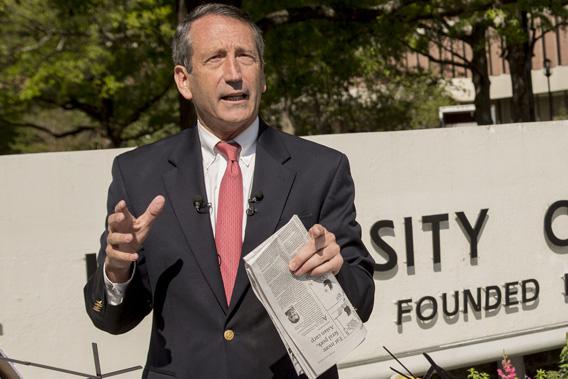

MT. PLEASANT, S.C.–When people recognize Mark Sanford—this happens extraordinarily often in South Carolina—he notices. He notices the contractor waiting in his car, or the woman shopping for lettuce, or the student who looks up from his phone with an oh-it’s-that-guy expression. At a tire store in this Charleston suburb, part of the 1st Congressional District that Sanford wants to represent, he makes the circuit of a waiting room, issuing his icebreaker again and again.=

“Can I be rude,” he asks, “and say hello?”

When a voter lifts a camera phone to take a photo, Sanford knows, and he spins around to take charge. “If you’re going to take a picture,” he says, “can I be in it?” If this person is merely a gawker, visiting from Florida or Illinois, Sanford smiles and hands over his business card—“if you have any family in the district, they can call me.” If he might know one of Sanford’s sons, the candidate whips out his white iPhone and calls his son for an impromptu chat. If the person makes a joke, Sanford bends his knees and guffaws at the funniest thing he’s ever heard.

This was how Sanford spent the final weekend of his campaign for Congress, a meet-cute scene repeated ad infinitum across the district. He’s done this for nearly five months, and it’s gotten easier—instant public affirmation and forgiveness for his trespasses in real time. To win back the congressional seat he held in the 1990s, to be a distinguished gentleman who can once again decry the federal debt and the welfare state, he must single-handedly win over the people who—let’s be honest—don’t want to elect a Democrat unless they’re desperate. So he keeps talking.

“It’s a blessing,” said Sanford on Saturday, as he walked his home turf in Beaufort, S.C. “I’ve been to a place in life wherein people didn’t want to get pictures of me. It was a very quiet spot. I spent a year on our family farm in northern Beaufort county, which is half an hour up the road—a quite incredibly introspective year.”

Beaufort had been taken over in celebration of Candice Glover, an American Idol contestant who’d made it to the final three, thus earning a taped-for-TV parade and concert. Sanford adapted immediately, posing next to a pro-Candice T-Shirt (“The Low Country’s Idol”) and greeting people with a chipper “Happy Candice Day!” Sanford never appreciated the grip-and-grab-and-grip-some-more side of politics until he’d walked away from it all on the “Appalachian Trail.”

“If you’ve been in politics,” he said, “you have people who want to take their picture with you, but it was very different. I love people, I’ve always loved people, but it was the kind of thing you had to do.” But now: “I was at a thing with my boys. We were trying to get into a football game. It was one of those things where it was incredibly elongated by people who wanted to take pictures.” Sanford grins at the memory of his bored, irritated kids. “I said guys, you don’t get it. This is an incredible blessing.”

Many voters here—most of them, possibly—are in the mood to bless him. Mitt Romney won this district by 18 points, but that might even undersell how Republican it is because African-Americans who voted for Barack Obama are harder to turn out in any special election.

Elizabeth Colbert Busch, inevitably referred to in national news as “the sister of TV comedian Stephen Colbert,” is a business development guru who’d once donated to Sanford. If you’re ashamed of Sanford, she’s your tolerable alternative. Her radio ad played incessantly on conservative talk radio chides Sanford for voting against dredging the port of Charleston because… well, you know.

Mark Sanford had a better use for our tax dollars. He used taxpayer money to be with his mistress in Argentina.

Colbert Busch said this to Sanford’s face, almost—in their sole debate she reminded everyone that his Argentina trip was “personal.” Nobody else will get in his face about it, not even after his ex-wife Jenny filed a trespassing complaint against him, not even after voters learned Sanford would have to be in court two days after the election. When an NBC producer asked him about this, Sanford walked from female voter to female voter to “try to find a woman who doesn’t like me.” When I caught up to him in Beaufort, he was still bristling.

“The NBC gal who was with us earlier,” he said, “she—”

Sanford was cut short, because a real-life female voter was interrupting him, asking for a photo. For three minutes I waited as Sanford posed and small-talked and posed some more. Eleven different groups of people, mostly women, took home Sanford snapshots. The only dissonance came from a woman who quickly ruined the picture by making “bunny ears” over Sanford’s head and sprinting away.

