The path to Alaska’s most infamous home ended at a “No Trespassing” sign and a heavy chain. Joe McGinniss, holding the cellphone he’d been using to give me directions, walked to the makeshift gate and pulled it back. I’d brought some salmon, he had a grill, and we planned to eat dinner while the sun set on Wasilla’s Lake Lucy.

“Don’t take any pictures,” said McGinniss. “I had a party here a few nights ago—20 or so people came by—and everyone was very good about not taking pictures.”

It was hard to resist, but this was July 2010, and the story that would accompany any pictures was played out. In May, McGinniss—the well-known political journalist and true-crime author—had rented a vacant home right next to Sarah Palin’s, where he would research and write a biography of the former governor. A horrified and media-savvy Palin wrote a Facebook post, alerting her supporters to the news that a journalist was “about 15 feet away on the neighbor’s rented deck overlooking my children’s play area and my kitchen window.”

In between reading hate mail and changing his phone number, McGinniss had called me to describe his life under siege. “Look, this is a pain in the ass for them,” he told me. “If I were her, I’d be upset.” But in the same conversation, he fueled the haters by suggesting that “Sarah should have baked a plate of cookies, and come around the fence, and said, ‘hi, and laughed about this.’ ”

I’d blown off most of a dinner with friends, hiding out in their bedroom, to type up what McGinniss told me. It felt like someone was being exploited in Neighborgate, but I couldn’t tell who. If you cover politics, you’ve read The Selling of the President 1968. A 26-year-old McGinniss wrote that book from inside Richard Nixon’s campaign, gaining access that no reporter would ever again fool a campaign into giving. If you’re a reporter, you’ve probably read The Journalist and the Murderer, Janet Malcolm’s study of the legal battle between McGinniss and Jeffrey MacDonald. At least you know the first line: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.”

McGinniss, I figured, knew exactly what he was doing. One month later, I resigned from a reporting job after mean emails I’d sent to a listserv were leaked. More than a few conservatives remembered that I’d sided with McGinniss over Palin. McGinniss remembered, too. When I used some of my unexpected time off for a personal trip to Alaska, McGinniss invited me to come see the house, and to stay over if so moved.

“My lawyer from LA, who just departed yesterday, opted for the Best Western after he took a look here,” McGinniss wrote in an email. “He didn’t regret it.”

The house, as other guests would report, was comically close to Palin’s. Alaska’s first family had built a grand home that filled much of their lot, and put up a fence with the braces pointed toward their neighbors. By the time I got to Wasilla the Palins had tacked on extensions that raised the fence 14 feet high. From the porch or the dining room you could see over into the yard. McGinniss didn’t care. He was half rattled, half amused by the campaign against him, after he’d been so kind as to hand-deliver a copy of his book about Alaska to the Palins’ front door.

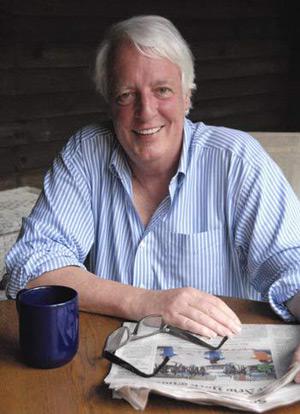

So we talked, and quickly got bored with the Palins. McGinniss told stories about the golden age of magazine journalism, how he’d gotten unthinkable contracts for travel stories. How his true-crime books sold, but his passion project about an Italian minor league soccer team hadn’t. How the Palin book, hopefully, would. He pointed out where he’d be running cable to watch the World Cup and (politely) argued that the salmon a friend had caught was better than the stuff I’d bought at Wasilla’s Walmart. I didn’t dispute him. I didn’t stay the night, but returned in the morning to meet McGinniss at a diner. My source had unexpectedly become a friend.

And he stayed a friend. McGinniss was curious and generous, trading emails or calls as he (figuratively speaking) watched Palin’s moves. After Joe Miller bested Sen. Lisa Murkowski in a Republican primary, McGinniss sent me an email with the subject “Not that it feels good to have been right” and a copy of the tip he’d given another friend to “keep an eye on this ultra Tea Party challenger.”

He lived with the Palin story, but it wore on him. Some days there’d be a painstaking email about how he interviewed a source (a free lesson in the art), and some days he’d forward news about the insanity of the Mat-Su Valley. I shared the news that Levi Johnston, the father of Palin’s grandson, would drop his quickie memoir the week before McGinniss’ book came out. “The publisher of that division of S&S passed on my Palin proposal in 2008,” wrote McGinniss. “So she winds up with Levi instead.”

McGinniss’ book was published in September 2011. He fretted about the sales, because “Sarah seems to have no fans left even among conservative media,” but when it hit the New York Times best-seller list he proudly told me about his new historical footnote. “Random House is not aware of any prior instance in which a nonfiction author has had a Times top-ten bestseller 42 years after his or her first.”

Palin’s fans were outraged, just as McGinniss expected. Breitbart.com published an email that purportedly showed McGinniss telling a source that he needed more proof before putting a story in the book. “My reporting continued beyond the date of the email,” McGinniss told me, going on to mock his critics and attach a few more examples of how he went back and forth with sources who teased scoops or demanded money.

“I go to where the story is,” McGinniss told me. “I don’t sit in my office and pass judgments designed to get me airtime on Sunday mornings. I work sources. That’s called journalism. It’s not always pretty, but without it, all we’d be reading are ghost-written celebrity memoirs. The homicide detectives I’ve gotten to know over the years have told me that their line of work isn’t always fun either. But it’s a necessary part of the effort required to keep our society from becoming any more dysfunctional than it already is.”

Weeks later, when Palin announced that she wouldn’t run for president, my friend who’d spent a year of his life researching this subject sent me a terse email: “No surprise. Glad the show is over.” He moved on from politics, happily so, returning to true crime stories and eventually re-reporting the Jeffrey MacDonald case for a lengthy e-book. From time to time he’d email to criticize some horse race journalism that he found particularly stupid.

“The media have been dying for a neck and neck race because they needed viewers and page views, which lead to advertising, which they’re dying without,” McGinniss wrote after reading a story about the Obama–Romney race. “There’s no orchestrated conspiracy, but it’s understood in [the mainstream media] that ‘the closer we can make it seem, the better we’ll do … and, boy, are we ever in need of ad money.’ ”

What I didn’t know, what McGinniss didn’t reveal until January 2013, was that he spent most of the election year being treated for advanced prostate cancer. He headed to the Mayo Clinic, where a doctor named Eugene D. Kwon introduced him to a just-approved, miraculous-seeming drug called ipilimumab. McGinniss reacted to this in the only reasonable way he knew how: He pitched a book. Last May, he sent me some passages from the proposal.

“I’m planning to write a book about Kwon from the dual perspective of author and patient,” McGinniss wrote. “My personal story—the last chapter of which remains unknown—will provide a narrative thread, but the larger story will be about an institution that is already a household name around the world, and its charismatic hero who is on the leading edge of a revolution in new modalities of cancer treatment.”

McGinniss died yesterday, before the story could be told the right way.