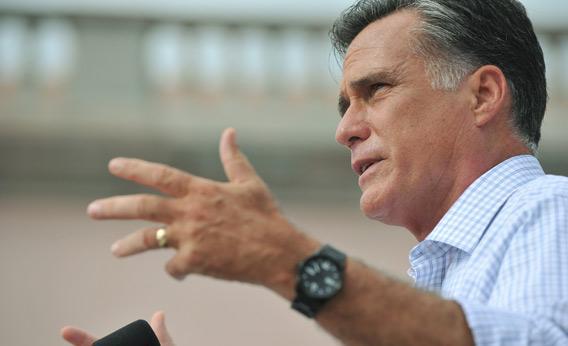

Mitt Romney is a turnaround expert. He says he can turn around the country. But first he must show he can do it with his campaign. When Barack Obama was running for president in 2008, he and his surrogates argued that the way he ran his campaign was a proxy for how he would govern. The one-term senator had to make this case because he had no experience running anything. Romney is pitching himself as the exact opposite: He is so experienced he can turn around anything. Whether it’s your company or your Olympics, he knows how to walk in, figure out what’s wrong, and fix it.

Of course, the Romney campaign’s public posture is that nothing is going wrong. That’s natural enough. It is in the handbook that you don’t ever admit anything is running off the rails, even as you quietly get things back on track. The campaign got good news Thursday that helped them make the case that the situation was not as in need of change as the chattering class might think. The Gallup daily tracking poll shows that the race is tied. With 47 days left until Election Day, President Obama gets 47 percent and Mitt Romney gets 47 percent. Given Romney’s recent comments about the 47 percent, it’s clear that Gallup has a sense of humor. (We must remember to invite Gallup over for dinner some time—or at least cocktails.)

What better trait of a leader than not twitching at every sign of worry and discontent from supporters? Romney has had plenty of practice. He has had to go through the process of assuring his backers that there are no monsters under the bed several times. But time is drawing short, so changes are taking place. Romney’s aides say he will start to get more specific about what he will do if he’s elected. He’s named policies before, but that hasn’t done the trick. Now he’s going to try to explain how his policies can affect people in their daily lives.

That transaction requires the spark of connection, something Romney has not had so far. To help make that connection, the Romney campaign says the candidate is going to spend less time fundraising and more time directly asking for votes on the campaign trail. He’s put together a “bus tour” in Ohio, though it may just be a string of events held in proximity of a bus rather than a proper bus tour. In his television ads, he is going to start talking directly to the camera, in an effort to create some kind of bond.

This is where the recently revealed video of Romney speaking at a Boca Raton, Fla., fundraiser could be an impediment. To make his pitch, Romney can’t risk turning off voters. The fellow openly dismissing 47 percent of the country did not come across as very appealing. Because Romney lacks retail political skills, it’s hard for him to make connections that might be as indelible as on that secretly recorded video. As one Republican campaign veteran said, “I felt like when I was watching that video that it was the first time I’d ever seen the real Mitt Romney.” So Romney needs to appear genuine again—just not in a way that insults half the country.

To execute this new plan, Romney will need all the skills he says he would bring to the presidency. He needs to articulate the vision for the remaining 47 days, commit his team to it, and execute relentlessly. As he wrote in Turnaround: Crisis, Leadership, and the Olympic Games, “focus, focus, focus. Turnarounds that failed did so because management tried to do too many things rather than focus on what was critical.” His campaign has been conspicuously lacking in focus for weeks.

If Romney can make the connection, his campaign hopes to convince those voters disappointed in Obama that Romney has a plan for the future. As Romney aides describe it, those target voters don’t think that Obama is making things worse, but they are open to the pitch that Romney can make things better. They think Obama is just in low-performance mode, which isn’t good enough. To play on that feeling, the Romney campaign broke its global land-speed record for “gaffe” identification on Thursday. In an attempt to show that President Obama was resigned to being stuck with the middling status quo, they highlighted something he said at the Univision town hall meeting. “You can’t change Washington from the inside,” Obama said, when asked the biggest lesson he’d learned, “you can only change it from the outside.”

This is not a gaffe if the word is to have meaning at all. The idea that real change comes from the grass roots is what animated Obama’s campaign in 2008. It’s also what he’s been saying for months and months about his own campaign when he tells voters he needs them to help him change Washington. It’s the way an insider pretends that he is still the outsider. The idea that this suggests Obama has “given up” is further undermined by the fact that, in his next breath, the president says that it is this pressure from the outside that helped him pass health care reform and middle-class tax cuts. His point is about how you get around obstacles in Washington, not that he is resigned to them.

What Obama is doing here is trying to pitch his own turnaround. Washington is stuck. So he’s saying that in a second term, with even more help from the outside, he’ll be able to build on the successes of the first term where outside pressure helped win the day.

The president—like all of his predecessors—has an inflated view of his ability to bypass Congress by going directly to the people to get things done. It’s a lot harder for presidents to do this than they think, and it’s almost impossible if the country isn’t already with you. And, despite what Obama says, he didn’t have much success using the power of the grass roots to change minds on health care. He sure tried, attempting to activate his campaign team, Organizing for America, to build a groundswell. But he didn’t change any Republican minds in Washington. Indeed, public appetite for a change in health care winnowed over the time that Obama advocated for it. Last summer, in a famous showdown with Eric Cantor over the debt limit deal, the president said “don’t call my bluff” or I’ll take it to the American people. Cantor called his bluff, so Obama took it to the American people and largely failed. No pressure was created to move Republicans off their position, and the president soon enjoyed some of the lowest approval ratings of his presidency.

What the president said at the Univision town hall meeting was not only a harmless cliché about the importance of grass-roots power but a sentiment so weightless that it is a bipartisan bromide. Politicians of both parties repeat this phrase when they are trying to come up with something more clever to say or simply giving their brains a rest. For example, as Ben Smith pointed out, in a 2007 debate GOP candidate Mitt Romney said, “I don’t think you change Washington from the inside. I think you change it from the outside.”

Any self-respecting fan of the Tea Party would agree with the bedrock truth of this statement. It also echoes the challenge for the turnaround expert at this very moment. Facing pressure from the outside, Romney must show that he can make the change from within.