Over several weeks in 2012, an animal rights activist secretly filmed workers at an Idaho dairy farm kicking and punching cows in the head, jumping up and down on their backs, sexually abusing one, and dragging another behind a tractor by its neck. The Mercy for Animals-made video—one of roughly 80 that activists say they’ve recorded over the past decade—prompted the owners of Bettencourt Dairies to fire five workers and install cameras in their barns to prevent future abuses. A police investigation, meanwhile, ended with three of the fired employees charged with animal cruelty. It was a clear victory for those groups that have made it their mission to expose animal cruelty and criminal wrongdoing on modern American farms.

It will also be their last, if the agriculture industry and its allies in state government have their way.

Earlier this year, Idaho became at least the seventh state to pass a law aimed specifically at thwarting such undercover investigations, and roughly a dozen similar bills are currently winding their way through statehouses around the country. While the specifics vary, so-called ag-gag laws generally make it illegal to covertly record animal abuse on farms, or to lie about any ties to animal rights groups or news organizations when applying for a farm job. Idaho’s law is the strictest of those currently on the books. It threatens muckrakers with up to a year in jail and fines up to $5,000—a sentence, it should be noted, that’s the same as what someone convicted of animal abuse faces.

The laws specifically target animal rights groups like the Humane Society of the United States, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, and similar organizations that have increasingly turned to clandestine video in their battle with Big Ag. But the way many of the laws are tailored, they also could ensnare journalists, whistleblowers, and even unions in their legal net, in the process raising serious concerns about the legal impact on everything from free speech to food safety. A wide-ranging coalition of organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union and the Center for Food Safety, has joined animal rights groups in challenging the Idaho law, along with a similar one in Utah, in federal court. The lawsuits also have the backing of the Government Accountability Project, the AFL-CIO, and a host of media organizations, including NPR.

“They can dress these laws up however they want, but ultimately the rationale here is pretty clearly self-interest on the part of the industry,” says Michael McFadden, the general counsel at Farm Forward, an advocacy group that’s leading the charge against such laws. The industry and their statehouse allies don’t necessarily disagree. State Sen. Jim Patrick, a lead sponsor of the Idaho legislation and a farmer himself, explained the rationale behind his bill: “It’s not designed to cover up animal cruelty, but we have to defend ourselves.”

The way Patrick and his like-minded colleagues see things, farmers in their state are under attack by activists who will stop at nothing to paint what happens on factory farms in the worst possible light. “Terrorism has been used by enemies for centuries to destroy the ability to produce food and the confidence in food safety,” the Idaho Republican told his fellow lawmakers while advocating for his bill several months ago. He struck a similar note during our conversation, comparing groups like Mercy for Animals, which has made a name for itself legally capturing wrongdoing on camera, with more extreme groups like the Earth Liberation Front, an eco-terrorist organization known for setting fire to ski resorts and lumber mills.

Farmers and their allies are quick to brush off the unsanctioned animal rights investigations as craven attempts to manipulate the public and undermine the meat and dairy industry as a whole. “Their goal wasn’t to protect the animals,” Patrick said of the Mercy for Animals investigation at Bettencourt. “Their goal was to put the farmer, or in this case the dairyman, out of business.” That, the activists admit, is largely true. After investigations uncover inhumane or illegal practices on big farms, the groups have a history of applying public pressure to any corporation it can tie to that particular farm. In the case of the Idaho dairy, Mercy for Animals publicized an indirect link to Burger King—complete with a still-active webpage, BurgerKingCruelty.com—and successfully pressed the fast-food giant to stop topping its burgers with cheese made from the dairy’s milk. While that didn’t put Bettencourt, one of the nation’s largest dairies, out of business, it certainly hurt its bottom line.

The industry concedes that abuses do happen on farms—how could it not when there is video evidence one Google search away?—but largely dismisses them as the work of bad actors that are the exception to the industry rule. The industry says reporters and the public are welcome behind closed barn doors—just as long as farmers are there to give context and explain the unsightly details. “We have no intent to stop journalists, but we do want them to ask permission first,” Patrick said, noting that he and his colleagues intentionally left their law as broad as they could.

There are plenty of problems with that logic as far as the public good is concerned. For starters, Upton Sinclair didn’t rely on official tours of Chicago’s slaughterhouses before sitting down to write The Jungle, the 1906 novel that was based on his undercover trips into meatpacking facilities and a work that is widely credited with driving widespread regulatory reform. Likewise for the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting of the New York Times’ Michael Moss, who used confidential company records in 2009 to raise questions about the effectiveness of injecting ammonia into beef to remove E. coli.

The AFL-CIO warns that the effort could have a chilling effect on unions by making it more difficult for undercover organizers to land positions at companies where they are unwelcome, a practice known as “salting.” Ditto for whistleblowers, who in theory could be charged under the law if they were to record evidence to back up their allegations, according to the Government Accountability Project, a whistleblower protection and advocacy organization. State lawmakers behind the efforts often voice fears that activists could easily stage abuse where there is none, leaving farmers convicted in the court of public opinion without a chance to defend themselves—although Patrick couldn’t cite any examples of that ever happening.

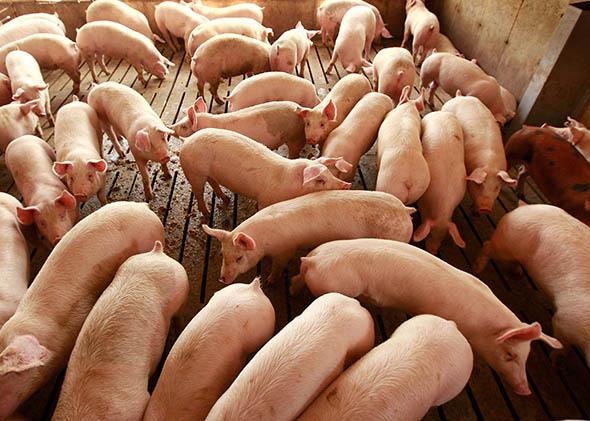

There’s also the arguably more pressing matter of the laws’ main target: camera-toting activists on farm factory floors. While the industry might not like what it sees in the videos, it can’t make a convincing case that the footage has no value. In the last three years alone, activists have taped stable workers in Tennessee illegally burning the ankles of horses with chemicals, employees in Wyoming kicking pigs and flinging piglets into the air, and farmhands in Iowa burning and snapping off the beaks of young chickens. Those actions went undiscovered, or at least unreported, by the farm owners and government regulators before they were caught on camera by muckraking activists.

What they capture on film can go far beyond animal cruelty, too. The footage is capable of shifting the debate from one about the welfare of livestock to that of humans, a topic much more likely to hit home with consumers. The most damning investigation in the past decade occurred in Southern California, where an undercover Humane Society operative caught workers illegally pushing so-called downer cows, those cattle that are too sick or weak to stand on their own, to slaughter with the help of chains, forklifts, and high-pressure water hoses at the Westland/Hallmark Meat Co. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has deemed those cows potential carriers of mad cow disease, salmonella, and E. coli. As a result, the video prompted the recall of 143 million pounds of beef—the largest meat recall in U.S. history—large portions of which were destined for school lunch programs and fast-food restaurants. That investigation would have likely never happened if laws like Idaho’s had been on the books in California.

Both sides are set to get their day in court later this summer when a federal judge hears the suit against the Idaho law. But even if the law is ultimately struck down, the fight will continue. “If it fails, we’ll revise it,” Patrick said. “I know we did the right thing.”