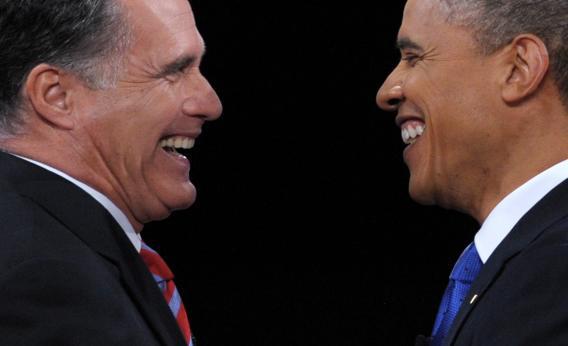

BOCA RATON, Fla.—Halfway through the final presidential debate, after Bob Schieffer asked about negotiations with Iran, Mitt Romney asked the audience to remember something that never happened.

“The president in his campaign four years ago said he would meet with all the world’s worst actors in his first year,” said Romney. “He’d sit down with Chavez and Kim Jong-il, with Castro and President Ahmadinejad of Iran. And I think they looked and thought, well, that’s an unusual honor to receive from the president of the United States. And then the president began what I have called an apology tour.”

Yes, when he was a candidate for the presidency and a suitor for anti-war voters, Barack Obama had pledged to meet a mug’s gallery of dictators “without preconditions.” During the campaign, it became a sort of accidental foreign policy. Then Obama became president, and—apart from one awkward photobomb from Chavez at a meeting of Latin American nations—the meetings never happened. Neither did the “apology tour,” really. It was as if Romney had written down some zingers in 2009 and accidentally brought the wrong notes to the table.

Most of the debate felt that way. On the most ringing foreign-policy questions, on Afghanistan and Iran, Romney blurred the differences between Obama and himself. The “crippling sanctions” on Iran were “absolutely the right thing to do,” and “something I called for five years ago, when I was in Israel, speaking at the Herzliya Conference.” Troops would come home from Afghanistan on basically the same timetable that Obama had drawn, because “the commanders and the generals there are on track to do so.”

Which is what Obama always says. He pointed this out, with relish. “There have been times,” he said, “Governor, frankly, during the course of this campaign, where it sounded like you thought that you’d do the same things we did, but you’d say them louder and somehow that would make a difference.” It rang true.

When Romney wasn’t nudging the debate back to domestic policy (Obama usually went along), he was either congratulating him on tactics or demanding a tougher strategy. The “apology tour,” as Romney finally defined it, meant that Obama “went to the Middle East and you flew to Egypt and to Saudi Arabia and to Turkey and Iraq.” Again, this happened years ago. In the spin room after the debate, as he successfully dodged Triumph the Insult Comic Dog, Romney strategist Eric Fehrnstrom confirmed that Romney wanted to retell voters about “candidate Obama in 2008” and “the Obama we saw in the first 18 months of his administration.”

Obama’s response to this was to look even further into the past. He emptied out his briefing books, asking Romney to explain why he’d switched positions when, as a candidate, he needed to be a critic of the administration. What had proved Obama right? The killing of American enemies who’d been threats for a decade or more. He mentioned Osama Bin Laden six times, and mentioned Muammar Qaddafi twice, shutting down the discussion of Libya by pointing out that its old rulers killed more Americans than had died in Benghazi.

Republicans were unimpressed. “He was using a dramatic name to play on an old fear,” shrugged Rep. Peter King, chairman of the House’s Homeland Security Committee, who’s been calling for the Obama administration to fire U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice over her Benghazi statements. “The fact is, Qaddafi was nullified by Bush. He was not a threat.”

While every post-debate poll called it for Obama, this interplay—the focus on the recent past—was on balance good for the challenger. The CNN poll that gave Obama a 48-40 overall win also asked independents whether they could see Romney as commander-in-chief. By a 62-36 margin, they said yes. Asked that question about Obama, they gave the same margin.

If that number holds, it’ll be because Romney managed to make the “say it louder” argument without getting caught. His description of an anti-terror strategy that didn’t involve apologies made almost no sense. He would rely on the advice of “Arab scholars,” and “interrupt” the “bad guys,” but not go to war. “We don’t want another Iraq,” he said. “We don’t want another Afghanistan. That’s not the right course for us.”

That made Romney sound like he was cold on more military commitments, even as he inflated the military budget. Take this further into the present, and you can attach real missions to it. I asked Sen. Lindsey Graham, the South Carolina Republican who’s become a sort of leader of the hawks, exactly how a Romney presidency might tackle its first problems, starting with Libya.

“The first thing I’d recommend that a President Romney do is go into Libya and help train a national army to de-fang the militias,” he said. There might be different responses in different nations. “In northern Mali, it might be special forces operations.”

Graham framed all of this in a criticism of the last administration, the Bush team. “I remember being told that we didn’t need 160,000 troops. I remember being told it would cost $50 billion.” As we talked, some veterans of the Bush team, like Romney’s senior foreign-policy adviser Dan Senor, walked around spinning for Romney. Why was he confident that these people would get it right—not just perfect hindsight, getting it right on the next crises—if they took power again?

“They eventually readjusted their strategy,” said Graham. “I think they have the lessons of Bush seared into their brains. If I were Romney, I’d tell the American people I won’t be a cowboy, and I won’t be an apologist. I’m gonna be smart.”