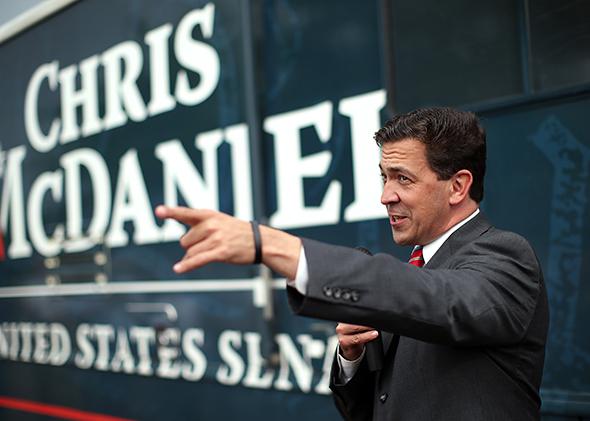

Three days after his loss in the Mississippi Republican Senate run-off, state Sen. Chris McDaniel sounds like a bitter Scooby Doo villain. “They used everything from the race card to food stamps to saying I would shut down public education,” he said in an interview with conservative TV personality Sean Hannity. “I’ve fought for this [Republican Party] all my life, but they abandoned us, made fun of us and ridiculed us and brought in 35,000 Democrats to beat us.”

In other words, McDaniel is saying, I would have won if it wasn’t for you meddling liberals.

Of course, we should be clear. Because there is no party registration in Mississippi, there’s no way to know the affiliation of the people who voted in Tuesday’s run-off. McDaniel complains that “35,000 Democrats crossed over,” but he can’t know for sure. Instead, he’s made an assumption: These black voters are Democrats, and their votes are illegitimate. “There is something a bit strange, there is something a bit unusual, about a Republican primary that’s decided by liberal Democrats,” he said after the election.

He’s likely right that the voters were Democrats—Mississippi’s voting is entirely polarized along racial lines—but given the open primary he has no room for complaint. There’s nothing fraudulent about Sen. Thad Cochran’s appeal to black Mississippians, nor is there anything irregular about their participation in a Republican primary that will determine the state’s representation in the U.S. Senate. As Sen. Roger Wicker, the junior senator from the state, said to reporters on Wednesday, “Broadening the base of the party? Asking more Mississippians to participate in the ballot that’s going to determine the next senator? No, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.”

Obviously, McDaniel does. And in holding that view—whether he knows it or not—he channels a long history of similar complaints. For as long as blacks have been able to vote, there have been politicians who sought their support. And for just as long, there have been critics who called it unfair.

“What think you of the Grants and Colfaxes?” asked former Confederate Major Gen. Howell Cobb in an 1868 speech to Democrats opposing Ulysses Grant for president. “Of the Thad Stevenses? The Sumners and Wilsons of the North … who wrote it upon their platform: ‘The people of the South, you must submit to negro suffrage, you must submit to negro supremacy; but for our own people we reserve the old landmarks of the Constitution.’ ”

Cobb, who died before the election, had laid down the core argument of the contest. Who is America for, Democrats asked, the white man or the black? Their answer was simple: America was a white man’s country, and if elected, the Democratic ticket—led by Horatio Seymour and Frank Blair—would oppose the Radical Republicans who sought “military despotism and negro supremacy.” As Blair declared in a September speech while touring towns along the Pacific Railroad, “The great masses of this mighty Republic have no affinity with the negro. The right of elective franchise is for the white man alone.”

The Republican Party disagreed, and—campaigning for its nominee, Gen. Grant—it appealed to pro-Union Northern whites and newly enfranchised Southern blacks (who had the right to vote under the military governments of the former Confederacy). “During the 1868 campaign,” writes historian Eric Foner in Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, “Yazoo County, Mississippi, whites found their homes invaded by buttons depicting General Grant, defiantly worn on the clothing of black maids and cooks.”

The result was a win for Grant, who entered the White House on the strength of the first truly biracial political coalition in American history. Having lost the white vote, Grant owed his slim majority of roughly 300,000 to the more than 700,000 blacks who supported his ticket.

That didn’t escape his Democratic opponents, who accused Republicans of fraud and denounced Grant as an usurper. “It is now ascertained beyond a shadow of a doubt that the Jacobin candidates were elevated to office against the wishes of a decided majority of the white voters of the country,” wrote one angry voter in a Washington territory newspaper, “If we take into calculation the white men denied a ballot by the disenfranchisement of the states of Virginia, Mississippi, and Texas … the radical ticket was successful against a majority of more than one million white men.”

This notion, that it was wrong to appeal to blacks and illegitimate to win with their votes, would dog President Grant throughout his first term, and into the 1872 election, which he won—once again—on the strength of black support.

By the 1876 presidential election, white supremacist terrorism had driven countless black Americans from the polls, and by the 1880 contest, black suffrage was on the wane—Southern states had begun the long process of disenfranchisement, using law and violence to keep blacks out of politics. For more than a half-century, black Americans were absent from mainstream politics, the victims of Jim Crow oppression and national neglect. Still, the idea of illegitimate black votes lived on.

After the Texas Populist movement won influence with multiracial coalitions of poor white and black voters, Democratic leaders responded with mechanisms to ensure white hegemony, like the “white primary.” The goal was simple: to keep blacks out of the political process and to stigmatize whites who tried to bring them in.

None of this is to say McDaniel is the same as these people in the past. But history often rhymes, and we see elements of old arguments in the controversy over Cochran’s win. Indeed, we saw them during the 2008 Democratic primary, when Hillary Clinton dismissed the then-Illinois senator’s support from black voters, calling it narrow:

“I have a much broader base to build a winning coalition on,” she said in an interview with USA Today. As evidence, Clinton cited an Associated Press article “that found how Sen. Obama’s support among working, hard-working Americans, white Americans, is weakening again, and how whites in both states who had not completed college were supporting me.”

Likewise, Obama’s 2008 presidential win was followed by conservative hysteria over ACORN and the New Black Panthers—described as vehicles for mass voter fraud—as well as skepticism of his standing with the public. “[T]he president and some of his policies are significantly less popular with white Americans than with black Americans,” wrote Byron York for the Washington Examiner in 2009, “and his sky-high ratings among African-Americans make some of his positions appear a bit more popular overall than they actually are.” In other words, if you stick with the voters who count—white ones—then Obama isn’t as popular as he looks.

Yes, in some sense, these are all the complaints of sore losers. But they tell us something important about American life: When it comes to race and politics, there’s almost nothing new under the sun.