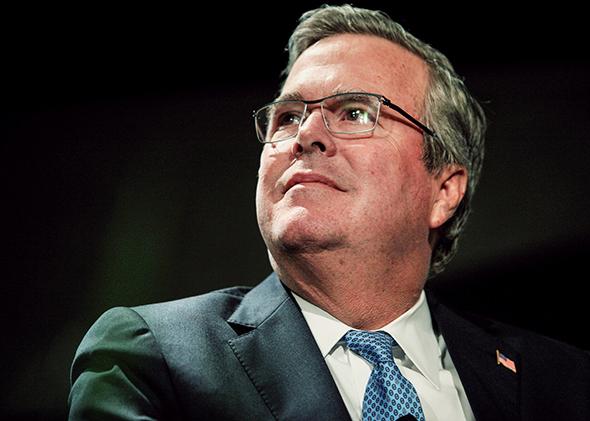

Jeb Bush is having a moment. For two months or so, as Chris Christie’s presidential fortunes have appeared abridged, people who have supported the New Jersey governor (or at least are predisposed to support him) have started mentioning the former two-term Florida governor as a possible 2016 candidate. Should the federal investigation into the George Washington Bridge lane closures become a full-blown calamity, several have said, perhaps Bush could be lured into the race. Now the Washington Post’s Philip Rucker and Robert Costa report that the whispers have grown into a draft-Bush movement.

The argument for a Bush run is that he has a governor’s executive skills, can forge a relationship with crucial Hispanic voters (particularly in a key swing state), and has a fundraising base founded, in part, on a reservoir of goodwill toward the Bush family. Republicans are sick of being out of the White House and want a winner. Perhaps, but Bush is also the perfect candidate if your goal is driving simultaneous wedges into as many fault lines in the Republican Party as possible.

The first problem is his heritage. On domestic issues, the Bush family is synonymous among some conservatives with tax increases and federal spending. Perhaps the greatest sin in the modern conservative movement is George H. W. Bush’s 1990 budget deal where he traded tax increases for budget savings. Jeb Bush, on the other hand, has cited his father’s compromise as the epitome of presidential leadership. George W. Bush is criticized for his lack of spending restraint as well as his support for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (which some might count as the second greatest sin).

In his positions on fiscal policy, Jeb Bush has given comfort to the suspicious. When asked about the hypothetical trade-off posited during a 2012 GOP debate, where no GOP candidate would accept a dollar of tax increases in exchange for 10 dollars in spending reductions, Jeb Bush took a different view. “If you could bring to me a majority of people to say that we’re going to have $10 in spending cuts for $1 of revenue enhancement—put me in, coach,” he said at the time. He has also criticized Grover Norquist’s no-tax pledge that few GOP lawmakers refuse to sign. Bush even joked during a budget hearing two years ago that these positions “will prove I’m not running for anything.”

The GOP is having a robust debate about foreign policy that is likely to continue into the primaries in 2016. If Bush runs, he will have to field a greater share of questions about the war in Iraq than anyone else. He is appealingly loyal to his brother and father, but managing their legacies will lead to distracting fights, or at the very least increased stress as his opponents, Twitter, and the media bait him time and again.

The second problem for Bush is the people backing the draft movement. He isn’t being called from the counter in coffee shops or Tuesday Tips club meetings. The support is coming from what one GOP veteran referred to as “the donor class.” This group is also variously referred to as the establishment, Country Club Republicans, and the moderate wing of the party. These Republicans are tired of being defined by the unpopular Tea Party wing of the party. Meanwhile, movement conservatives are sick of elites using their money to arrange things without the interference of pesky voters. This, they believe, has led to support for squishy candidates like John McCain and Mitt Romney who wind up losing anyway. Bush would enter the campaign wearing the establishment tattoo and carrying the burden of its past mistakes.

The final problem is that Bush has taken policy stances against his party’s grass roots on the hot button issues of immigration and education. Bush is an advocate for pathways to citizenship and residency for illegal immigrants, positions that House Republican leaders didn’t even want to debate in this election year for fear they would cause too big a rift in the ranks. Bush is also an advocate for Common Core education standards, which advocates like Bill Gates say are designed to make the United States more competitive in the world. Grass-roots conservatives are passionately opposed to the standards, arguing that they remove local control of education and dumb down teaching of crucial subjects like math. In Indiana, activists have just convinced GOP Gov. Mike Pence to withdraw the state from Common Core.

The tensions that a Bush candidacy would exacerbate have existed within the GOP since the New Deal as members have wrestled with whether to pick a candidate with the best perceived chance of victory or the one who best reflected the philosophy of the conservative movement. Even in 1952, war hero Dwight Eisenhower, the darling of the GOP middle, had to fight off a close battle with Sen. Robert Taft. The Ohio senator was considered a better conservative, but party wizards worried he couldn’t win because of his dour personality.

These fights are robust, though they do not doom a candidacy. Sometimes they are the necessary clarifying battles that lead to victory. But they are exhausting. Bush has never run at the national level, which Texas Gov. Rick Perry discovered can be very different from having the hot hand at home. Bush has also not run in a race since 2002, an age before Twitter, Facebook, and the towering and repetitive pettiness of the modern presidential campaign. He has a shorter supply of inner sunshine than his brother that would get exhausted by lunchtime on most campaign days.

It would be in keeping with Bush’s description of himself as an “eat your vegetables” politician if he challenged the orthodoxy of part of his party in his campaign instead of trying to skirt his challenges. If he replaces Christie and becomes the new establishment front-runner then a battle is coming.