Comedy Central’s Key & Peele, a sketch comedy show from Keegan Michael Key and Jordan Peele, has a great recurring bit that debuted during the 2012 presidential election. In it, President Obama (played by Peele) responds to his more populist liberal critics with a new hire, Luther, his “anger translator” (played by Key).

When Obama says, “I know a lot of folks say I haven’t done a good job at communicating my accomplishments to the public,” Luther translates with “Because y’all don’t listen!” And when Obama says he wants Republicans to know his “intentions are coming from the right place,” Luther gives the real message, “They’re coming from Hawaii, which is where I’m from, which is in the United States of America, y’all. This is ridiculous. I have a birth certificate!”

The parallel isn’t great—there’s no visible anger, for one—but I can’t help but think of this skit when I see Barack Obama, Attorney General Eric Holder, and their rhetoric on race and racism.

Obama has said less on race than any other president, and when he does speak, he tends to aim for broad inclusivity. In his 2008 Philadelphia speech, given in the wake of the Jeremiah Wright controversy, he analogized the “anger within the black community” to the “resentments” in “segments of white community,” arguing against both as counterproductive, while urging listeners to recognize that they are “grounded in legitimate concerns.” Likewise, in his remarks on the George Zimmerman verdict last year, he challenged Americans to ask themselves about their own lives. “[A]m I wringing as much bias out of myself as I can? Am I judging people as much as I can based on not the color of their skin, but the content of their character?” he said.

In each case, he strives to speak to all Americans, reflecting politics—he doesn’t want to alienate white people—as well as his own life and experiences. At the same time, in all of remarks on race, he leaves hints of a deeper, less conciliatory critique. His Philadelphia speech, for instance, includes a small section on the persistence and power of institutional racism:

Legalized discrimination—where blacks were prevented, often through violence, from owning property, or loans were not granted to African-American business owners, or black homeowners could not access FHA mortgages, or blacks were excluded from unions, or the police force, or fire departments—meant that black families could not amass any meaningful wealth to bequeath to future generations.

And his remarks on Zimmerman began with a note on the reality of anti-black prejudice in modern America:

There are probably very few African-American men who haven’t had the experience of walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of cars. That happens to me—at least before I was a senator. There are very few African-Americans who haven’t had the experience of getting on an elevator and a woman clutching her purse nervously and holding her breath until she had a chance to get off. That happens often.

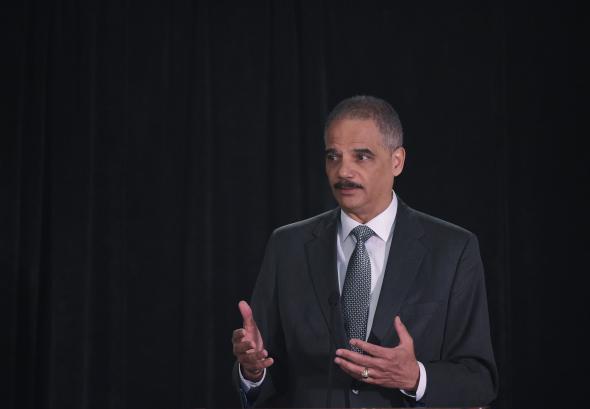

Insofar that this is subtext, it becomes text for Eric Holder. When he speaks on race and racism, he doesn’t try to mollify the audience. Instead, he’s blunt. “Though this nation has proudly thought of itself as an ethnic melting pot, in things racial we have always been and continue to be, in too many ways, essentially a nation of cowards,” said Holder in 2009. He continued: “On Saturdays and Sundays, America in the year 2009 does not, in some ways, differ significantly from the country that existed some 50 years ago.”

Where Obama floats an idea, Holder issues an indictment. Americans aren’t as tolerant as they imagine, he says, and they certainly don’t want to talk about it. What’s more, in Holder’s estimation, they’d rather focus on the cartoonish bigotry of a Donald Sterling than the deep inequities of our society.

It’s to that end that—in a commencement address on Saturday—Holder stressed the “subtle” threats to “equal opportunity” that “no longer reside in overly discriminatory statutes” or take the form of “outright bigotry.”

In his speech to graduates at Morgan State University, a historically black college in Baltimore, Maryland, the attorney general said the threat comes from ostensibly “colorblind” policy that “impedes equal opportunity in fact, if not in form.”

For Holder, there’s renewed school segregation and “zero-tolerance school discipline practices that … affect black males at a rate three times higher than their white peers.” Likewise, there’s disproportionate sentencing in the criminal justice system—“African-American men have received sentences that are nearly 20 percent longer than those imposed on white males convicted of similar crimes”—and “attempts to curb an epidemic of voter fraud” that “disproportionately disenfranchise African-Americans, Hispanics, other communities of color and vulnerable populations such as the elderly.”

In short, Holder argued, “these policies that disenfranchise specific groups are more pernicious than hateful rants.” Indeed, it’s here he took aim at conservatives who argue for colorblindness. “Chief Justice John Roberts has argued that the path to ending racial discrimination is to give less consideration to the issue of race altogether,” he said, in a direct rebuke, “This presupposes that racial discrimination is at a sufficiently low ebb that it doesn’t need to be actively confronted.” The truth is just the reverse. “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race,” he said in a twist on Roberts’ famous phrase “is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race.”

To be clear, this address wasn’t a barnstormer. But Holder speaks forcefully on institutional and systemic racism in a way we don’t normally hear from Obama but that compliments his rhetoric.

As the Obama era ends, however, that might be changing. Last month, on the anniversary of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Obama spoke to the National Action Network, where he attacked voter ID laws as unfair and discriminatory. “America did not stand up and did not march and did not sacrifice to gain the right to vote for themselves and for others only to see it denied to their kids and their grandchildren,” he said. And in an interview with David Remnick of The New Yorker, published in January, he was forthright about the role his race played in some of the opposition to his presidency. “There’s no doubt that there’s some folks who just really dislike me because they don’t like the idea of a black president,” he said.

Soon, Obama will leave office and join the rarefied world of the post-presidency. With politics out of the way, and the new freedom that brings, there’s a chance he becomes his own “Luther” on race and racism, free to say what he thinks.