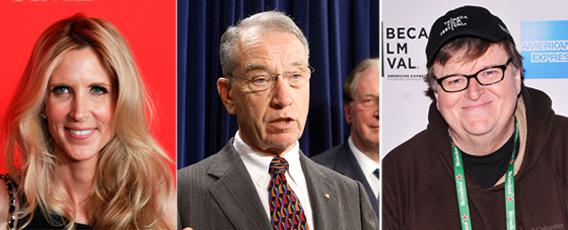

As the manhunt for the remaining Boston bombing suspect unfolded, partisans took to Twitter. Watching them scramble to come up with an easy political explanation for the events was like watching a 1950s switchboard operator. Too few guns? No, wait, soft on immigration. No, Islamic radicalism. These conclusions weren’t being drawn based on facts, but rather existing arguments and political agendas into which the skinniest fact or rumor could be fit. Sen. Chuck Grassley suggested at a Senate hearing on immigration that the incident meant we needed a thorough investigation of the loopholes in the immigration system. What evidence was there that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and Tamerlan Tsarnaev had exploited loopholes at the time of Grassley’s claim? None.

We need more restraint and less wild guessing. Free-flowing debate in the search for meaning is a part of these moments and a part of the human condition, but what I’m talking about is using tragedy for evidence shopping. That people reach immediately for their pet political theory at moments like this highlights what’s wrong with a lot of political debate. But perhaps this moment also offers a useful sorting technique. If you can’t shut up now, when either reason, decency, or good taste requires it, you disqualify yourself from the conversation in calmer times.

If you’re going to reason with someone over a complicated issue, you’ve got to have the expectation that they are going to leave a little window open to persuasion. There can’t be much of a debate—or even conversation—if they are in such a state of siege that they instinctively dismiss everything you say or take every new fact and mindlessly mold it to their purpose. Through this narrow portal you might be able to squeeze your salient point and come to some understanding about a complicated issue.

Political debate about facts is fine. When the White House puts out a picture of the president in the situation room, it’s fine to point out that it’s propaganda they never put out on Benghazi. But a person who uses tragedy as new evidence in an existing political fight is probably incapable of keeping this window open. They can’t pause to honor the solemnity of a moment of tragedy or wait until the facts come in, which means that the facts never really mattered much to them at all. These partisans are ever on alert to advance their relentless claim—whatever it is. Michael Moore immediately fingered Tea Party types after the bombing. In the hours after attack, when authorities questioned a man of Saudi dissent (who was later released), Rep. Steve King tied it to the comprehensive immigration reform he opposes. Nate Bell, an Arkansas state lawmaker, tweeted, “I wonder how many Boston liberals spent the night cowering in their homes wishing they had an AR-15 with a hi-capacity magazine? #2A” There was lots of this from partisans on both sides on Twitter.

In the wake of the Boston bombing, a lot of smart commentators suggested we follow the advice of the World War II British poster: Keep Calm and Carry On. Since we seem predisposed to misinterpret events upon first hearing, perhaps jumping to conclusions is the most natural way for people to “carry on.” Maybe, but it is not an example of calmness; it’s an example of panic—or even worse, shameless opportunism.

When someone makes a tasteless joke in proximity to a tragedy, we say it’s too soon. There should be a disqualifying equivalent for those who declare political conclusions too fast.

In these fast-moving times when the only thing that is certain is that the first piece of news has repeatedly been wrong, perhaps those lawmakers and pundits who want to be part of the final conversation should (paraphrasing Mike Monteiro) follow the Quaker rule: Be meaningful or be quiet.