HERNDON, Va.—“We’re going to stick with the founders,” said Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli. “We need people to know that Nov. 5 in Virginia is a referendum on Obamacare!”

The place: A conference center nestled in the unending concrete yawn of Fairfax County, Va. The audience: At least 300 cheering Republican voters, there to sign up for the final stretch of Cuccinelli’s gubernatorial campaign and to see special guest Sen. Rand Paul. The message: The last way that national Republicans want this race to be perceived. If these are the final days of Ken Cuccinelli’s political career, as the polls suggest them to be, the wider Republican Party wants to say a safe, spinnable distance away from the smoldering wreckage.

What was supposed to be a competitive race for governor between two unpopular candidates is in danger of turning into a rout. Terry McAuliffe, the former Democratic National Committee chairman, has overcome a series of financial scandals and a governing record that consists of Meet the Press appearances to build a 10-point lead over Cuccinelli. No Democrat has built that sort of lead in a Virginia gubernatorial race since 1985. No Democrat has won this office while a member of his party was in the White House since 1965. And those records are going to be busted by Terry McAuliffe? It baffles Republicans.

But in person, it’s not baffling at all. On Tuesday, Cuccinelli and McAuliffe hit the trail just 10 miles apart, in separate Northern Virginia suburbs. Cuccinelli is currently losing these suburbs by 24 points and was being outspent on TV even before one of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s shell groups started spending money here. It’s getting more liberal as more government contractors and nonwhite voters move in. McAuliffe has effectively disqualified Cuccinelli with these people, telling them with incessant TV ads that the attorney general opposes legal contraception and shutters abortion clinics.

Cuccinelli’s Fairfax rally was meant for the other voters, the ones being outnumbered. Shortly before 3 p.m., they streamed in, signed up for get-out-the-vote operations, and picked up Cuccinelli or “I Am the NRA” signs being passed out by volunteers. When Cuccinelli arrived, it was side by side with Paul, the two of them hoisting 64-ounce Double Big Gulps.

“I heard Mike Bloomberg wanted to buy the governor’s office down here,” Paul explained, “and I figured after he took my Big Gulp, he’d come after my guns.”

Earlier in the day, in Lynchburg, Va., Paul had warned conservatives that genetic testing could lead to a dystopian eugenic future. He stayed away from that in Fairfax, delivering a shorter version of his speech about the dangers of war-on-terror policing. “They’re writing one warrant to apply to millions and millions of people,” said Paul. “We fought the Revolution because we were mad about the British soldiers coming into our homes to enforce the Stamp Act.”

“And we won!” yelled a Cuccinelli backer.

This was rather disconnected from the issues of the gubernatorial race. In his own 24-minute speech, Cuccinelli stayed closer to the point, deriding McAuliffe as an obvious charlatan and fool who would do the bidding of the Democratic Party. “Remember when he was running on GreenTech?” said Cuccinelli, referring to the electric car company McAuliffe founded after his failed 2009 run for governor. “Two federal investigations later, he’s not talking about it so much!”

Cuccinelli’s audience knew every beat of this. They were, generally, well-versed in talk radio and aware that a McAuliffe win would boost the people he spent his life working for—the Clintons. “Hillary Clinton? I hate her,” said April Hudson, a libertarian-minded Cuccinelli supporter. “I think she’s a murderer. I think she should be in jail. She disgusts me. Everything she did in Benghazi, it disgusts me. She should be disqualified from running for president.”

“Virginia’s a real plum for the Clintons,” said Margaret Hobble, a Cuccinelli supporter from Winchester, Va. “Hillary and Obama worked under the same man, Saul Alinsky.”

The point of this rally was to rev up the Republican base, in the hope that the April Hudsons have more clout than they do when turnout is higher on the other side. Before the race is over, Cuccinelli will have stumped with Paul, former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, former presidential candidate Rick Santorum, a crew of conservative state attorneys general, and the radio host and author Mark Levin. Off-year Virginia electorates are whiter and older and more conservative than the electorates that elected Barack Obama twice. “We’ve got to close like we’ve closed every race we’ve been in, and that is—better than the other side,” said Cuccinelli. He evoked the memory of a 2007 state Senate race that he won after days of recanvassing ballots. “You know what they call you when you win an election in a recount? Senator.”

But apart from the die-hards, few people expect this race to be in the margin for a recount. I drove up the road to Herndon, Va., stopping at one of the convenience stores that remind Republicans every day of how the region is ebbing away from them. Outside, a few groups of day laborers loitered away the afternoon. Inside, a mostly Hispanic clientele wandered past the bargain stacks of Corona and Modelo Especial to buy Red Bull and—yes—Big Gulps.

