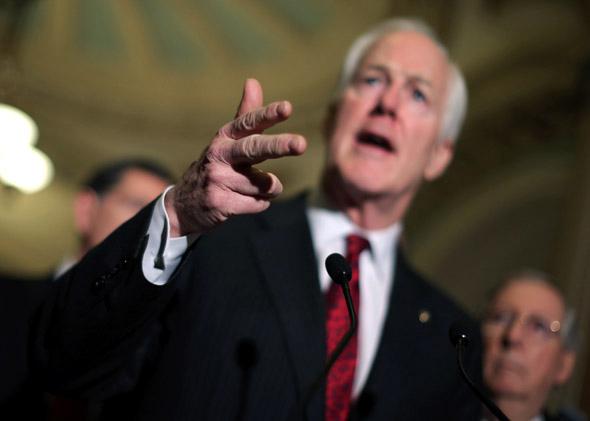

HOUSTON—A pattern was beginning to emerge: Sen. John Cornyn entering a room and discovering people who sound much more conservative than he sounds. On Tuesday morning, shortly after early voting began in his primary, the senior senator from Texas rolled into the offices of a local courier service to accept an endorsement from the National Federation of Independent Businesses. He shook hands and took his place at a table of job creators, asking them for ideas to bring back to Washington, apologizing for what the city had wrought.

“What I regret is that the federal government, instead of facilitating what you do—encouraging it, incentivizing it—is doing the opposite,” said Cornyn. “[Former Sen.] Phil Gramm used to talk about doing the Lord’s work in the devil’s city. Sometimes I think it’s like a forward operating base in hostile territory.”

Will Newton, the well-attired executive director of the NFIB in Texas, went with it. “One of the old leaders of the NFIB in Washington is famous for saying that he considered Washington, D.C., a ‘work-free drug zone,’ ” he said.

Everyone broke out laughing. So did Cornyn. A little while later, a trucking company owner named Darrin Forse went on a tear.

“You get people to come in and apply for jobs,” said Forse. “First thing they ask is, ‘What’s it gonna pay?’ The government’s giving them whatever they want anyway. A lot of them come up and sign a card and say, ‘OK, I can get another free check and whatever else.’ That’s what’s happened. They’re getting their insurance for nothing, and here we are, the working people.”

Cornyn’s eyes darted around the table, seeking someone else to talk to, finding him in another businessman who’d talk more generally about Obamacare. The roundtable only lasted 30 minutes, and the crowd wasn’t hostile. It just wasn’t satisfied as the senator explained that the GOP could finally deliver for them if it won six more Senate seats. It wasn’t quite satisfied with Cornyn. Still, Cornyn isn’t losing.

Observers outside Texas have not convinced themselves of this fact. Last week Cornyn joined GOP Senate leader Mitch McConnell and cast a vote for a one-year delay in the debt limit, punting the issue past the 2014 elections. In Washington this was portrayed as Frodo and Sam locking arms and walking to the mouth of Mount Doom.

“[Sen. Ted Cruz] had forced McConnell, Sen. John Cornyn of Texas and other Republicans to cast votes that could cause them to lose primaries to weaker general-election candidates,” wrote Dana Milbank.

“Mr. McConnell and Mr. Cornyn chose to expose themselves to primary attacks,” wrote two of the New York Times’ lead political writers.

The open secret is that Cornyn isn’t facing a typical primary challenge. He’s facing the sort of “threat” that used to meet incumbents in the Bush years, before the Tea Party, when a few candidates would put their name on the ballots, spend a few thousand dollars, and lose. McConnell’s consistently ahead of his primary opponent, but Cornyn is seen to be so far ahead of his field that the usual Texas pollsters haven’t even bothered checking. The void has been filled by polls paid for by conservative media. The latest poll, which suggested that Cornyn could win less than 50 percent of the vote in the primary and be forced into the runoff, ricocheted around a movement/Twittersphere/blogosphere that badly wants a race.

Cornyn’s opponents want a race, too, though it can be hard to tell. Hours before the filing deadline, four months before the vote itself, East Texas Rep. Steve Stockman entered the race. Few Texans have seen him since then. Stockman had won in the 1994 GOP wave, lost in 1996, spent nearly a decade caring for a father with Alzheimer’s, and returned in one of the new seats created by redistricting. He legislated by tweet and by press release, all crafted with care to get “likes” on the right and outraged reactions on the left.

That’s exactly how he’s run for Senate, a race he started nearly $100,000 in the hole. One campaign office was condemned. After he tweeted, “If babies had guns, they wouldn’t be aborted,” and it caught on, he started selling the recycled quip as a bumper sticker. Reporters don’t know where he’s campaigning, or whether he’s campaigning at all—when I asked a spokesman, he said, “We’re not interested.” On Tuesday, as Cornyn campaigned in Houston, Stockman’s campaign Twitter account claimed—five times—that Cornyn had declared Ted Cruz a “threat” to the nation.

Cornyn hadn’t even said that. It didn’t matter. The point was that he wasn’t Ted Cruz, that Cruz had managed to win a primary in 2012 by making it into a runoff, and that conservatives could force Cornyn into a runoff if they believed hard enough. The point is that every conservative knows at least a few people who want to protest Cornyn. Some of them even show up to his rallies.

