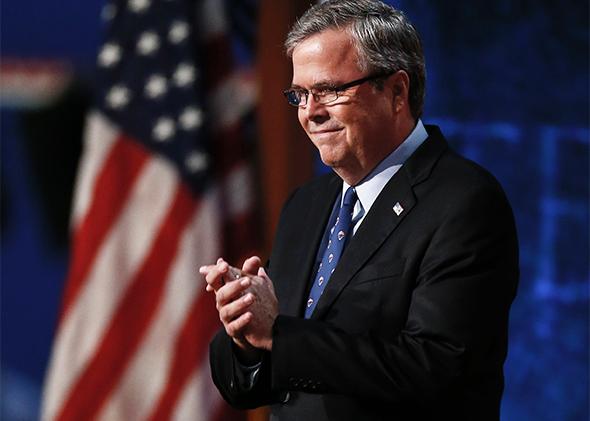

Yes, he’s out of touch with the Republican base, out of shape on the campaign trail, and burdened by the disastrous presidency of his older brother, but Jeb Bush could win the Republican presidential nomination. To make it to the top, however, he’ll have to do one thing: Make “Jeb Bush” disappear.

As it stands, the former Florida governor is anathema to the rank and file of the Republican Party. This weekend, in the key presidential primary state of New Hampshire, conservative activists gathered to listen and judge a handful of presidential aspirants, from all but official candidates like Sens. Rand Paul and Ted Cruz to people flirting with a run like Donald Trump and Mike Huckabee.

Each speaker made his pitch. Paul focused on civil liberties and promised to expand the GOP tent with a hands-off approach to gay marriage and other issues. Cruz billed himself as an avatar of conservative orthodoxy—an economic conservative, a social conservative, and a national security conservative. Huckabee indulged in right-wing hyperbole—“My gosh, I’m beginning to think that there’s more freedom in North Korea sometimes than there is in the United States”—and Donald Trump said Donald Trump things.

But insofar that there was a rhetorical constant, it was open disdain for Jeb Bush, as candidates responded to his sympathy for undocumented immigrants and praise for federal education standards. “Get rid of Common Core and replace it with common sense!” said Tennessee Rep. Marsha Blackburn, taking a swipe at Bush’s support for the reformed curriculum standards. “I think what Jeb was trying to say was that many people come to the United States to look for opportunity,” said Huckabee, commenting on Bush’s support for comprehensive immigration reform. “I don’t personally support amnesty. I think we ought to have a secure border.”

Trump also riffed on Bush’s immigration comments, mocking the notion that immigrants come to the United States out of “love.” “[T]hat’s one I’ve never heard of before,” Trump said. “I’ve heard money, I’ve heard this, I’ve heard sex, I’ve heard everything! The one thing I never heard of was love. I understand what he’s saying, but, you know, it’s out there, I’ll tell you.” More importantly, the mere mention of Bush’s name drew boos from the crowd, who oppose the former governor’s immigration leniency.

The standard take is that Bush’s weak support among grassroots conservatives is nearly fatal for his presidential chances, and there’s no doubt that it puts him at a disadvantage. Bush has been out of the game for so long that he’s out of step with the base of the party. They want a full-scale assault on the welfare state, not compassion or empathy.

Then again, this is an old problem. The Republican Party has a long history of nominating candidates who anger and enrage the base. In 1996 there was Bob Dole, in 2008 there was John McCain, and in 2012—after three years of anti-establishment, Tea Party rage—Republicans nominated Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts who pioneered universal health insurance for his state.

Yes, the actual energy of the party was with Romney’s competitors, from Texas Gov. Rick Perry to former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum. But Romney was the establishment choice. In addition to the cash and organization this provides, it sends a powerful message to the party writ large: “You may not agree with Romney on every choice, but we believe he could win the presidency.” The imprimatur of the GOP’s donor class may not sway every activist and Republican primary voter, but it’s a huge asset to whoever has it and almost guarantees the nomination.

If Jeb Bush has anything on his side right now, it’s this—the establishment stamp of approval. Just read this Washington Post story from late last month, where a parade of Republican donors and officials showed their enthusiasm for a Bush candidacy. Yes, there are still arguments and divisions among Republican elites, but one thing is clear: If Bush steps into the ring, he’ll begin the race with key victories in the “invisible primary,” where candidates fight to win influence and endorsements from the party’s most moneyed supporters.

Even still, this doesn’t make the grassroots irrelevant as much as it changes the nature of the challenge. No, the Republican base isn’t strong or influential enough to drive a candidate to the nomination or to kill the candidacy of someone with establishment support. What it can do, however, is extract concessions in the form of policy promises and rhetorical strategies. This is what happened to Mitt Romney. Strong elite backing made him the favorite for the nomination, but he still had to appeal to rank-and-file Republican voters. After all, you still need to win primaries. So, he disavowed his previous self, condemning the Affordable Care Act as an abomination of public policy and dashing to the right on immigration. He gave his full commitment to the priorities of the Republican base, which—along with the help of the establishment—won him the nomination. In other words, for Mitt Romney the Republican presidential candidate to become Mitt Romney the Republican presidential nominee, he had to go back in time and effectively destroy Mitt Romney, the moderate Massachusetts governor.

“Jeb Bush, former Florida governor” is much more conservative than Romney was at the same stage of his career, and he won’t have to shift gears on health care reform or abortion. Still, if Bush has appeal to Republican elites, it’s because of his moderate affect—he’s not a fire-breather—and pragmatic approach to immigration and education, legacies of his tenure in Florida.

And that’s the “Jeb Bush” that has to go. To win the invisible primary and prevail with voters, Bush will have to sacrifice the most moderate aspects of his persona and commit to the main concerns of the rank and file. Or, put another way, there’s a good chance that any Jeb Bush who represents the entire Republican Party will be a Jeb Bush who opposes comprehensive immigration reform, shows strong skepticism for federal education programs, and adopts the usual bromides against President Obama and the Democratic Party.

It’s a Jeb Bush who—if he truly wants to win the nomination—may have to disavow his brother and father, too. Few Republicans will defend the eldest Bush, who worked with Democrats to raise taxes and earned the animosity of a generation of conservatives. By contrast, GOP opinion on George W. Bush is divided. Among elites, he’s a distinguished ex-president. To many activists, however, he’s a big spender who jeopardized conservative principles. And that’s to say nothing of the general public, which still blames the second President Bush for our sluggish economy.

For Jeb Bush to win, he may have to do more than bury his former political persona—he may have to bury the Bush name.