HOUSTON—Larry Cohen, the president of the Communications Workers of America, entered the conference room where he’d meet the press. He looked a little dour.

“Chattanooga is the next Madison, Wisc.!” said one of the 10 reporters who’d shown up to talk to Cohen. “Nice line.”

Cohen laughed. He’d deployed that tagline after workers in a Chattanooga, Tenn., Volkswagen plant voted 712–626 against forming a union and joining the United Auto Workers. It was a crushing defeat for the labor movement, one that much of the media didn’t expect—one that labor absolutely didn’t expect. Volkswagen had not opposed the union campaign. After the vote, the company continued to favor a “works council” in Chattanooga, of the sort that exists in Germany but not in the United States.

Not much comfort there. This week’s meeting of the AFL-CIO’s executive council was supposed to follow a triumph. It was starting with recrimination. A right-to-work group founded by Grover Norquist had placed ads and bought billboards in Chattanooga. One billboard portrayed some urban ruin under the legend DETROIT: Brought to you by the UAW! The Koch brothers had opposed the union. Tennessee Sen. Bob Corker, a former mayor of Chattanooga, had gone so far as to claim he’d “had conversations” that convinced him “that should the workers vote against the UAW, Volkswagen will announce in the coming weeks that it will manufacture its new midsize SUV here in Chattanooga.”

“It’s a turning point,” said Cohen. “It’s not so much a turning point in terms of working people and how they behave, but to have a U.S. senator, who takes an oath of office to be part of the federal government, ignore the preamble to the National Labor Relations Act, which clearly states that it’s the policy of this government to promote collective bargaining. Instead, he attacked it.”

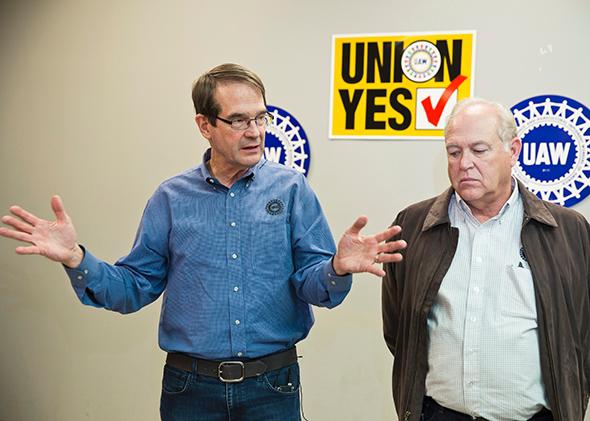

What would the labor movement do to Corker? He was re-elected in 2012—there’s nothing to do but fulminate about finding “accountability” for what he and Tennessee Republicans did (this was the AFL-CIO’s official statement), “legally, politically and economically.” Their opponents had revealed, in the words of AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, some “new forms of right-wing zealotry.”

“They came within an eyelash of winning against enormous odds,” said Trumka, speaking of the organizers in Tennessee. “Not that long ago, this kind of a union election in Chattanooga would have been unthinkable, but today it was very real and very alive.” Over a weekend and three work days in Houston, the labor movement attempted to prove that it had only begun to fight in the South and that the 2014 election could be salvaged for Democrats.

Actually, that one was easy: Unions would campaign for the minimum wage. “Rising wages and everything that means is right in front of us to seize and to expand upon,” said Trumka. “Leaders from the pope to the president are now talking about it, embracing it, heralding it.”

The pope and the president, but especially the president. At the State of the Union, he’d Xeroxed and prettied up a plan by House Democrats to hike the minimum wage for federal contractors all the way up to the ideal $10.10. As the AFL-CIO met this week, he was still campaigning for it. Democrats in tough state races, too—Illinois’s Gov. Pat Quinn, whose ability to win elections has endured despite deep unpopularity, is campaigning for it and blaming the Republican House of Representatives for blocking it nationally.

“It’s raising wages, it’s six days, it’s benefits—it’s people saying, ‘I’m playing by the rules, and I’m losing,’ ” explained Trumka. “If the American public has its way, they will want to debate around raising wages.”

Is this really up to the “American public?” Labor, as evidenced by the Chattanooga election and the 2012 loss against Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, has image problems. The Affordable Care Act does, too. Both are being ripped apart by, yes, expensive campaigns funded by wealthy people with no-limit credit cards, but the Affordable Care Act’s rollout problems and sticker shocks aren’t helping it.

In a state like Texas, it’s easy to start a conversation and marvel as it careens into a diatribe about the costs of Obama-mandated health care plans. Between sessions at the Hilton Hotel where the AFL-CIO was meeting, I talked to John Manlove, a Republican businessman and former mayor of a Houston suburb who’s currently locking up endorsements for a March 4 congressional primary. He was infinitely less “volatile,” as he put it, as the congressman who’s leaving the district—Rep. Steve Stockman. He described the plight of one of his daughters, whose first baby was born for free at home, and who now has to shell out “$5,000 for the second baby because she has to have an insurance policy.”

The Affordable Care Act did not factor into the AFL-CIO’s Houston pitch. A new poll, released at the conference, tested the popularity of sick leave and child care in the swing states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Florida. Not polled: anything else about health insurance. I asked Michael Podhorzer, the AFL-CIO’s soft-spoken political director, if the ACA was going to aid or anchor union-backed candidates.

“In a separate poll, basically, for the two state governors who expanded Medicaid, it was seen as a positive by voters,” he said. “It made voters in the other three states less likely to vote for Republicans. So far what we’ve seen is that the Republicans are making the Affordable Care Act a central issue of the federal campaign, and you can see that in the ads that are already being run. I’m not sure how much that’s going to be the frame for the governors’ races. I think they’ll be more localized.”

If you go back to 2010, you can find labor leaders using some of the same words. In 2010, more than $50 million flowed from the AFL-CIO into campaigns to elect Democrats. The Democrats lost a generation of leaders and battles anyway. Labor will keep organizing in the South and keep trying to save the Democratic Senate. The president and the pope were on board for at least some of that. But the pope has only won one election. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Grover Norquist, and the Koch network put that to shame.