Shortly before the 2000 election, Michael Obregon contacted the Miami-Dade Office of the Supervisor of Elections. Heads up: He had a new address in the city. Where should he go to cast his vote?

“I received a letter,” remembers Obregon, “one page, saying I wasn’t eligible to vote because I had a felony on my record.” He takes out the letter—he keeps it in a manila envelope labeled “Vote Problem”—and reads the warning: “The court system has notified the elections department that you are ineligible to vote. Pursuant to statute 98.093, we have removed your name from the voter registration record. You may contact the office of executive clemency.”

The problem: Obregon hadn’t committed a felony. Someone had apparently stolen the Bennigan’s bartender’s identity, opened some accounts, and gotten busted. That information churned into the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, which alerted the Florida Department of State, which passed the information on to the local supervisor’s office, which kicked the nonfelonious Obregon off the rolls.

“I had to send my fingerprints in,” says Obregon, “so I went to the police station, they took them, they sent them in. I got back a copy of my criminal record. It said, ‘There is no felony here.’ ” Thus began a mission to convince state bureaucrats in Tallahassee that he deserved the vote. It’s an ongoing mission. Twelve years later, Obregon still isn’t on the rolls.

As Obregon gives me more details and read from more paperwork, I grow progressively dumbfounded. Millions of people choose not to vote or forget come Election Day. But how do you let a state’s bureaucracy bounce you around for 12 years? Eventually, even if the various state agencies change their numbers or blow you off, don’t you try to go above them?

“I could probably try harder,” says Obregon, “but I just get discouraged.”

Here’s the paradox of the new voter ID crackdown, of the 38 states that have debated or passed legislation that puts more demands on voters. The new laws—and in Florida, new executive campaigns—ask voters to show driver’s licenses at the polls, or prove their eligibility with birth certificates, or prove that they’ve never had a felony, or prove that they are citizens of the United States.

Doing that involves navigating your state’s bureaucracies. Those bureaucracies have been shrunk or frozen by years of belt-tightening. They rely on data from other cost-cutting organs of the state. Imagine giving some endomorphic amateur athlete a low-calorie diet and limited access to a gym. He’s training for a mile-long fun run, so there’s no pressure. All of a sudden, you panic about the threat of Sprinting Fraud or something, and you inform the runner of his new task: Run a timed 3.5-mile circuit, tomorrow.

Florida, stereotypically enough, demonstrates some of the problems. Obregon was caught up in a notorious purge of felons based on a list so flawed that perhaps 20,000 people were disenfranchised by accident. Legislators, disturbed by fraud in a 1997 Miami mayoral race, hired the now-defunct Database Technologies to compile its list. Atlanta-based ChoicePoint bought DBT before the 2000 election, so it fell to them to explain—in front of courts and special civil rights committees—how it got screwed up so badly.

“Once DBT created a list of potential felons, using loose standards, it was handed to election commissioners,” explains former ChoicePoint spokesman James Lee. “That was where the system broke down. Some commissioners did the work. Some set them aside. Some took the lists at face value and said, ‘Well, they developed this, and they’re experts, so they must be right.’ ”

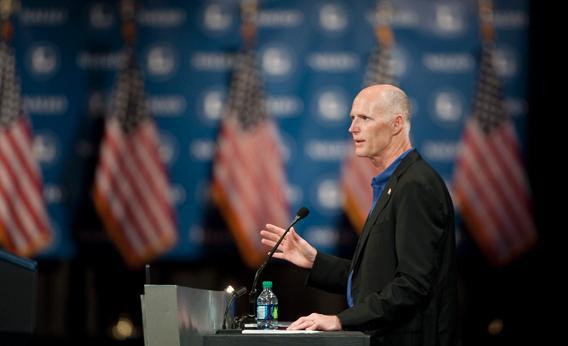

Florida, compelled by the Help America Vote Act, spent the next decade trying to avoid another DBT-style bungle. And then came Gov. Rick Scott. He’d once been listed (mistakenly) as dead, shrugged, and cast a provisional ballot, assured that his vote would count. (HAVA created provisional ballots for people who show up at the polls, aren’t on the registration list, and can prove that the state got it wrong. Floridians cast 35,365 of them in the 2008 election, and slightly more than half got counted.) Early in his term, Scott asked his secretary of state, Kurt Browning, how they could make sure noncitizens didn’t cast votes.

Browning put the state elections division to work on compiling a loose list of noncitizens, using the databases available to them—transportation, law enforcement, and so forth. When he left office in January, the state was still whittling down a list of 25,000 bogus voters, which he knew included false positives. And then, according to Miami Herald reporter Marc Caputo, Browning’s replacement got spooked by a local news report on felon voters. In April, the state sent out a pared-down list of 2,700 potential noncitizens. After that, a circus: World War II veterans holding press conferences to explain how they were cheated and three federal lawsuits that have ended, for now, in what Pasco County Elections Supervisor Brian Corley calls “limbo.”

“We sent out certified letters to the 13 people on our list,” he remembers. “They said, basically: Hey, the state of Florida thinks you may not be citizen. Of the 13 people, we only reached four. Two of them were not happy and faxed us their birth certificates. Two of them weren’t citizens. Which leaves nine people in limbo.”

If anyone has figured out how to navigate the noncitizen voter problem, he has not revealed the trick. James O’Keefe, the conservative investigative journalist, has dispatched his Project Veritas reporters to multiple swing states (and D.C.) to prove that anyone can steal a voter’s identity if the state doesn’t ask for ID. In North Carolina, O’Keefe used jury pool lists to find noncitizens and show how they could sneak into the polls. But the lists were flawed, and two of the supposed noncitizens in the video turned out to be naturalized, eligible voters.

“Citizens can indicate they are a noncitizen on those forms to get out of jury service,” explains O’Keefe. “You pull the records of all registered voters and cross-tabulate the lists. Many of the people who claim they are noncitizens perjure themselves—as was the case with one of the individuals in our film.” And the records are incomplete. “Some counties destroy the original jury refusals, leaving you only with data you can’t verify.”

It’s difficult to prove that noncitizens are on the rolls, and it’s not like there’s proof that these voters are skewing elections. “I don’t think there’s a huge running to the polls of noncitizens,” says Corley. “The last thing you want to do in that situation is draw attention to yourself.” But if you want a new law that the government is seriously ill-equipped to enforce, look to Mississippi. In order to get a free voter ID card there, you need to supply a birth certificate. Some women, with new married names, are unable to use birth certificates to prove their identity. If they lack copies of their birth certificates, they need to apply for them with—of course—some kind of ID card.

And here’s the irony. Michael Obregon, who can’t vote, has a passport. He got his first one “as a kid.” He renewed it “a couple of years ago.” Getting a passport means showing the State Department proof of identity and sending them $165. The passport system wasn’t concocted in a hurry due to a legislative-media panic. It doesn’t require multiple state agencies to work in concert, quickly and seamlessly. And so you get attrition, you get paranoia, and you don’t get any closer to a voter-checking system that works.

“I don’t know if I trust the whole system, you know?” says Obregon. “I mean, how hard did they check to see if my civil rights were being taken away?”