If you live in Washington, D.C., long enough, you will inevitably get interviewed about someone you know who wants a security clearance. I’ve done these interviews about a dozen times over the past 20 years, for friends, neighbors, or former colleagues. An investigator shows up at your house and asks a lot of questions based on a questionnaire the friend has filled out. Afterward the friend under scrutiny will sometimes call, always worried about the same thing (besides the college pot smoking): What happens when he or she tells the truth about having seen a psychiatrist or taken antidepressants?

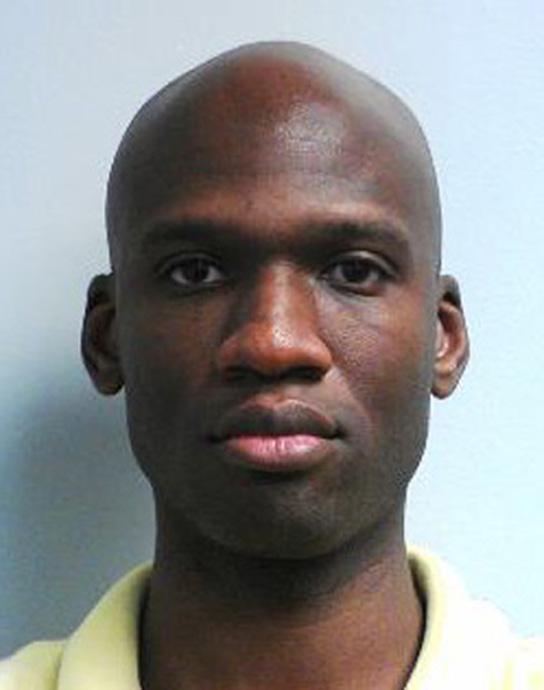

The Defense Department is vigilant about mental instability for obvious reasons, and the Washington Navy Yard shooting is likely to make it more so. The central concern now is how shooter Aaron Alexis, who was discharged from the Navy and has a history of bizarre and paranoid behavior and two firearms-related arrests, could have held on to his “secret” clearance, which is a level below “top secret.” Four U.S. senators have already called for an investigation into the clearance process. Surely the investigation will uncover gaps in the system and places where it could be tightened, especially when it comes to outside contractors. But it would be a shame if the end result was that people seeking a security clearance who have mental health issues become less likely to get the help they need because they don’t want to leave evidence of seeking treatment that could bar them.

A 2008 RAND survey asked service members why they don’t seek mental health care. The survey was aimed at figuring out why more service members returning from Iraq and Afghanistan don’t get help, even though about a third are thought to have some kind of post-traumatic stress disorder, severe depression, or traumatic brain injury. One of the top five reasons was “I could be denied a security clearance.” Another was “it could harm my career,” and a third was “my co-workers would have less confidence in me if they found out.”

The Army Central Clearance Facility has insisted that clearances are not often denied for mental health reasons. The official statistic is reassuring: an average of four cases per year, or less than one-quarter of 1 percent of cases. (The main reasons for denial are credit card or mortgage debt, which is thought to make someone to vulnerable to bribes.) But among military personnel, the stigma around getting mental health care lingers. (Think of Carrie Mathison on Homeland, sneaking her antipsychotics.) As Dr. S. Ward Casscells, assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, explained in a DOD memo on mental health, “People are afraid they are going to lose friends. They’re afraid they’re gong to lose their chance at promotion. [Or that] if you show weakness will you be a good leader? Will people follow? Or will you be seen as someone who is out to just get a desk job?”

After the RAND survey, the DOD made an important change to the security clearance questionnaire to dispel the continuing stigma. Question 21 used to read: “In the last 7 years, have you consulted with a mental health professional or consulted with another health care provider about a mental health condition?” Now the question is surrounded by clarifications, caveats, and exceptions:

Mental health counseling in and of itself is not a reason to revoke or deny a clearance.

In the last 7 years, have you consulted with a health care professional regarding an emotional or mental health condition or were you hospitalized for such a condition?

Answer “No” if the counseling was for any of the following reasons and was not court-ordered:

1) strictly marital, family, grief not related to violence by you; or

2) strictly related to adjustments form service in a military combat environment.

If you answered “Yes”, indicate who conducted the treatment and/or counseling, provide the following information, and sign the Authorization for Release of Medical Information Pursuant to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Alexis underwent a background check by the Office of Personnel Management in 2007. He got his secret clearance in 2008 when he was a Navy reservist, to last 10 years. It’s unclear what he reported on his mental health then or whether he avoided being treated for fear he would be denied clearance. Either way, there are other places the process could have been tightened up in order to flag him—by looking at his Navy discharge records or police arrests. None of them require the DOD to dial back on its newly enlightened stance on mental health. As Marc Frey, a former senior adviser at the Department of Homeland Security told the Washington Post, “Just because you’re depressed doesn’t mean you’re going to sell secrets to the Iranians.”