Morton Blackwell was going to lose, and he knew it. He was just one of 168 voting members of the Republican National Committee, just one member of the standing committee on rules, and he knew he’d be steamrolled when he tried to change those rules. The next Republican primary would be fought largely along the stricter guideline set up at the 2012 GOP convention in Tampa—set up by the victorious allies of Mitt Romney, people who should have stopped mattering by now.

“The only reason it passed is that it was forced down our throats,” said Blackwell, standing at a microphone and facing the committee heads. “The case has been made that there are many people who favor no proportionality at all, and favor a one-day primary. I dispute that. I would like a show of hands—how many people on this committee would favor a one-day primary? I know how Ron Kaufman feels, but anybody else?”

Blackwell’s RNC peers got a chuckle out of that one. Kaufman, a Republican operative who is inevitably described as an “influence peddler” and never quibbles, had backed Mitt Romney in 2012. He’d helped the RNC undo all the reforms that loosened that primary, allowing—in Romneyland thinking—a bunch of losers to drag the candidate into extra primaries and debates. When Blackwell joined a convention floor protest of the new rules, trying to restore the power of state conventions over party-sanctioned primaries, the mics were cut off.

“I’ve represented Virginia on the RNC since 1988,” Blackwell told Tea Party activists after the vote. “Nothing like this has happened before in living memory at a Republican National Convention.”

Two years later, when Blackwell went after Kaufmann, he was gaveled out of order.

“Mr. Blackwell, we are not going to allow personal attacks or snide comments,” said the rules chair.

“It’s not a snide comment,” said Blackwell. “I think Mr. Kaufman is proud of his position.”

He probably was; he was winning. A few hours of family feuding later, the RNC had protected the rules that set up a tighter, shorter primary, focused on coronating a front-runner as quickly as possible. Only four states would vote in February—Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada. For the first two weeks of March, states would have to assign delegates proportionately; after that, they could go winner take all. The convention could happen as early as June. This was all designed to defeat the Democratic candidate—“she who must not be named,” as RNC general counsel John Ryder put it.

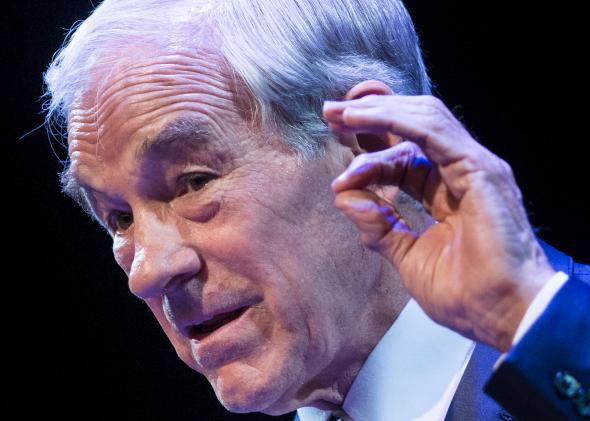

The affirmation of the tighter rules was just the latest and most public victory by a Republican establishment that believes it had gone too easy on insurgents. On Tuesday, Iowa Republicans met for their biennial precinct caucuses. In recent years, these had come to be dominated by the “freedom movement” that supported Ron Paul for president. Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad printed up at least three fliers encouraging Republicans to show up, implicitly to out-vote the Paul faction.

Three days later, Iowa GOP Chairman A.J. Spiker was at the RNC meeting, downplaying the Branstad move. “People talk about that, but who isn’t a Branstad delegate?” asked Spiker, who was lifted up to the chairmanship by the Paul movement. “I mean, I support the governor’s re-election. Everybody’s going to be a Branstad delegate. It was average turn-out—Bob Vander Plaats pushed turn-out with his evangelical group, the state party pushed turn-out, liberty people pushed turn-out. I saw anti-common-core people there.”

That’s just it, though—the Republicans outside of Paul’s movement, or outside the Tea Party, will not be caught slumbering again. “We tried to always be nice to them,” grumbled rules committee member and Pennsylvania GOP Chairman Rob Gleason, “but you know what? It didn’t go their way, and they left.” In Utah, party grandees are trying to end the convention system that unseated Sen. Bob Bennett in 2010 and created a primary challenge for Sen. Orrin Hatch in 2012. Inside the RNC, the Paul-friendly activists who took over state parties recently have been co-opted as much as possible.

It’s a slow process, but Blackwell’s charge didn’t really halt it. Spiker was invited on a junket to Taiwan. James Smack, a Paul supporter in Nevada, went from party chairman to RNC committee member, and was invited into a working group to find a compromise on the rules. They fell far short of what Blackwell wanted. After one vote, the defeated Blackwell marveled at how Smack had been “worked on.”

Smack, who wore a “STAND WITH RAND” button above his party identification badge, saw it differently. An insurgent candidate could use this calendar and these rules to win, according to Smack. “It’s going to have to be a solid, grassroots candidate,” said Smack. “It’s going to be someone who competes in those first four states and can break through in that two-week proportionality period.” And as long as a caucus state didn’t hold a “preference poll,” the kind of event that pulls in national media—well, sure, it could still be up to activists to swarm a state convention for their candidate. “There may be a legal challenge or two that comes down the line,” said Smack. “I know Nevada’s not going to bring one.”

The Ron Paul insurgency is turning seven years old this year. It’s what got Smack back into politics. That and his outrage at local laws against pit bulls. As we finished talking, Smack’s wife appeared with a cellphone loaded with photos of their beloved pit bull.

“His name is January Genuine Midnight son,” she said.

“His name is Bruiser,” corrected James Smack.

These were the kinds of Republicans who’d discovered or rediscovered politics at the end of the Bush era or in the early Obama years. These were the sorts of people who’d terrified the “establishment.” For now, outnumbered, they were going along with limits to their power in the cause of defeating She Who Must Not Be Named.