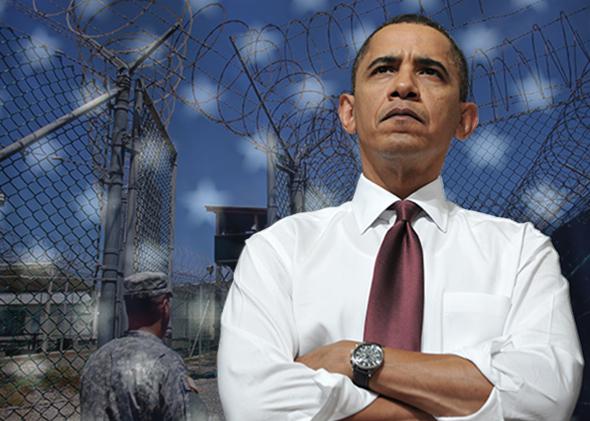

I believed Barack Obama when he promised to close Guantánamo. It sounds so naïve. But in the days after his first inauguration, I didn’t think twice about betting Ann Althouse that our new president would keep his promise to close the offshore military prison within a year.

Of course, Obama caved and Althouse won. Congress resisted both releasing the detainees—so-called enemy combatants whom the United States scooped up in Pakistan and Afghanistan in the wake of 9/11—and moving them to a military brig on U.S. soil. After Attorney General Eric Holder lost his bid to try 9/11 planner Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in New York, Obama slunk away. Instead of trying the Gitmo detainees in federal court, his administration has made do with sputtering proceedings before military tribunals, which afford fewer procedural protections than regular court, and offer a window to admitting evidence gathered by coercion. A desperate hunger strike in the prison has become a macabre spectacle, with force-feedings that inflict “unnecessary pain” because of Department of Defense “intransigence,” according to an anguished federal judge, yet must go on lest determined, suffering detainees die. Instead of releasing 78 men cleared for transfer by his own task force, Obama has kept them at Gitmo even though most have had this limbo status since January 2010.

But now, in exchange for the freedom of Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, the president has released five prisoners who sound dangerous. They were not cleared for transfer. They had mid- or high-level roles in the Taliban in Afghanistan. These are not the detainees who wound up in Gitmo because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, or because the U.S. was offering $5,000 bounties to the Pakistanis for turning in anyone who could be passed off as a suspected terrorist.

According to CNN, one of the five, Mullah Mohammad Fazl, “commanded the main force fighting the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance in 2001, and served as chief of army staff under the Taliban regime. He has been accused of war crimes during Afghanistan’s civil war in the 1990s.” It does not comfort me that Fazl and the others are Taliban rather than al-Qaida. Or that they have to spend a year in Qatar before they can go home. What are the chances these men will end up joining up with extremists, or returning to Afghanistan as American troops are pulling out and adding to the pile of woes that are surely in store there? The odds seem high. That’s the grim bet I’d take today. After all this time, it turns out that the president is willing to let go detainees who pose a risk—even as he holds on to dozens who probably don’t.

Another fail on Obama’s part: He didn’t tell Congress about the prisoner release 30 days ahead of time, as a recent federal law requires. To justify this omission, the administration has invoked Obama’s signing statement, which he added to the law for “certain circumstances,” like negotiating over detainee transfers, in which it “would violate constitutional separation of powers principles” to consult Congress. The idea is that if Congress had been notified 30 days in advance, the negotiations over the trade could have been jeopardized by a leak, ruining our chance of rescuing Bergdahl. The president’s lawyers think that for Congress to require advance notice in this scenario is to intrude on the president’s war-making powers. And so Obama took it upon himself to create his own emergency exception.

Obama called signing statements an “abuse” when George W. Bush used them to “advance sweeping theories of executive power,” as Charles Savage puts it in the New York Times. Now he’s using signing statements to make his own power grab. It’s another version of Obama’s disappointing switch on surveillance, from the candidate who said “no more illegal wiretapping of American citizens” to the president who says that the National Security Agency’s mass data sweeps are legal because they were presented to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court for a rubber stamp.

Presidents tend toward overreach. Congress isn’t good at pushing back. Each president who usurps more authority for his office makes it easier for the next one to do more of the same. This will be a part of Obama’s legacy that darkens over time.

But it’s Guantánamo that looms largest and blackest now. I don’t know what to think about the contested accusations that Bergdahl’s decision to walk away from his unit in Afghanistan five years ago cost other Americans their lives, or how to feel about whether “leave no man behind” should extend to deserters. I’m glad United States policy isn’t driven by obsession over rescuing prisoners of war; I’m also glad Bergdahl is home. In five years of captivity with the Taliban, he surely suffered enough. But what about the suffering of Jihad Ahmed Mujstafa Diyab, the Syrian held in Guantánamo for 12 years without a trial, a man on the 2010 list of recommended transfers, who is being strapped against his will into a chair so a feeding tube can be forced into his nose and down his throat?

The government doesn’t want to send Diyab back to Syria in the middle of the war there. Uruguay has offered to take him and five other detainees. Yet they’re still in Gitmo. As Andy Worthington writes at PolicyMic, for the 78 men cleared for transfer who remain imprisoned, “the release of the five Taliban prisoners is unlikely to cause anything but despair.”

Last month the president said on NPR, as he has said before, “We cannot in good conscience maintain a system of indefinite detention in which individuals who have not been tried and convicted are held permanently in this legal limbo outside of this country.” But that is exactly the system he is maintaining. Because he can. The Supreme Court lost interest in Guantánamo years ago, turning down appeal after appeal since 2008. For Obama, the calculation can only be this: In office, it is simply not worth the political price to stand up for miserable men in orange jumpsuits with long foreign names. And so even as he inveighs against the “system,” other than the five Taliban traded for Bergdahl, only one Guantánamo detainee has been released this year.

If I’m counting right, there are 149 men left in the prison. How many of them will die there? I’m not talking now about death by hunger strike. I’m talking about death by old age. That is where indefinite detention ends. Bush created this monster. But it will haunt Obama, too, if he doesn’t slay it.