Officially, the Emancipation Proclamation freed “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State” where the residents were “in rebellion against the United States.” In practice, it applied only to those slaves who lived near Union lines, where they could make an easy escape or take advantage of the Northern advance.

News of emancipation would move slowly, which would be compounded by the mass migration of slave owners, who fled their holdings in Louisiana and Mississippi—slaves in tow—following the Union victories at New Orleans in 1862 and Vicksburg in the spring and summer of 1863. Tens of thousands of slaves arrived in Texas, joining the hundreds of thousands in the interior of the state, where they were isolated from most fighting and any news of the war. Indeed, Union attempts to occupy Texas were limited to the coastlines—far from the densest slave populations—or repelled before they had a chance to succeed.

As such, for the next two years, slaves and slave holders lived at a far remove from the events of the eastern United States, including the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia in April 1865. Yes, it ended the war, but it didn’t end the conflict, as fighting continued on the far borders of the Confederacy. And so, when Gen. Gordon Granger entered Galveston, Texas, on June 19 to lead the Union occupation force, he wasn’t just faced with Confederate remnants (the Army of the Trans-Mississippi, for example, had surrendered only a month prior); he had to deal with ongoing slavery in defiance of the Emancipation Proclamation.

To fix the situation, he issued an order:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

This proclamation would form the basis for June the Nineteenth or “Juneteenth,” a holiday celebrating the announcement of the end of slavery in Texas.

I say announcement because it would be a stretch to say this freed the slaves of Texas. There, as elsewhere in the South, attempts to act on this freedom were met with violence from former slave owners and other angry whites. “There is much evidence to suggest that southern whites—especially Confederate parolees—perpetrated more acts of violence against newly freed bondspeople in Texas than in other states,” writes historian Elizabeth Hayes Turner in an essay titled “Juneteenth: Emancipation and Memory.” “Between the Neches and Sabine rivers and north to Henderson,” she continues, “reports showed that blacks continued in a form of slavery, intimidated by former Confederate soldiers still in uniform and bearing arms.” Murder, lynching, and harassment were common. “You could see lots of Negroes hanging from trees in Sabine bottom right after freedom,” reported one freed slave, “They would catch them swimming across Sabine River and shoot them.”

But neither violence nor the sheer size of Texas could stop emancipation from rolling across the landscape. And as it did, freed slaves began to commemorate and celebrate the event, both as an occasion for jubilee and as an act of defiance toward unreconstructed Confederates and other whites who maintained their grip on power in the state.

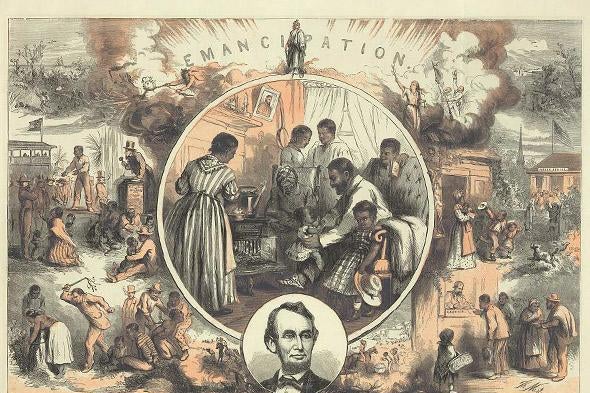

The first public Juneteenth events occurred in 1866, preceding any similar commemoration of the Confederacy legacy in Texas. At these events, former slaves read the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation—subversively honoring Abraham Lincoln as the Great Emancipator at a time when white Texans saw the slain president as the destroyer of Southern “freedom”—sang spirituals, held games, and celebrated freedom.

These celebrations would continue throughout the 19th century—growing in size and prominence—until the advent of Jim Crow and the aggressive repression of the early 20th century, when blacks were fully disenfranchised and outside the protection of law, vulnerable to the depredations of terrorists and lynch mobs. Put another way, it’s difficult to celebrate freedom when your life is defined by oppression on all sides. Still, the holiday remained in the civic life of black Texans, and began to expand beyond the state with the Great Migration of blacks from the South. As Isabelle Wilkerson writes in The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, “The people from Texas took Juneteenth Day to Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and other places they went.”

With the growth of the civil rights movement in the middle of the 20th century, Juneteenth began to reclaim its space as a central holiday on the black American calendar. It experienced a resurgence in 1968, following the “Poor Peoples March” to Washington D.C., which coincided with the holiday. Attendees from the event brought the celebration back to their homes, creating new traditions in cities and towns across the country. Juneteenth was made a Texas state holiday in 1980, and in 1997, Congress recognized June 19 as “Juneteenth Independence Day,” after pressure from a collection of groups like the National Association of Juneteenth Lineage and National Juneteenth Celebration Foundation.

Thursday marks the 148th anniversary of the first Juneteenth. For now, it’s a niche holiday, celebrated by black Americans and a handful of others who know and understand the occasion. But it deserves wider reach. Indeed, I think we should add it to the calendar of official federal holidays.

Insofar that modern Americans celebrate the past, it’s to honor the sacrifices of the Greatest Generation or to celebrate the vision of the Founders. Both periods are worthy of the attention. But I think we owe more to emancipation and the Civil War. If we inaugurated freedom with our nation’s founding and defended it with World War II, we actualized it with the Civil War. Indeed, our struggle against slave power marks the real beginning of our commitment to liberty and equality, in word, if not always in deed.

Put another way, Juneteenth isn’t just a celebration of emancipation, it’s a celebration of that commitment. And, far more than our Independence Day, it belongs to all Americans.