Toward the end of the 2011 movie Margin Call, a thinly fictionalized drama about the subprime mortgage apocaylypse, a senior trader at a large bank drives past some classy new homes, and it sets him off. He tells a young associate

People want to live like this in their cars and their big fucking houses that they can’t even pay for?” he rants. “Then you’re necessary. The only reason they all get to continue living like kings is because we’ve got our fingers on the scales in their favor. I take my hand off and the whole world gets really fucking fair really fucking quickly and nobody actually wants that.

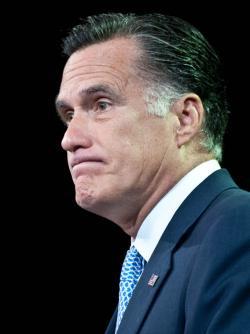

Replace one of the key words in there with “gosh-darn,” and I think you’ve got the tone conservatives want Mitt Romney to strike. Why, when Bain Capital comes up, does the candidate go into a crouch? When he miked up for a media tour to clean up the story last week, why didn’t he defend the private equity group he’d founded? The closest he came, in an interview with Jan Crawford, was “I’m happy that Bain went on, on its own, and did a number of terrific things.”

What kind of terrific things? The Obama campaign’s multi-pronged attack against Bain criticizes the company, and Romney, for profiting from outsourcing by investing in companies like Global-Tech Appliances, and for making money from the failure of companies like AmPad. Angry laid-off workers have been cinema verite’d and placed in ads. SEC documents have been discovered, used to Raise Questions.

Republicans are increasingly perplexed about this line of attack. This is how business works, they say to themselves. Who doesn’t know that? “We do know that the ability to export business around the world creates high-quality American jobs,” says Sen. Jim DeMint, who ran a market research firm before entering politics. “So, the idea that a company that has overseas subsidiaries is somehow hurting American jobs—the president counts that as outsourcing? The president doesn’t understand business.”

But the attacks are getting things done. Watching the Obama campaign force Romney to roll back the Bain claims he has made has been excruciating. Two months ago, the Romney campaign argued that their candidate deserved credit for “100,000 jobs,” because that was how many successful projects Bain had helped to fund. Obama allies quibbled with the math. When she launched the new Bain attacks, in a Web video responding to the Washington Post’s investigative Bain story, Obama-Biden deputy campaign manager Stephanie Cutter shamed Romney for vetoing “legislation that would have banned companies from shipping jobs overseas if they did business” with Massachusetts. “Now, that’s just good common sense,” said Cutter (even though her own incumbent candidate hasn’t implemented any legislation like that).

So how do the Democrats get away with it? Romney has preferred to concede the point than to defend some Bain Capital decisions that cost jobs. He’s done so ever since he started walking away from the company. In 2002, when he was he was running for governor, he told the Boston Globe he “had no involvement whatsoever” in decisions that happened during his leave of absence, like the Global-Tech Appliances deal .“The suggestion that somehow I’m heartless,” he said, “I’m this tough business guy who doesn’t care, could not be further from the truth.”

What was the implication of that statement? Did Romney actually disagree with any of Bain Capital’s decisions during his leave? Had he been there, would he have stormed into the boardroom and lit the contracts on fire? There’s nothing in his Bain Capital record to suggest it. He’s said, on other occasions, that it’s good to lay people off if they’re providing poor services. He’s pledged, if elected, to lay off 10 percent of federal workers.

Other GOP candidates have figured out how to talk about the difficult aspects of being a successful businessman. “Executive leaders have to make tough calls that won’t please everyone,” says Herman Cain, the one-time Romney rival (and 2008 Romney endorser) who made his reputation by strategically closing down some restaurants. “They can’t be afraid of criticism when they do so. I had to let people go at Godfather’s, too. It was necessary to turn the company around. Otherwise there would have been no company, and no jobs for anyone. Mitt Romney should point out that he helped build Bain Capital into a successful enterprise because he was willing to make tough but necessary decisions.”

In 2010, Wisconsin manufacturer and first-time contender Ron Johnson appeared to have screwed up mightily when he suggested that some job losses were products of “creative destruction,” Joseph Schumpeter’s widely accepted concept, and “if it weren’t for that, we’d still have buggy whip companies.” I vividly remember talking to labor activists who held sheafs of information about outsourcing-related layoffs, convinced that this would sink Johnson. But he beat Sen. Russ Feingold by five points.

But Johnson was a manufacturer. People like businessmen who build stuff. (Johnson’s best TV ad shot him against a whiteboard, sketching out how there were no people with his experience in the Senate.) As Matthew Yglesias explains, private equity isn’t so well-loved. People wince when a firm takes over a failing business and makes a profit while scrapping it.

But go back to “creative destruction” and to the angry trader from Margin Call. The people who make money this way—Mitt Romney, to pick a name at random—believe that they’re creating wealth. Some people get hurt. Other people—like Bain’s investors, the employees of Staples who keep their jobs in a revived company, and the customers who benefit from their products—are rewarded.

Romney shook up his campaign speech today, but he didn’t defend Bain Capital. He pivoted to attack the 2009 stimulus package for bad loan guarantees, and to ask for “government to get out of investing in individual businesses.” And he echoed the conservative media, which has portrayed remarks by Obama last week as proof that the president doesn’t think business owners actually build their own companies. He’s fighting one caricature of investment with another, which is probably easier than trying to explain the truth.