“I can’t say I’m against the senator,” said Bud Johnson, a businessman who showed up at the NFIB roundtable. “I’ve just got a real problem with the growth of Washington. When I was in graduate school, I used to get the federal register delivered to my house. It was a few pages. I think it was 75,000 pages last year. When we start controlling the light bulbs in people’s homes, we’ve gone awry.”

Two days earlier, in the East Texas town of Longview, Cornyn had joined Karl Rove and country singer Neal McCoy for a two-hour fundraiser and jamboree. Mickie Hand, a local Republican parliamentarian, danced in the aisles as McCoy’s band played a cover of “Billie Jean.” Her necklace, a cross built with nails, swayed as she moved. She paused just long enough to condemn Cornyn’s debt limit vote.

“If every household did that, we’d be broke,” said Hand. “But we have a good senator in there who has time, who’s worked his way up. I’m very hesitant to get rid of that for someone who’s not overwhelmingly better.”

Over a long afternoon, I heard many, many iterations of that sentiment. Cornyn was tolerable at best; his opponents weren’t worth looking at. One Longview donor who’d shelled out to attend a pre-jamboree fundraiser with Cornyn and Rove started to tell me that her party needed to recapture the center, or else it couldn’t win in Texas. Realizing what she’d said, she asked me not to use her name.

My search for some actual enthusiasm led me to a college auditorium in Arlington, Texas, where the six Senate candidates who were not Cornyn or Stockman held their final pre-vote debate. One of them, Ken Cope, had asked Stockman to quit the race because his “antics and embarrassing actions will steal the limelight from the serious candidates.” Another candidate, Dwayne Stovall, actually knew Stockman.

“He’s not a stupid guy,” Stovall told me over chips and salsa at a sports bar near campus, as a trio of undergrads sang along to Beyoncé songs on an iPhone. “He’s been perpetually trying to be a politician for decades. I think he saw the writing on the wall and said, Cornyn’s gonna be in a runoff. The polls said that six months ago. He rolled the dice. I just wish I knew that when we had breakfast two weeks before he got into the race and he asked how much I’d raised. If I’d have went, ‘I have $5 million in the bank and I’m gonna whip him!’ then I don’t think he’d have gotten in.”

Stovall had not raised $5 million. He was running $4,975,000 short of that. He was driving around Texas, trying to sync up campaign events with the schedule of his emissions-testing business. “You’re looking at a guy who puts 100,000 miles on his car every year,” said Stovall. He’d showed up at Tea Party meetings and candidate forums, winning endorsements after nine of them.

And it was easy to see why. Stovall, a former high school wrestler with a shaved head, described a political awakening that started when he was traveling internationally for his old business, linking up with builders in Japan or the Middle East. They explained all the benefits that came America’s way because the dollar was the reserve currency. Stovall looked at America’s debt obligations and imagined how the party would end. “There’s not enough currency in circulation on the planet to pay that off,” he said, “and yet we think we can keep on doing it.”

Stovall had gotten some pre-primary publicity, finally, with that old standby of the underfunded candidate: a viral YouTube video. In his most widely circulated statement of principles, Stovall sat on a pickup truck with his dog and listed the crimes of John Cornyn. “You don’t stab her in the back by voting for cloture on Obamacare,” he said, referring to Texas. “You don’t enslave its children with unconstitutional laws and overwhelming debt. And you certainly don’t do all this to please some guy that looks and fights like a turtle.” Cue: a picture of Mitch McConnell and a cartoon turtle.

Stovall thought the ad was ridiculous. He’d shot it weeks before, and told the campaign not to run it. Then came the debt vote, which made the ad look prophetic; Stovall told his team to “cut it loose.” The attention paid to that video boosted him almost as much as it depressed him. “You talk about the Congress enslaving your kids and future generations for no other reason than to grow this government, nothing. You put a talking dog and a turtle in the media, and people talk.”

Tuesday night, Cornyn’s campaign arrived at a Republican donor’s home in the exclusive Royal Oaks neighborhood of Houston. Young professionals, neatly dressed from days at the law firm or the medical device company, paid $25 each for a meet-and-greet. The whole thing was put on by Maverick PAC, started by veterans of the George W. Bush campaign who now find themselves representing the center, if not the left, of their party. They drank wine or light beer and ambled through the house until about 8 o’clock, when Cornyn and local Rep. Ted Poe were shepherded to the living room.

“Personal involvement is what’s required for a democracy to secede,” said Poe. He corrected himself. “Succeed! Not secede. That’s what Texas is gonna do!” Everybody laughed at the accidental joke, but just in case, Poe waved his hand, looking at Cornyn, as if deleting the comment in the air. The senator took his place.

“It’s pretty hard for anybody to get to my right, I have to tell you, when it comes to the issues,” said Cornyn. “It’s important to welcome people who maybe don’t agree with us 100 percent of the time. The fact of the matter is that that’s an impossible standard. How do we accomplish 80 percent of what we want?”

The young professionals, people who’d be funding Republican campaigns for decades to come, nodded and kept listening.

“I’ve found this to be an irrefutable rule of politics,” said Cornyn. He brought his right hand down on his left, like a gavel hitting a desk. “The candidate who gets the most votes wins.”