When they woke up on Tuesday, most members of the Senate were fixing to go nuclear. For the fourth time since 2005, the majority party had responded to filibusters of presidential nominees by threatening to end such filibusters; for the first time, no one doubted that the majority had the votes to do it. There would be an 11 a.m. vote on Richard Cordray’s nomination to lead the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau. If he was filibustered, the Enola Gay was circling overhead.

All of a sudden, comity—that terrific homonym of “comedy,” the word senators always have to over-enunciate—broke out like sunshine through a cottage window. Late-night and early-morning negotiations between Sens. John McCain, and Chuck Schumer produced a compromise. Sen. Lindsey Graham told reporters he would take a “leap of faith” and vote for Cordray. Shortly before 11 a.m., Sen. Harry Reid announced a deal that would let the nominees get their votes.

“As of this morning, I thought there was going to have to be a vote,” said Sen. Carl Levin, one of the very few Democratic hold-outs on the nuclear option. He walked into the Cordray vote, cheerily admitting that the crisis was over.

No thanks to him, the Democrats completely routed the GOP. The credible threat of a scaled-down filibuster was enough to move Republicans away from positions they’d held since 2009. Forty-three of them had pledged not to move on Cordray unless the CFPB was reformed in some ways they wanted; one-third of them caved. Republicans had been holding up Obama nominees to the National Labor Relations Board since 2010, and now they were agreeing to trade two current Democratic nominees for two new ones, pledging to confirm the replacements.

On the right, the scale of the loss was felt immediately. It could only be interpreted with sickness or with silence. “Senate GOP caves again,” tweeted the table-banging radio host Mark Levin. The Club for Growth refused to comment. Republican attrition had been quite effective in gumming up agencies, for quite a long time. Now, Republicans weren’t even getting meaningful concessions. There were “no structural changes” in how the CFPB would work, according to the deal-friendly Sen. Bob Corker.

Democrats had sacrificed Richard Griffin and Sharon Block, the two NLRB members serving thanks to recess appointments that a D.C. circuit panel later deemed illegal. In return, according to Sen. Lindsey Graham, the majority party was “talking about Craig Becker.” Becker was the first NLRB nominee that the GOP had filibustered. Rush Limbaugh had called him a communist.

“Now you might have the return of Becker—you could make it a movie,” said Graham with a dark laugh. “I think the NLRB needs to operate. I get that. The problem with how the president picked these two guys went far deeper than any problem with the NLRB.”

Sure, Republicans didn’t like the recess appointments, but they liked his NLRB appointees even less. Right after he voted for Cordray, Graham tweeted that “NLRB is a four-letter word” in South Carolina. What had Republicans won, really, in the compromise?

“We’ve avoided going from 12 percent to 4 percent,” said Graham, referring to Congress’s job approval numbers. “We avoided going into single digits.”

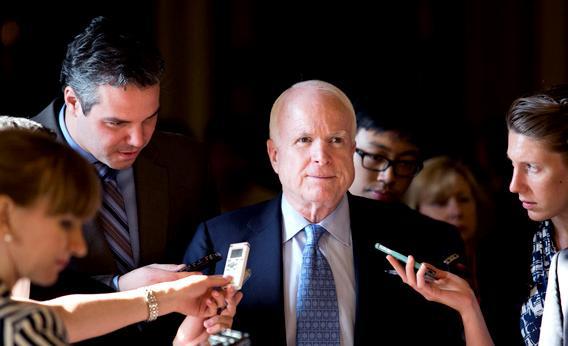

That was a fairly common take on the deal and its upside for Republicans. “Look, we see the polling numbers,” said Sen. John McCain. “Ten percent approval of Congress. Members of Congress want to work more together and get things done for the American people. We appreciate approval, obviously. That’s what politicians largely are about.”

He was describing the limits of an obstruction strategy. Reid’s new push for a weakened filibuster had occurred in stages, after each successful Republican stymieing of a Democratic nominee. In the days before this deal, he bemoaned that Republicans had filibustered Chuck Hagel—“a war hero”—and that dying New Jersey Sen. Frank Lautenberg had been summoned, “literally from his deathbed,” to vote for a bill that Republicans filibustered anyway. His goal was to put some distance between Democrats in Congress and Republicans, and play off an existing public impression that the Republicans were responsible for whatever they hated about Washington.

The public was very present in the Senate on Tuesday. As Republicans met to huddle over the deal in a room named after the late South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond, a steady flow of tourists moved between them and reporters. After McCain spent a few minutes talking about how senators “looked into the abyss and stepped back,” and started to walk back to vote, one tourist whose legs had been amputated stopped him.

“You’re a hero,” said the tourist.

“Thank you,” said McCain. He shook hands with the tourist’s family and patted the youngest member on the shoulder. “Nice to see you all! How you doin’, pal?” Then he returned his attention to the reporters, telling them that “elections have consequences” and that he maintained a good relationship with Sen. Reid.

No wonder the right was quiet. Its strategy, all year, has been to raise hell about Obama’s initiatives and nominees and loudly celebrate when the filibuster blocks them. After a filibuster thwarted the watered down post-Sandy Hook gun bill, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz told activists that the senators who stood on “principle” had beaten the “squishes.” Republicans can still use filibusters to humiliate the Democrats. But this week saw a late-night Kumbaya meeting that actually worked, a dangerous precedent for the block-everything strategy. Sen. Chuck Schumer was just one of many senators to call for more bipartisan meetings.

“We started to do more with the inner sanctum,” he said. “We go on boat rides occasionally, together. To do it more often, one way or another—I think that’s the overwhelming consensus.”