“The NBC affiliate comes down from Washington,” said Sanford, finally, “and their angle is, you know—you’ve got a woman problem. I say—What? Come with me. Come with me for the day.” He laughed as he walked over to meet some soldiers walking around Beaufort in fatigues. “The national media decide what their story is.”

The real story, as designed by the Sanford campaign, is this: Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi is trying to buy the seat. Colbert Busch’s affable promise to work with both sides is a cover story. The message is scrawled on wooden planks that dot the roads from Charleston to Beaufort, in black spray paint—“Sanford Saves Tax $” and “Sanford: Boeing = Jobs” and “Say No to Pelosi’s $1 Million.” At Molly Darcy’s, a Charleston bar where Sanford volunteers congregate after work, the first sign is leaned against a fence, partially obscured, making it read simply, religiously, “Sanford Saves.” The handwriting is as about as crisp as the ones held by cows on those Chick-fil-A “Eat Mor Chikin” ads. They’re supposed to recast the Sanford campaign as a grass-roots crusade, and they work.

“We gotta stop Pelosi,” said Wayne Baker, a retired propane salesman, when he got his chance to meet Sanford in Beaufort. “Hey, I’ve been through a divorce. Sometimes it works, sometimes it don’t. If it don’t, you move on, you make yourself a better person. He did his thing. He didn’t hide it—he came out in public. The way he did that, I think people got more trust in him.”

Baker looks at my notebook and tape recorder. “You’re in the media, so I’m gonna say some things. Do you know why some of the best people don’t run? They got a background. They got stones in the backyard you can dig up. But he’s already come out with his girlfriend. You can respect that.”

Sanford ended his Beaufort trip on the third floor of an office building, on a pleasant porch overlooking the Candice Glover parade. A Republican donor, who keeps intermittently forgetting that I’m a reporter and thanking me for “everything you’re doing for the governor,” whips out an iPhone and shows me the sort of thing that’s “winning this thing in social media.” It’s just a picture of Nancy Pelosi in Joker makeup. Sanford hangs onto every fiber connecting Colbert Busch to national Democrats, from her union support to the donations coming in through the progressive online donation bundling site, ActBlue. “Somebody told me that Elizabeth Warren, in her race, received half of her funding from ActBlue,” Sanford informs reporters on Monday. “I don’t know if that’s true or not, I just heard it.” The point: “Be wherever you are. Don’t be stealthy.”

In other states and campaigns, Democrats like Colbert Busch have threaded the needle. They’re not like those other Democrats, the liberals, the ones you can’t trust. Colbert Busch attempts to do this by inserting some reference to business experience in whichever part of the sentence it may be grammatical. Sanford’s omnipresent radio ad hits the Democrat for theoretically favoring “Obamacare, economic stimulus, raising the debt ceiling.” That’s the kind of district this is—a place where being willing to raise the debt ceiling is a threat to decent people. On Monday, after she finishes a friendly visit to a black barbershop in the north Charleston suburbs, I ask Colbert Busch under what circumstances she’d raise the thing.

“I’m a businesswoman, OK?” she says. “Twenty-five years. Before you do anything, before you make any changes, you go in—it’s very basic, here’s my operations cost, here’s how much revenue I can bring in. If my costs are too high, I have too much waste, I’m doing duplicative work, I need to address this first. Until that gets addressed you can’t deal with anything else.” Does that mean no debt ceiling hike without spending cuts? Colbert Busch holds up her hands, as if she’s weighing bushels on a scale. “You have to get your cost under control, right? You have to get your fiscal house in order. At the same time you’re cutting your waste, you’re watching your spending, you prioritize your dollars over”—left hand—“here. What happens when you’re prioritizing your investment? You bring this”—right hand—“under control.”

Sanford’s answer is simpler: He doesn’t want to raise it. On Monday, he stumps in more random, friendly locations with Republicans who’ve endorsed him. At a diner, former Gov. James Edwards warns that a loss here might lead to the loss of the Republican House, which would let President Obama become “a dictator.” State Rep. Chip Limehouse, one of the Republicans who lost the primary to Sanford, nods along.

“It’s a battle for the soul of the country,” he says. “If we lose the House, we’ll lose America.”

“Then it’s all over,” says Edwards.

Nearby, Sanford stands in front of TV cameras and talks about the polling that shows him, finally, inching ahead of Colbert Busch. People made fun of him when he “debated” a cardboard cut-out of Nancy Pelosi. But had it worked?

“You know,” says Sanford, grinning, “a lot of my friends in the local media circles said I actually won that debate.”