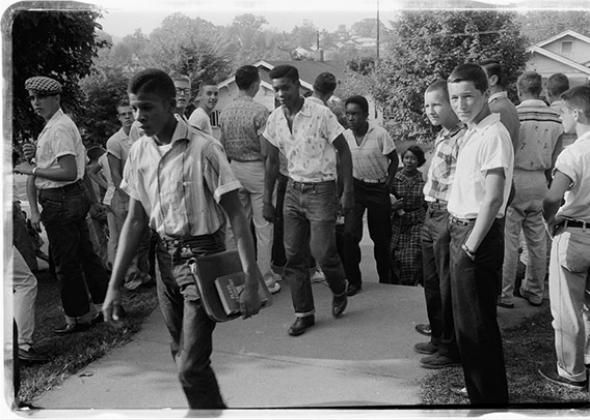

With “The Case for Reparations,” Ta-Nehisi Coates of the Atlantic sets slavery aside to focus on the long plunder of the 20th century, in which whites used coercion, violence, and government to exclude blacks from the bounty of American prosperity. The civil rights revolution of the 1960s was vital, but it wasn’t a panacea, and the problems of today—from the racial wealth gap to the crumbling ghettos of the Midwest—stem from the racist policies of our recent past. Or, as Coates puts it, “White supremacy is … a force so fundamental to America that it is difficult to imagine the country without it.”

This is more than rhetoric. Black families paid taxes and black soldiers fought for democracy in Europe and the Pacific, but—from low-interest home loans to money for education—they were barred from the benefits of the G.I. Bill. Indeed, the same federal dollars that built the suburbs were used to keep blacks out of them. It was the federal government that “pioneered the practice of redlining,” writes Coates, “selectively granting loans and insisting that any property it insured be covered by a restrictive covenant—a clause in the deed forbidding the sale of the property to anyone other than whites. Millions of dollars flowed from tax coffers into segregated white neighborhoods.” At the same time, “legislatures, mayors, civic associations, banks, and citizens all colluded to pin black people into ghettos, where they were overcrowded, overcharged, and undereducated.”

The case for reparations, in short, is straightforward. As a matter of public policy, America stole wealth from black people, denied them a shot at prosperity, and deprived them of equal citizenship.

And that’s just the 20th century. If you go beyond that—to include all stolen income from the revolution to secession—the balance falls deep into the red. In 1860, translated to today’s terms, slaves represented a staggering $10 trillion in wealth, an incredible sum. If you include compound interest—to represent the compounding plunder of the next century—you are left with an implausibly large amount of money.

Wisely, Coates doesn’t try to build a proposal for reparations. At most, he endorses a bill—HR 40—that would authorize a government study of reparations. Instead, his goal is to demonstrate the recent origins of racial inequality, the role of the federal government, the role of private actors, and the extent to which the nation—as a whole—is implicated. Even if your Irish immigrant grandparents never owned slaves, or even lived around black people, they still reaped the fruits of state-sanctioned—and state-directed—theft, through cheap loans, cheap education, and an unequal playing field.

If anything, what Coates wants is truth and reconciliation for white supremacy—a national reckoning with our history. As he writes, “More important than any single check cut to any African American, the payment of reparations would represent America’s maturation out of the childhood myth of its innocence into a wisdom worthy of its founders.”

Still, even if “no number can fully capture the multi-century plunder of black people in America,” there’s still value in imagining a concrete scheme for reparations, if only to have a sense of the bills we owe. And so, how would we accomplish the task? Would you attempt a massive transfer of wealth? Or would you try to compensate black communities with targeted policies?

The “wealth option,” accomplished by cash payments, is what we tend to think when we hear “reparations.” In this scenario, the federal government would mail checks to individuals, either in a lump sum or spread out over time. There are a few, immediate concerns with this notion. First, who is eligible? Given the pervasiveness of anti-black prejudice, should it go to all black Americans—who, regardless of origin, deal with the burden of white supremacy—or should it go to the descendants of slaves, who share a unique disadvantage? And how do we determine lineage? Through self-reporting? Through a comprehensive census of black Americans? Genealogical records for slaves are so scarce that any method of selection will come with the risk of fraud, since for most, we can’t confirm with absolute certainty that a given person is a descendant of slaves.

And even if we could agree on recipients, how much should individuals receive? A uniform sum or an amount based on your heritage, i.e., the more enslaved ancestors you have, the bigger your payment?

Even with all of those questions, however, there’s a lot to recommend when it comes to cash benefits. For starters, it empowers individuals, families, and communities. They know what they need, and we should trust them to figure out their own interests over the long term. Yes, a cash scheme could never be fully fair, but that’s not the point; what we want is to heal injury and balance accounts, and on that score, it could work.

On the other end is the policy approach. Instead of cash, the federal government would implement an agenda to tackle racial inequality at its roots. This agenda would focus on major areas of concern: housing, criminal justice, education, and income inequality. As for the policies themselves, they don’t require a ton of imagination. To break the ghettos and reduce the hyper-segregation of black life, the federal government would aggressively enforce the Fair Housing Act, with attacks on housing and lending discrimination, and punishment for communities that exclude low-income residents with exclusionary zoning.

What’s more, it would provide vouchers for those who want to move, subsidized mortgages for those who want to own, and huge investments in transportation infrastructure, to break urban and rural isolation and connect low-income blacks to jobs in wealthier, whiter areas.

On the education front, state governments could end education budgets based on local property taxes—which disadvantage poor communities and disproportionately hurt blacks—and the federal government could invest in school reconstruction, modernization, and vouchers—for parents who want their children in private schools—in addition to higher education subsidies for black Americans. These “in-kind” benefits have the virtue of freeing up disposable income, thus acting as de facto cash payments.

It almost goes without saying that this move for policy reparations would include an end to the war on drugs, an end to mass incarceration, and a national re-evaluation of police procedures to reduce racial profiling. And, looking forward, it could include progressive “baby bonds”—federally managed investment accounts with modest annual growth rates. At $60 billion a year, according to one proposal, this would help ameliorate wealth inequality for future generations.

There are more policies along these lines, no doubt. The advantage, for most of these, is that they are both universal and hugely beneficial to black Americans.

Of course, however you designed a reparations scheme, it would be incredibly unpopular. Between our racialized disdain for the “undeserving” and general distaste for intrusive government, nothing on this scale could get off the ground. Even if it could, there’s an excellent chance the courts would kill it.

And ultimately, as Coates writes, the money isn’t important. What’s critical is that we reckon with our national crimes against black Americans, to say nothing of Native Americans and other minority groups. We must wrestle with our history, lest we ignore the “certain sins of the future”—or worse—the sins of our present.