If you pay attention to Tea Party politics at all, you’ve probably heard the phrase “constitutional conservative.” It’s supposed to invoke a certain fealty to the principles of the Founding Fathers: “As a constitutional conservative,” said Rep. Michele Bachmann in 2011, announcing her presidential run, “I believe in the Founding Fathers’ vision of a limited government that trusts in and perceives the unlimited potential of you, the American people.”

It’s tempting to treat the phrase as mere rhetoric, but—as Ed Kilgore explained in the New Republic at the time—that’s far from the case. “[Constitutional conservatism] commonly connotes an allegiance to a set of fixed—eternally fixed, for the more religiously inclined—ideas of how government should operate in every field,” he wrote. “Constitutional conservatives think of America as a sort of ruined paradise, bestowed a perfect form of government by its wise Founders but gradually imperiled by the looting impulses of voters and politicians.”

This isn’t ideology as much as it’s theology, transferred to politics. In particular, it’s the “premillennialism” of fundamentalist Protestantism, which holds Eden as the pinnacle of human existence, and sees the present (and the future) as a hopeless corruption to be abandoned with the return of Christ and the rapture of the faithful.

Let’s ignore its merits as a theological approach; as an approach to history and politics, it’s an impossible sell. In 18th-century America, women were second-class citizens, natives were driven from their land, and blacks were enslaved as a matter of course. And the founders, as self-interested elites, codified this in the Constitution with limited voting rights, disregard for Native Americans, protection for the slave trade, and a compromise that made slavery a political boon for slave-owners.

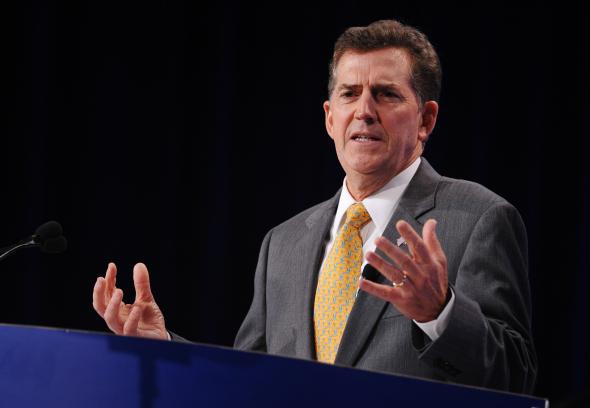

The only way to balance this with constitutional conservatism is to pretend the founders were moral demigods who met and surpassed the challenges of their time. It’s why Bachmann could say, with a straight face, that the founders “worked tirelessly until slavery was no more in the United States,” blind to the fact that George Washington held slaves and Thomas Jefferson was an innovator in the world of slave torment and slave labor. And it’s why, last week, Heritage Foundation President Jim DeMint—who also calls himself a constitutional conservative—could give this gobbledygook take on American abolitionism:

Well the reason that the slaves were eventually freed was the Constitution, it was like the conscience of the American people. Unfortunately there were some court decisions like Dred Scott and others that defined some people as property, but the Constitution kept calling us back to ‘all men are created equal and we have inalienable rights’ in the minds of God. But a lot of the move to free the slaves came from the people, it did not come from the federal government.

It came from a growing movement among the people, particularly people of faith, that this was wrong. People like Wilberforce who persisted for years because of his faith and because of his love for people. So no liberal is going to win a debate that big government freed the slaves. In fact, it was Abraham Lincoln, the very first Republican, who took this on as a cause and a lot of it was based on a love in his heart that comes from God.

To anyone with a cursory knowledge of U.S. history, this is confused. Yes, the Constitution eventually freed the slaves, but only because of the 13th Amendment, adopted in December 1865, 77 years after the ratification of the Constitution. And it wasn’t the “conscience” of the American people or a line from the Declaration of Independence (which, among constitutional conservatives, is conflated with the founding document and given near-divine status)—it was a bloody, apocalyptic war that spanned the country, went for half a decade, and claimed 750,000 lives, including President Lincoln’s.

And while Lincoln was a lifelong opponent of slavery, his push for emancipation was based less on “love” and more on strategy. Influenced by the legal arguments of War Department solicitor William Whiting—who, as a Boston attorney, argued that the president could legally abolish slavery as an “act of war”—Lincoln grounded the Emancipation Proclamation in “military necessity.” It’s why it only applied to the South, excluded the border states, and—in one of many abrupt shifts—encouraged the enlistment of black soldiers.

What of DeMint’s view that emancipation “did not come from the federal government”? If war is the biggest government program of all, then it’s clearly true that the feds freed the slaves. Indeed, the Civil War stands as an inflection point in the development of our national government. Before the war, it was a small operation of limited means. During the war, under Lincoln’s direction and with deep resistance from the small-government conservatives of the day, it ballooned to unprecedented size to meet the demands of the war. It’s why, even now, there are radical libertarians who despise Lincoln as a tyrant who moved America down the road to serfdom.

The point of DeMint’s history lesson—and constitutional conservatism writ large—is to place liberals outside the narrative of American history, and to make liberalism a deviation from the norms of American thought. But the opposite is true—constitutional conservatism is foreign to liberals and conservatives—and the truth is ironic. If there was any period in our history where so-called constitutional conservatives held sway, it’s during the brief life of the Articles of Confederation. Under the Articles, national government was extraordinarily weak—it could not tax, mint coins, or pay collective debts—and states held near-total sovereignty. The result was economic disaster—several states were gripped by depression in the 1780s—and revolt. The failed Articles led American elites to convene a constitutional convention, where they would rethink their approach to national government.

These elites were opposed by the “anti-federalists,” who saw strong government as the prelude to tyranny. Their rhetoric was as hyperbolic as any Tea Partier’s. “A conspiracy against the freedom of America, both deep and dangerous, has been formed by an infernal junta of demagogues,” wrote one.

Indeed, if Jim DeMint wants to sharpen his broadsides against the president, he could do worse than to pick up the Anti-Federalist Papers. Sure, he reveres the founders, but he has much more in common with their opponents.