As the presidential election heads into its final days, the most important decision strategists in both campaigns are making is where to send the candidate. There is no more precious resource: Every visit initiates a multilevel strategy to capture votes, voter information, and volunteers who can be squeezed for one more hour of effort.

In this final stretch, the size of crowds at rallies can reach into the tens of thousands. The candidate’s pitch is more urgent: What voters choose to do with their ballots will change the course of the nation. But beneath that vast sweeping feeling of history is an intense and focused game of gathering and sifting. To most of us, the attendees at a rally look like an undifferentiated blanket of people, but to those working the political ground game, it is a pixelated assortment of uncollected cellphone numbers, hands to work the phone banks, and sturdy legs to walk neighborhoods. In states with early voting, the people a candidate draws to a rally are fresh meat to be cajoled onto a bus and taken to a polling place. “How about we get in our car, vote early, and bank our votes,” said Sen. Rob Portman Thursday morning in Cincinnati, “so that on Election Day we can make sure other people get out and vote.”

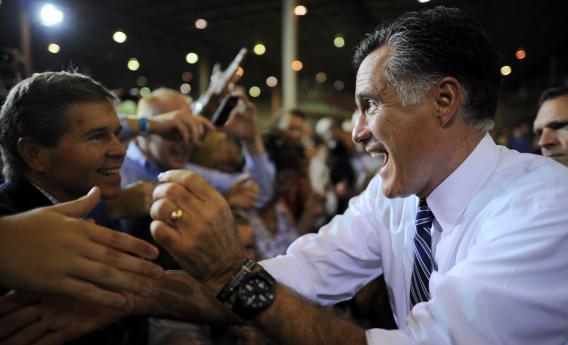

In this process, the candidate is the flypaper. Before Barack Obama or Mitt Romney visit a town, their campaigns email supporters and targeted undecided voters. At a minimum, their teams will obtain a piece of private information, perhaps a cellphone number, that can be used to encourage someone to vote. Even better is if they can score a commitment from someone to vote early. Best of all is if they can obtain a promise from that voter to volunteer for the campaign, thereby adding another foot soldier to the cause.

The ticket to see the candidate is the bait. Voters can get them at the local campaign office. Once inside, a volunteer takes down as much information as possible and tries to secure those commitments for future volunteering. Campaigns are consumed with the idea that individual voters are motivated by community contact. Neighbor-to-neighbor appeals work the best. A campaign outpost in the neighborhood is effective because a voter is handed a ticket by someone who looks like them or shares their experiences. That is why the number of offices in a state can matter. (In Ohio, the Obama team has more than 120; Romney has about 40.) They expand a campaign’s ability to make neighborhood connections.

Every ticket has a code. When you show up and get your ticket scanned, the campaign knows it. Staffers with iPads will stop you to ask for more information like that all important cellphone number. (In the campaign vernacular, the voter is being “caged” for information.) If they don’t convince you to get on the bus or drive to the early voting location after the rally, the campaign will contact you in the next several days. You’re likely to get a phone call from someone who attended the rally and voted, asking you to do the same. When you are trying to gather every possible vote, it is more effective to begin the conversation with I see that we were both at the rally together than with the generic I’m calling in support of candidate X.

But most rallies now are filled with the faithful who are already likely to vote. They represent a different opportunity. They can be used to make voter phone calls and contacts that are crucial in motivating all kinds of voters, though the biggest prize these days are “low propensity voters.” These are people who have intersected with politics at some point and in some way—signing up on that web site or giving that small donation is how they got on one of the party lists—but who aren’t regular participants. These are the voters who take the most work to get to the polls, either because they are lazy, only mildly interested, or because they have complex allegiances. Maybe this resident of Canton voted for Ohio Gov. John Kasich but against his collective bargaining legislation. Both parties want that guy. Republicans know he’s open to their team; Democrats know that he cares about unions.

The Obama and Romney campaigns understand that if they are simply using the early voting period as a time to bank the votes of people who would otherwise have waited in line on Election Day then they are doing it wrong. The team that wins will be the one that grows the size of their vote. For Democrats, this is even more crucial. Polls show the president is doing better with registered voters than with likely voters. Obama needs to erase the distinction, or at least shrink it.

At the Obama rally in Dayton on Tuesday, buses were lined up to take voters to local polling places as soon as the president left the stage. Romney aides kept a careful watch on the polling places in the area to see if there was a noticeable increase in activity. (They naturally say there wasn’t as much as they would have expected; the Obama team claims the early voting in that area has far outstripped the totals from 2008.) If the Romney team did detect a lot of activity after the rally, they could redirect their efforts. They’d make more phone calls into those neighborhoods and surrounding suburbs, they’d send volunteers to knock on more doors, or they’d send a surrogate. If it were serious, they might mark the area with a big red X for a future visit from the candidate himself.

How closely are the campaigns watching these early vote totals? The Romney campaign saw an uptick in votes in Belmont, an Ohio Democratic stronghold, and worried party loyalists were rallying around Obama. They launched an investigation. Using the list the Ohio secretary of state releases each day of early voters, they called some of those who had voted and polled them. It turns out, according to a Republican source, that those voters were coming out to vote against the president and his coal policies.

Finally, when the candidate comes to town it offers an opportunity to broadcast a message to undecided voters who might never attend a rally. “Until he’s commander in chief, he’s persuader in chief,” said one of Romney’s top Ohio lieutenants about the candidate’s visit to the state. Romney’s job is to drive a message in local media that gets through to undecided voters. It is calibrated by looking at the state’s most recent polling numbers so that the message can be aimed at white women or Hispanic voters. “He needs to sound like their neighbor, too,” says one local Obama staffer of the targeted messages fed to the president. “That’s what builds up trust.”

It’s also a chance to push for votes, as Romney did in Cincinnati on Thursday. “I need you to find someone else who might be willing to vote for the other side,” he said. “Go out there and find some people, bring them to the polls. For someone who doesn’t have a ride, get them to the polls.”

As the days dwindle, the campaigns will be forced to make brutal decisions about where they should deploy their candidate. What states are in the greatest need of a visit? Based on last-minute polling data, which portions of a state are more important than others? Could a presidential visit in some cases actually distract the army of volunteers from their last weekend duties of going door-to-door by pulling them to the rally and away from the neighborhoods? Soon some states will start to feel orphaned. Each campaign has enough money to keep buying television ads until the final day. The real test will be deciding whether the candidate comes to town.