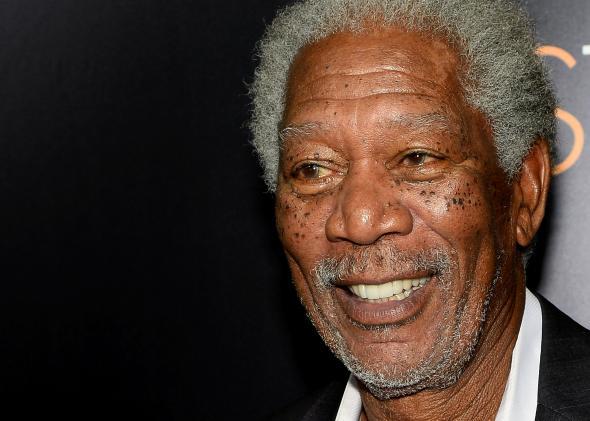

Morgan Freeman has played the omnipotent old man for so long that I assume he knows everything, or, at least, has sensible opinions on most things. Of course, that’s nonsense. Morgan Freeman is just an actor, which is to say, he’s just a person. And, it turns out, he’s a person with dubious views on income inequality.

On Tuesday, in an interview with CNN’s Don Lemon, he touched on the recent political attention to inequality. First, he said, he thinks it’s a “great idea” that President Obama has focused on inequality. “We have a much more vibrant society when we don’t have such a vast chasm between the haves and the have-nots,” he said. He continued, “Without a middle class, you’re not going to have consumers.”

At this point, Lemon asked a follow-up question: Do you think race has anything to do with inequality? “Today?” Freeman answered. “No. … You and I, we’re proof.”

“Why would race have anything to do with it?” he added. “Put your mind to what you want to do and go for that. It’s kind of like religion to me—it’s a good excuse for not getting there.”

After a few more questions from Lemon, Freeman finished with a final thought. “Making [race] a bigger issue than it needs to be is the problem here.”

Again, coming from Freeman—with his authoritative voice—this sounds correct. But it’s painfully wrong. Yes, the gap between rich and poor is wider than it’s been since before the Great Depression, and yes, the top 1 percent of all households command more than a third of U.S. wealth. At the same time, there are huge racial disparities within the overall wealth gap. In a recent study, researchers at the Center for Global Policy Solutions found that “Whites have a median net worth over 15 times that of Blacks ($111,740 vs. $7,113), and over 13 times that of Latinos ($111,740 vs. $8,113).”

It’s true that there’s always been severe gaps between black and white Americans. Even during the economic expansion of the 1990s, joblessness among blacks was twice as high as it was among whites.

Still, after five years of recession, mass unemployment, and sluggish growth, the wealth gap between blacks and whites is wider now than it’s ever been. According to the Pew Research Center, the difference in wealth between black and white households increased from $75,224 in 1984 to $84,959 in 2011. And a 2012 census analysis found that the gap nearly doubled during the recession, with white households at 22 times the wealth of their black counterparts. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the housing collapse all but destroyed the wealth accumulated by black Americans over the last five decades.

Notwithstanding Freeman, there’s no understanding income inequality—or the disparities in criminal justice, education, health care, and unemployment—without a firm grasp of race, or rather, the economic consequences of past and current racism. Of course, we can forgive Freeman for his naive belief that individual achievement is evidence of a level racial playing field. It’s harder to excuse President Obama, who—in a speech on inequality last year—disavowed the idea that race is an especially salient dimension of disadvantage.

“The opportunity gap in America is now as much about class as it is about race,” he said. “So if we’re going to take on growing inequality and try to improve upward mobility for all people, we’ve got to move beyond the false notion that this is an issue exclusively of minority concern.”

But this is belied by everything we know about class status for blacks and whites. Even when they earn middle-class incomes, black Americans live in dramatically poorer neighborhoods than their white counterparts. And in turn, downward mobility is a greater risk for middle-class blacks in a way that isn’t true for whites of the same station. To return to a point I’ve made before, the economic difference in upbringing between most black children and most white children is so great as to escape comparison. Or, as sociologist Mary Pattillo writes, “even the most affluent blacks are not able to escape from crime, for they reside in communities as crime-prone as those housing the poorest whites.”

My hunch is that Obama knows this, hence a program like My Brother’s Keeper, which puts its focus on young black men. Indeed, in his speech announcing the initiative, he said as much. “[T]he plain fact is there are some Americans who, in the aggregate, are consistently doing worse in our society—groups that have had the odds stacked against them in unique ways that require unique solutions.” He continued, “[B]y almost every measure, the group that is facing some of the most severe challenges in the 21st century in this country are boys and young men of color.”

I would amend this to include young women of color, but otherwise, he’s right. And, as we craft policy to ameliorate these problems, we should keep his point in mind. If the goal is success, then the fight against inequality—and more broadly, the fight for opportunity—has to consider race. There’s no other choice—despite what some actors will tell you.