From time to time, from the end of 2008 through the start of his second presidential campaign, Mitt Romney would take out a legal pad and scribble his thoughts on the current foreign policy crises. The results might make it into a newspaper’s op-ed page, or National Review’s blog. Most of the ruminations made it into his book, No Apology, which he encouraged nosy voters to buy if they wanted to mind-meld with him.

“I spent almost nine months writing it,” Romney said at one of his first town halls in 2011. “A ghost writer … came back with the first chapter, I read it and said, ‘This’ll never do.’ And so I sat down and did the research and did it myself. So you’ve got me in there. The English isn’t that great, but the thoughts are in there.”

Not too many people bothered to check. Romney’s op-eds got maybe a fraction of the attention lavished on Sarah Palin’s Facebook wall posts. No Apology hit No. 1 on the New York Times best-seller list, but with two “daggers” indicating bulk orders—and Palin didn’t need that. The next time No Apology got written up, it was for tweaks to the paperback version that nudged Romney’s domestic policies closer to the Tea Party.

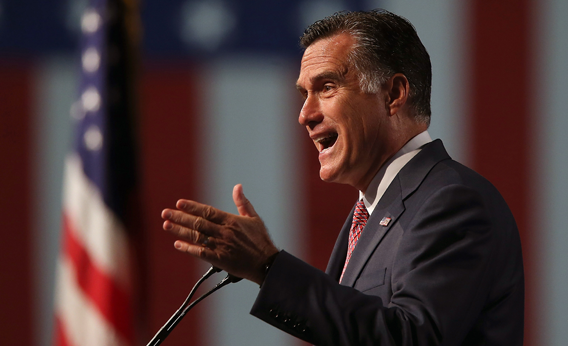

My point: Mitt Romney wrote thousands of words about foreign policy before he started farming this stuff out to surrogates. When he starts speaking in Europe and Israel this week, he’s going to build on a coherent, confident, and supremely aggressive philosophy of American supremacy. Rogue states are mere months away from acquiring nukes. The president is either defending America rhetorically or he’s hurting the cause of freedom.

The Romney criticism-campaign started in April, with a National Review blog post shaming Obama for not being angry about a speech delivered by Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega. “The words spoken by the leader of the free world can expand the frontiers of freedom or shrink them,” wrote Romney. “When Ronald Reagan called on Gorbachev to ‘tear down this wall,’ a surge of confidence rose that would ultimately breach the bounds of the evil empire.” Obama had reverse-engineered Reagan, and said that America sometimes “dictated” to other nations. “No, America has sacrificed to free other nations from dictators.” (Romney liked that line so much that he used it twice.) When Obama failed to talk tough, he told activists “in China, in Tibet, in Sudan, in Burma” that America lacked “resolve.”

If the Sudanese or Burmese resistance were truly disappointed in Obama’s speeches, they got over it. Burma held sham elections in 2010, then real elections two years later, which led to a National League for Democracy landslide and the reopening of U.S.-Burma diplomacy. South Sudan won independence in 2011, shortly after Tunisia, Egypt, and (eventually) Libya dispensed with its dictators. Giving Obama’s rhetoric the credit for that—well, that would be ridiculous. Romney was just arguing that the rhetoric would spook people into staying oppressed.

The “Obama should talk more like Reagan” critique appears again and again in Romney’s foreign policy oeuvre. It’s a theme, not a policy. Romney never accepts talk as a policy. “It is time to apply comprehensive, regime-crippling sanctions to North Korea,” he wrote in 2009, after a failed missile launch. “Assets should be seized; international financial capabilities terminated. North Korea should be recategorized as a state sponsor of terror.” If a nation acts out, if it makes moves towards nuclear armament, it needs to be isolated, immediately. “Si vis pacem, para bellum,” wrote Romney in 2011. “That is a Latin phrase, but the ayatollahs will have no trouble understanding its meaning from a Romney administration: If you want peace, prepare for war.”

America’s enemies are prepared. Barack Obama’s America isn’t prepared. In 2009, Romney surmised that Iran “may already have enough enriched uranium to build a bomb [a]nd it may well have secured access to missile technology from other nations.” In No Apology, written around the same time as that column, he worried that “the day is coming when [Venezuela President] Chavez announces a ‘peaceful’ nuclear program organized and supported by the mullahs in Iran.”

We’re three years on, and none of that has happened, but Romney was making a larger point. President Obama wasn’t starting from a position of strength. International institutions, even if they worked, couldn’t work as well as an idealized, America-led coalition. In No Apology, Romney mused about building a coalition like that, working around and outside the United Nations. “The history, achievements, and current commitments of NATO make it the preferred foundation for such a body,” he wrote. “Including other democracies like Japan, Australia, and South Korea could be accomplished by forming regional security councils and establishing a worldwide charter, but the NATO alliance should remain its foundation.”

That’s not a new Romney idea. National Review has been kicking the tires on a possible “Anglosphere” alliance since at least 2003. Whatever you think of the Daily Telegraph’s sneakily-sourced preview of the Romney trip, with an anonymous adviser riffing on Barack Obama’s un-Anglo-Saxon thinking, it captured Romney’s argument that a president should strengthen historic alliances until a historic rival is weakened. “When Poland and the Czech Republic are humiliated by us,” he wrote in No Apology, “they lose confidence in America’s support for them, and they may decide that they must incline more toward Russia.”

“May” is a much-repeated word in Romney’s foreign policy rhetoric. Conditionals—what could happen if America is weak—are played up, instead of our current selection of ugly slogs. In No Apology, he made no strategic recommendations for the ongoing war in Afghanistan. Instead, Afghanistan appeared as a test case of how a weaker nation could humble a stronger one—Afghanistan and the USSR, China and the United States. When Romney wrote op-eds opposing the new START Treaty, he worried that it would prohibit arms that “might not be part of the Obama administration’s current plans, but … could surely be part of a subsequent administration’s.”

And that’s the point. Romney wants to expand the size of the military. He admired, in No Apology, Ronald Reagan’s Cold War deficit defense-spending hikes, and he insists that Ronald Reagan’s bold speeches stiffened the spines of just the right people. “It is a mistake—and sometimes a tragic one—to think that firmness in American foreign policy can bring only tension or conflict,” Romney said this week, to the Veterans of Foreign Wars. “The surest path to danger is always weakness and indecision.”