How This Ends

It looks bleak. But if you close your eyes and dream, this is how the two sides can end this political deadlock—at least for now.

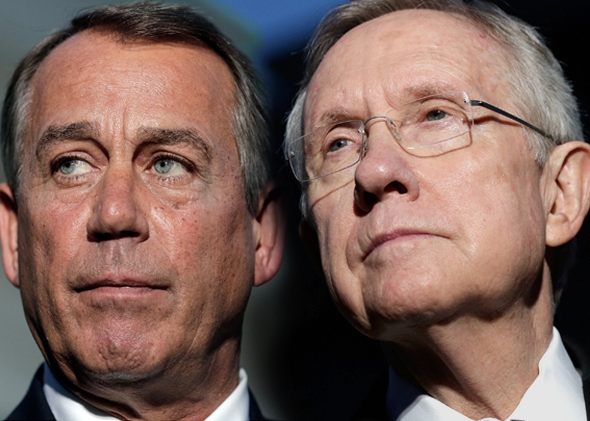

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Getty (2)

Listen to John Dickerson and David Plotz discuss the latest shutdown news.

Have we reached peak bleak in Washington? It feels like it when just about the only thing you hear is Republicans and Democrats making bigger claims about how they won’t blink. But let's engage for a moment in some tiny bit of optimism. What if we close our eyes and listen to that thin slice of the reporting that points a way out of this mess?

We know what a bad debt limit negotiation looks like between these two sides—that was the 2011 mess. But there's actually a closer example of what a more pleasant debt limit negotiation looks like—that's the debt limit increase that passed in January 2013.

In that deal, House Republicans voted to increase the debt limit with a side agreement that bound the Senate to passing a budget or lose their paychecks. Because everything these days must have a hashtag, GOP leaders appeared before a large sign reading #nobudgetnopay.

The deal met the president’s requirement that the debt limit be increased without conditions. It also allowed House Republicans to get what they wanted—something they could point to that showed their constituents that they had held the line and made the Senate get tough on government spending. House Speaker John Boehner only lost 33 of his House Republicans in that debt limit vote. It passed with the help of Democrats but also a majority of the Republican conference.

In retrospect, this deal shows a quaint faith in the budget process that has since gone kaput and landed us in this current fix. The Senate came up with a budget, but Republicans did not want to name conferees to hash out the differences. (They said doing so would be pointless because both sides were too far apart.)The Senate did not consider any appropriations bills on the floor and the House only some of them.

The failure of #nobudgetnopay to do much of anything to improve the underlying budget process is just one of the hurdles to duplicating that deal now. But we're trying to be optimistic, so keep your eyes closed and let's continue our story.

Building on the January 2013 deal, the solution to the current impasse would be a supercharged #nobudgetnopay. The House would pass a “clean” debt limit increase and clean continuing resolution to keep government funded, which is what the president wants. Then there would be a side agreement cooked up by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and House Speaker Boehner that would include something that Republicans want. That agreement would name budget conferees to debate the big issues of spending, taxes, entitlements, and economic growth, and it would include some guarantee—probably in the form of a stick—to make sure the conferees did their work.

Update, Oct. 8, 2013 5:15 p.m.: The president in his Tuesday afternoon press conference said he would support such a two-part agreement to “reopen the government [and] extend the debt ceiling. If they can't do it for a long time, do it for the period of time in which these negotiations are taking place …They can attach some process to that that gives them some certainty that in fact the things they're concerned about will be topics of negotiation, if my word's not good enough… If they want to specify all the items that they think need to be a topic of conversation, happy to do it. If they want to say, 'You know, part of that process is we're going to go through line by line all the aspects of the president's healthcare plan that we don't like, and we want the president to answer for those things,' I'm happy to sit down with them for as many hours as they want. I won't let them gut a law that is going to make sure tens of millions of people actually get health care, but I'm happy to talk about it.”

The stick would have to be more than just holding members’ paychecks because the stakes are higher now. Such pain mechanisms used to be considered a joke, but the no budget/no pay gimmick worked—the Senate did pass a budget after all. Sen. Rob Portman has a bill intended to end dysfunction in the budget process by steadily decreasing funding if there is no budget—a version of that scheme might be adapted to help members focus or face cuts to popular programs. Perhaps a version of that could be bolted on to this side agreement. Or, the debt limit increase could be of short duration to help focus the discussions.

This may sound familiar. It sounds like a supercommittee. That's right. There are only so many ways to construct these can-kicking, exit-ramp exercises. Perhaps the group named to follow up on this side agreement could be called the This-Time-We-Mean-it Committee.

Both sides need an escape hatch. When Boehner has told members he won’t allow a breach of the debt limit, this is the kind of jerry-rigged deal he's envisioning. Such an agreement would also allow President Obama to stand firm on his position that he won't negotiate, but it also rescues him from the potential downside of looking like he’s refusing to act during a crisis that could cripple the economy. In return, House Republicans could tell their supporters that they earned a real chance at future reductions in government spending.

Would this work for Boehner? There would be a revolt from his “Hell No” caucus. But they get that name because we can anticipate their defiance to any possible deal the president would actually sign. Boehner lost 33 of these Republicans in January after the last deal. He'll probably lose well more than that with this gambit. He just doesn't want to lose the majority of his conference. To lose that many more would mean chaos and that he'd given away too much to Democrats.

To keep Republican defections in the House in check, Boehner will remind them what they have already won. Topping the list is the fact that lower spending levels—the cuts mandated by sequestration—are already guaranteed. These cuts are far below what Democrats have requested in the past. The newly fashioned side agreement will also have to include something Boehner can sell as an inroad against the growth of entitlement spending. The House Republicans will suggest something that’s already in the president's budget: Medicare-means testing and changing the inflation formula for cost of living adjustments in Medicare, often referred to as chained CPI. Democrats won’t like this, and there will be a big dustup. The White House has said repeatedly that those offers in the president's budget were contingent on Republicans agreeing to higher taxes. But if this fantasy ever gets this far, it might take on a certain kind of weight of progress. It’ll be hard to imagine defaulting on the debt over the details of an agreement about whether to discuss entitlement reforms. (If this fantasy gets this far, you’re also going to be buying your son that unicorn.)

The fight over a side agreement will look a lot like negotiating, so every once and a while the White House and Democrats will have to remind everyone that they're not negotiating over the debt limit. (That’s important because the president has drawn his line in the sand so far as to even bar syllables about the debt ceiling.) Talking about a side agreement to a bigger deal should not be mistaken for a solution to any fundamental problems, but rather a de-escalation of the mutually assured destruction that comes with a debt limit breach. With some remedies, it's possible to say that the pain was bad but at least the disease was eradicated. Not so in this case. The underlying condition will still persist, which means if there is an agreement, it will contain the seeds of grievance for the next showdown.

Will this happen? Sen. Reid has said that he would name budget conferees once the debt limit issue is solved. That's a tiny start, but there are lots of reasons this could fail, including that agreeing to sit down at a table is probably all Reid is likely to accept. And the politics of the shutdown so far offer no reason for Democrats to deal. In a recent Washington Post poll, 70 percent disapprove of the way Republicans are handling the budget impasse. But absent anything more, Boehner may be helpless to move his members toward a deal.

Another problem with this scenario is that both sides will have to let the other side have its fiction. Each side must be able to pretend they got a win, and let the other side do the same. That may be asking too much in Washington these days. There was a time when you could assume that it was always darkest before dawn. But now Sen. John McCain's joke seems more apt: Sometimes it’s darkest before it’s totally black.