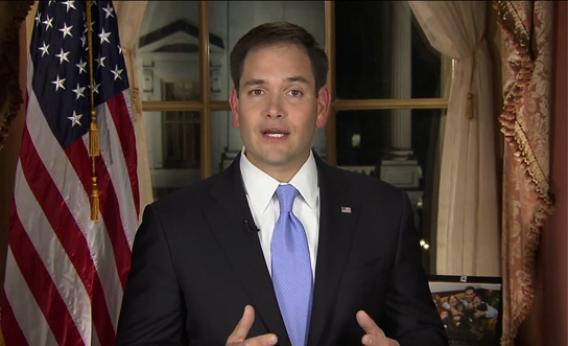

What’s worse for your political ambitions, being labeled a wimp by Newsweek or a savior by Time? Marco Rubio, the freshman senator from Florida, has been stuck with the savior label and it has several disadvantages. It makes allies suspicious, irritates your rivals, and perhaps worst of all: When you’re a savior, people expect you to perform miracles.

After Rubio delivered the Republican response to President Obama’s State of the Union Address, commentators said he had simply mouthed standard GOP talking points. How was he going to expand the Republican electorate by doing that? A particularly damning charge was that he sounded too much like Mitt Romney. As Jonathan Martin pointed out, Rubio’s speech—thick with references to his humble origins and common touch—was designed to send the signal that he was the polar opposite of Mitt Romney.

The story of Rubio, his ambitions, and how they play out is about more than just the fortunes of one charismatic Republican. Rubio is one of the architects of the Republican future. Like Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, Rep. Paul Ryan, and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, his ambitions are linked to his party in a way that is different than figures with greater power like John Boehner and Mitch McConnell. Every day Rubio is taking soundings about what the GOP will allow and what the larger electorate will allow. The risks he takes and the reactions they provoke from his fellow-travelers will tell us something about where the party is headed.

Still, the criticism of Rubio’s State of the Union response asks too much too soon. The GOP is not ready to announce a sweeping new direction, (it may never be ready) and Rubio isn’t in a position to launch a thorough rebranding right now anyway. Even if he was, 10 minutes after the State of the Union would be the wrong time to do it. Still, if Rubio is going to add new energy to the GOP, he’ll have to find a venue where he can make a much more compelling case for the party’s signature principle: the promise and glory of smaller government.

For many conservatives, the criticism of Rubio’s message on Tuesday night is meaningless. The media apply labels in part to then remove them. So build up Rubio and then take him down. It’s meaningless for another reason too: They don’t think the party needs much tinkering. So when Rubio reads from the traditional GOP script it sounds good to them.

Rubio and his team care about this parlor game though. The senator tweeted out a response to the Time cover: “There is only one savior, and it’s not me. #Jesus.” Rubio cares because he buys into the notion that the Republican Party needs to change and he wants to be the voice to lead that change. But a freshman senator can’t just determine what the new direction of the party should be. Smart substance is helpful to the GOP—that is the type of differentiation they need right now, especially when the president’s State of the Union message is the equivalent of an only child’s Christmas list. But Rubio and his party aren’t there yet. The precise amplitude of that new change is still being triangulated—by both Rubio and other Republicans like House Majority Leader Eric Cantor.

Whoever the transformational figure is, he or she is going to have to build a bridge between the old and the new. That requires at least two tasks: challenging orthodoxy and giving special voice to it. If you can sing the song of American exceptionalism and free enterprise in a way that pleases your party base, then you can push the envelope on immigration without fear of being called a RINO or consorting with Karl Rove. Rubio’s task Tuesday night was to sing the Republican anthem. It was a time for team spirit. The party was going up against Obama. The script was pre-written. Plus, Rubio is already clashing with conservatives over his immigration reform plans. To the extent he has other provocative ideas (and he may not), it doesn’t make sense to create more tumult while you’re trying to make rocky progress on immigration.

But here’s where Rubio has work to do. His address wasn’t that thrilling on the signature question at issue: the size of government. It was, like Mitt Romney’s entire campaign, a list of assertions rather than a compelling case about how the middle class benefits from smaller government. There are also policy critiques about Rubio’s vision of smaller government (critics say he was wrong about private investment, the cause of the housing crisis, and other issues), but let’s leave aside policy for the moment. There is one thing that Republicans of any incarnation past or present are going to put at the center of their platform: Smaller is better. Whoever can make the best case for that essential principle wins the day.

Rubio’s case wasn’t that nearly savior-worthy. It affirmed the bounties of the free market, but he spent most of the time explaining why Obama’s big government was bad. An amazing story about the wonders that would flow from smaller government would be more appealing and persuasive. Bromides about unleashing sectors and removing regulations are tired and threadbare. For conservatives, progress flows naturally from smaller government; you don’t have to do a lot of explaining at the Lincoln Day dinners, but Rubio and his party have to do more than convince conservatives. There are people who might distrust government but also rely on it, and there are those who worry that when the government shrinks they won’t share in the new arrangement. Arguments about how big government is bad don’t speak to those fears.

There’s also perhaps a lesson Rubio can take from something Mitt Romney did well. For much of the campaign, Romney portrayed Obama as a guy who cared and was trying to do the right thing but who was just in over his head. The Romney campaign didn’t want to spook those voters who had backed Obama in 2008 but were having second thoughts. No reason to make them feel bad or defensive about their initial decision. But there was another benefit to this approach; it kept the focus on a clash of policies. It suggested you wanted to help the middle class as much as the bleeding heart liberal, you just had a different way of doing it. It also undermined the idea that the GOP attack was driven by bitterness, a siege mentality, or pique. Romney was never able to convey this shared concern for the middle class, but a senator who lives in the same working-class neighborhood he grew up in probably could.

Finally, there is Rubio’s aqua lunge, as Politico’s Martin put it. While it was natural for some performance conservatives to get into a righteous wind about the Twitter traffic making sport of Rubio’s awkward pause to take a drink of water, Rubio was smarter than that. He didn’t turn water into whine, complaining that people were making too much of his emergency gulp. He made sport of the episode, which allowed him to show humility, good spirit, and his light-on-his-feet instincts. It’s a small thing, but those were never words applied to Mitt Romney. That’s a start.