are too large for the family to support, the one-tenth of our children born to an unmarried mother, the hoard of children rejected by parents, is there any doubt that health, welfare, and education agencies need to redouble their efforts to prevent these conditions which are so costly to society?” Sterilization, he believed, would save tax dollars by reducing poverty among the “low mentality-low income families, which tend to produce the largest number of children.” Or, as he wrote in an unsigned editorial the same year, “[A]t the bottom of many welfare problems is the illegitimate child, the unwanted child in his most extreme form.”

Proponents of family caps in the 1990s didn’t claim that welfare families were irredeemably “unfit” and “feeble,” nor did they profess to see poverty as a product of innate deficiency. But the preoccupation with the reproductive behavior of the poor, the unsubstantiated belief that they’re a drain on public coffers, the focus on black American women, the cries against “illegitimacy,” and the calls for action are all reminiscent of the not-too-distant past.

Consider that the only exception to the family cap in the CalWORKs program is for births resulting from a contraception failure under an approved method: A contraceptive shot, an intrauterine device, or sterilization.* Put another way, women in CalWORKs have to choose between long-term or permanent contraception or risk becoming pregnant with a child who won’t receive state aid. California, it should be said, also has a long and dark legacy of eugenics—more Americans were forcibly sterilized there than in any other state.

Some states have ended the failed family caps experiment. In the last decade, Maryland, Minnesota, Illinois, Wyoming, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Kansas have repealed their caps, while other states have modified or revised their programs. And in January of this year, California state Sen. Holly Mitchell introduced a bill to repeal the state’s Maximum Family Grant. With wide support from groups like the ACLU, the Catholic Conference, and Planned Parenthood, it promised to end this discriminatory regulation and commit California to $200 million in additional benefits for poor families with children.

After passing the Senate Human Services Committee on a narrow 3–2 vote, it made its way to the Appropriations Committee, where it died, on account of its high cost. If it had been passed and signed into law, it would have reduced childhood poverty in the state by up to 7.4 percent. Supporters are crushed, but remain dogged. “The reproductive justice and anti-poverty advocates who have been working diligently to repeal this harmful and ineffective rule are sorely disappointed and surprised the bill didn’t make it out of committee, but we are not giving up,” said Shanelle Matthews, communications strategist for the ACLU of Northern California, in an email.

Given its size and influence, an end to family caps in California might prompt other states to re-evaluate their policies. And if nothing else, it would do a lot of good. As of April, nearly 250,000 families in the state are still subject to family caps. “One in six California children are living in poverty or something called deep poverty,” said Sen. Mitchell in a recent speech touting her bill, “Fifteen red states across the country have reversed their maximum family grant policy.” It’s time all states do the same.

Correction, June 18, 2014: This article originally misstated that NuvaRing is an intrauterine contraceptive. It is not. The reference has been removed. (Return.)