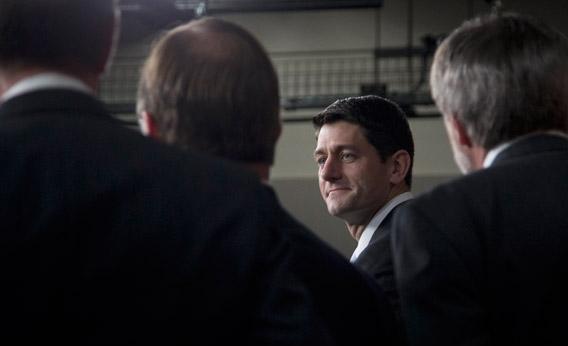

Shortly after 10:30 a.m., Tuesday Rep. Paul Ryan and the Republican members of his House Budget Committee entered the TV studio and took their places. They positioned themselves behind the economic guru of the party, holding white and green copies of The Path to Prosperity as tight as hymnals.

“What we have here,” said Ryan, “is a budget that balances the budget. A path to prosperity with a responsible balanced budget. We believe that we owe the American people a balanced budget. And for the third straight year, we’ve delivered it. In fact, we’ve balanced this budget in just 10 years. This is a document, a plan that balances the budget in just 10 years.”

In 25 seconds, Ryan had uttered some tense of the word “balance” five times. This was master-class message discipline, telegraphed weeks in advance. In the middle of January, Ryan had sold House Republicans on a three-part punt of the coming fiscal crises, climaxing with a budget that would balance in 10 years. His previous budgets took 25 years to come into balance. Some Republicans did their own math and panicked: Would Ryan be forced to expand his Medicare “premium support” plan to hit more seniors?

He wouldn’t. For all of its mystic, wonkish charms, a budget resolution doesn’t have to be very specific. Ryan eliminated the deficit in 2023 by counting new revenue from the “fiscal cliff” tax hikes, repealing Obamacare, restoring money that had been “raided” from Medicare, and cutting social programs by as much as 50 percent. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s math, he would balance the budget and Democrats wouldn’t.

As Ryan talked, the National Republican Congressional Committee issued cloned press releases to brag about this difference. “Will [New Hampshire Rep. Anne] Kuster Stand Up for a Balanced Budget?” they asked in one email. In another: “It’s time for [New York Rep.] Tim Bishop to step up to the plate and demand that SOMEONE in his party produce a balanced budget.”

It’s good, clean hit. Senate Democrats haven’t passed a budget resolution since 2009. (They have, obviously, funded the government. Remember, budgets are more about statements of principle than making numbers add up in real time.) On Wednesday, Washington Sen. Patty Murray will release a budget, which will include a rumored 1-1 ratio of tax hikes to spending cuts, but won’t balance. The White House has never produced a balanced budget. It’s hinting at a plan in which “the ratio of debt to GDP is below 3 percent”—stable, but not balanced.

Why do Democrats keep tumbling backward into this trap? Because they don’t think it’s a trap. Voters don’t punish them for failing to balance the budget. In 2012, Mitt Romney won voters who called “the deficit” the “most important issue” by a 2-1 landslide. And yet Romney’s eating birthday cupcakes in California somewhere, and Paul Ryan is stuck in the House, reintroducing his old budgets. Investors don’t punish the Democrats, either. In 2011, when Standard & Poors downgraded America’s debt rating, the agency fretted for a plan that fixed “the government’s medium-term debt dynamics.” It didn’t cry out for a balanced budget. And then everybody stopped paying attention to S&P.

Think back to the origins of this Ryan budget. Why does it balance in 10 years, not 25? Because back in January, at the House Republican retreat, it seemed like the sort of thing that could get the feral members in line. “This looks like a concession to the internal dynamics of the [Republican] conference,” says National Review columnist Ramesh Ponnuru. “It doesn’t make as much sense in the broader context of public opinion.”

Ponnuru should know; he was one of the speakers at that retreat. He’s happy with much of the new Ryan budget—“it’s great that they’re still standing for Medicare premium support”—but wonders whether they focused on the wrong numbers. Why be so specific about when the budget will balance, but not about how? The Ryan plan collapses the tax code into two “pro-growth” rates, 10 percent and 25 percent, with no change to expected revenue. At today’s press conference, Ryan was asked whether he’d get those numbers by closing loopholes that middle-income people crave—the mortgage tax deduction, for example. Ryan said that the Ways and Means Committee would hold hearings to figure this out, but it might be painless. “You can actually plug loopholes and subject more of a higher-earner’s income to taxes with a lower tax rate,” he said.

Why leave it so vague? “I don’t think there’s good argument for being specific about the rates and unspecific about the tax base,” says Ponnuru. “They’ve left themselves open to the argument that they are delivering a specific valuable promise to rich people. If you’re making $2 million, and your top rate falls from 39.6 percent to 25 percent, you’re going to be saving a lot of money.”

And this is how Democrats have always defeated the “balanced budget” cause. In 1995, when a balanced budget amendment was close to victory in the Senate, Democrats warned that mandatory balance would mean biting hard into Social Security. In 2013, a new Senate Republican version of the BBA has been introduced, and forgotten. Republican strategists admit that “balanced budgets” are a “70 percent issue”—supermajority support when voters hear about them—but that the details of possible cuts remain horrifically unpopular. Republicans who aren’t yoked to the party’s daily messaging don’t see the benefit of making sure every idea has a nice CBO score.

“What I would have advised to Romney, if Romney won, was something that immediately helped the economy,” says Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul. “I’d pass one bill that cuts the corporate income tax rate in half. I would have started there. I wouldn’t have worried about whether it was revenue neutral, or what anyone says.”

And Democrats don’t sound worried about their “unbalanced” budget. I asked Alaska Sen. Mark Begich, who’s up for re-election next year, whether he was comfortable with a budget that didn’t balance buy a certain date. “I don’t worry about those things,” he said. “We’re working towards a balanced budget.” Maine Sen. Angus King, an independent elected last year, made the same distinction. “The important thing is we’re on a sustainable path toward a balanced budget,” he said, “while at the same time not crippling the economy.”

King has slain the “unbalanced” dragon before. When he ran for Senate, Republican-aligned groups attacked him for his record as governor from 1995 to 2003. “When King left office,” warned the narrator in one Chamber of Commerce ad, “he left Maine with a $1 billion budget shortfall.” None of this stopped King from winning a three-way race, by 22 points. The Balanced Budget God, so compelling to Republican voters, isn’t so compelling for anyone else.

“Republicans are missing the vast majority of the American electorate,” says Kellyanne Conway, a pollster who spoke at the GOP retreat. “They’re not job seekers. They’re not job creators. They’re job holders. Focus on them.”