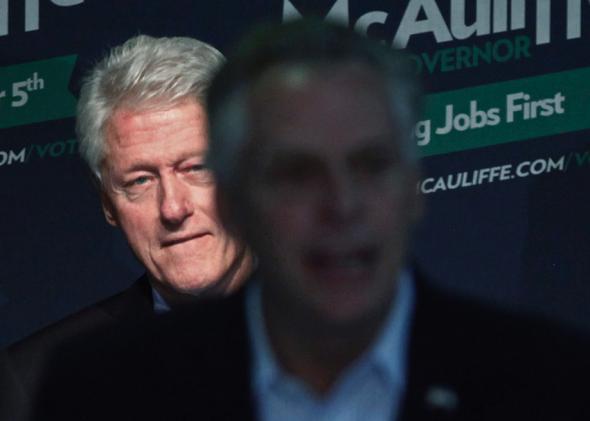

And a few minutes away, the line for McAuliffe’s rally stretched around most of Herndon Middle School. Bill Clinton was coming in for the sixth event on a nine-stop “Putting Jobs First” tour. Mark Herring, the state senator who’s running for attorney general with McAuliffe, worked the line and told voters that his opponent, Mark Obenshain, was a Cuccinelli cheerleader. This is the closing message that has built a small lead for Herring in the only race that still seems competitive.

Photo by Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Cuccinelli’s rally had felt like a typical state election rally. McAuliffe’s was inflated to presidential campaign proportions—multiple checkpoints, special guests, personalized media tags, PA blasting the U2 and Bruce Springsteen songs that every Obama campaign embed still hears in his nightmares. Volunteers roamed the gymnasium signing up warm bodies for their get-out-the-vote drive. Time-filling local Democrats took the stage to ask, repeatedly, for the ambitious to sign up for three electioneering shifts.

McAuliffe arrived only after Herring, Sen. Mark Warner, and local congressman Gerry Connolly gave their own speeches lighting into the radicalism of Cuccinelli, Obenshain, and the accidental lieutenant governor candidate/grifter E.W. Jackson. (Connolly stuck to a script about the GOP ticket; Rep. Frank Wolf, who appeared at the Cuccinelli rally, led off with an update into the Benghazi investigation, encouraging people to watch last Sunday’s 60 Minutes piece.) Cuccinelli had sort of riffed on an open mic; McAuliffe squared his shoulders and, in his blaring and unaltered Syracuse, N.Y., patois, went through an exhaustive list of Cuccinelli’s crimes against moderation, from his opposition to light rail—“isn’t it time we got cars off the roads and folks into mass transit?”—to his entitlement philosophies.

“He actually called Medicaid, quote, outright welfare,” said McAuliffe, “It’s similar to his view of Medicare and Social Security, which he said were created by bad politicians to, quote, make people dependent on government.” McAuliffe’s mother took Social Security. “She’s paid into Social Security her entire life—she’s not dependent on the government!”

Halfway through this speech, the Washington Post released its final poll on the governor’s race. In the back of the room, staffers with the campaign and the Democratic Governors Association flicked through the numbers on their smartphones. All good—McAuliffe up 12, Herring up 3, Cuccinelli’s negative rating in the high 50s as McAuliffe’s positives went up. Danny Kanner, a DGA spokesman who had just sent out a release about Paul “bringing the crazy” for Cuccinelli, told of how the party would frame Jindal when he came to the state. “He was the one governor who backed the shutdown!” said Kanner.

The speeches ran on. Clinton took 25 minutes to walk the crowd through the ongoing economic crisis, Cuccinelli’s suit against climate change scientist Michael Mann, and the risk of higher Republican turnout. “The enduring virtue of [Cuccinelli’s] approach is that everyone who agrees with him will vote,” said Clinton. “Are you absolutely sure that everybody in this crowd is going to vote? How will you feel if he’s ahead in the polls and people didn’t show up? That’s what happened in Colorado in this recent recall election.”

Duly frightened, the Democrats wrapped up the rally and headed back to their cars. On the way out I ran into Jeff Barnett, a Democrat who’d run against Frank Wolf in the bleak 2010 election. He wondered if a Cuccinelli loss would tell conservatives that they needed to tone it down. He worried that they wouldn’t; they were always “fighting the last war” and saying the party was simply not conservative enough.

“You send a bunch of boys over the top,” said Barnett. “They get mowed down. So you send in another wave of them. They get mowed down. You try again. It’s Passchendaele on steroids.”