The embeds found the hotel before anybody else did. The ballroom where Newt Gingrich would suspend his presidential campaign was tiny, and there were only four comfortable tables for the press, so the embeds snagged them first. Only fair. These TV reporters, none of them older than 25, had been collecting video of Gingrich until long after their networks stopped using it. They did not earn the approval of Winston Cornwall, a strategist who said he’d done some work with Gingrich in the 1990s, who stalked the hotel hallway in a blue blazer.

“The teenagers are here,” said Cornwall. “I’m disappointed. I guess I was expected some kind of rally with Newt’s supporters and staff. But it looks like a press conference. I don’t even see any top reporters.” He craned his neck toward the hotel elevators. “I stand corrected. There’s press royalty right here!” He’d spotted the Washington Post’s Dana Milbank, who writes a daily “Washington Sketch” and materializes at events that carry a Defcon 1 risk of farce.

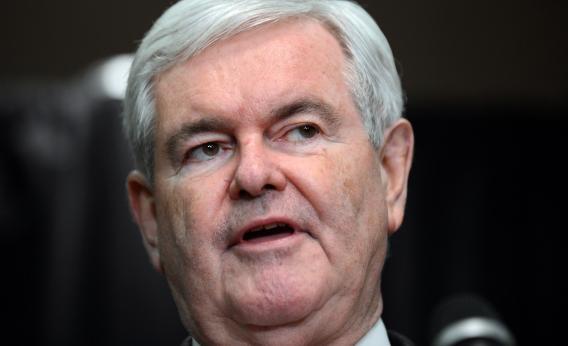

Newt Gingrich, who has been written off as a has-been at least twice, had never really given a speech like this. In 1998, when he gave up the speaker’s gavel, the announcement came via a statement read to reporters by a spokeswoman. Gingrich himself was sequestered in Georgia, brooding. In the summer of 2011, when the political press ran early obits of his presidential campaign, Gingrich fed off it, kept on running, and won two primaries. His Hilton Arlington address would be his first-ever career valedictory.

People like to be in the room for things like that. As 3 p.m. approached, Gingrich’s brother, daughters, and extended family found the ballroom and chatted with each other.

“What have I been up to? I’ve been letting out my skirts,” said a staffer talking to Gingrich’s brother Randy. (Randy looks like the speaker might look if he was a head taller and got picked first in gym class.) “I want to tell Newt, I put on 20 pounds for you.”

R.C. Hammond, Gingrich’s perpetually arch spokesman, alternated between chats with supporters and quick Q-and-As with reporters. The Romney campaign, he said, had been generous giving Gingrich access to helpful donors. Gingrich would campaign wherever he was wanted. The campaign picked this hotel because “the staffer who picked it went in a concentric circle around our office, looking for whatever room was closest.”

Nathan Naidu, Gingrich’s less arch spokesman, found the people who’d spent the most time on his campaign bus. At one point, all of them had written stories about what a disaster Newt 2012 had morphed into. Bygones. Naidu pointed at the unfamiliar press—which included, for some reason, two Japanese TV stations—that had occupied all the free space in the room. “I don’t remember them from the bus!” he said. “I don’t want to see anyone who wasn’t on the bus.” He excused himself when he spotted a photographer who’d covered Gingrich: “I need to go hug somebody I like.”

Many photographers had to go without hugs. Two of them debated among themselves about whether they’d paid enough to park—was two hours enough? Would Gingrich go longer than that? A few Gingrich staffers and volunteers snuck into the cramped press rows and reminisced about the campaign. Louis Altobelli had joined the campaign in March, long after it was clear that Gingrich couldn’t win. His job: Calling delegates. It was incredibly unrewarding work.

“I talked to delegates that Newt won in Tennessee, who said they weren’t going to back him anymore,” said Altobelli. “It was the machine. That’s the word right now. We were outspent, and it’s too bad, because it would have been nice to have somebody different, instead of the machine’s choice.”

At 3:10, Gingrich’s daughters, two of their children, and one of their husbands took the stage. They stood stoically for a while. Finally, Callista Gingrich emerged from behind the stage, trailed by Newt. He took in the scene, flashed a “gee, can you believe it” glance at his wife, and thanked his daughters for bringing the kids.

“They brought, I think, the two best debate coaches,” said Gingrich. He welled up. “Whatever I did well in the debates, I ascribe it to Maggie and Robert.”

That was all the emotion we’d get. For the last time, Gingrich described all of the facts he’d learned, or he’d taught people, in a year’s worth of campaign stops. New Hampshire, he argued “is a model of balancing the budget the right way. In New Hampshire, they start with the revenue number and they appropriate up to the revenue number.” Herman Cain’s endorsement was “tremendous.” The people of South Carolina, too, were “tremendous,” and “the size of the victory was historic.” But he’d let them down, and would return to the state sheepish about “breaking their perfect record” of picking the eventual Republican nominee.

Gingrich was almost honest about his campaign. Newt 2012 didn’t work out. It stayed competitive only because of “Sheldon and Maria Adelson who single-handedly came very close to matching Romney’s Super PAC.” But when it sounded like he was about to blame himself for a mistake, he’d find a way to reroute and blame the media. “One of the topics I feel saddest about not talking about very well is brain science,” he said. And why? Because he struggled to take the concept “from the world of science, where everybody agrees about it, to the world of politics, where nobody understands what it means.” He had erred, probably, in talking about a moon colony that could achieve early statehood. But, reporters: “You may have noticed, the founders of Google are talking about mining an asteroid.” Smart people, as ever, knew that he was right. “I am cheerfully going to take back up the issue of space.”

The difference between Gingrich’s campaign and the average presidential effort was honesty. Nobody runs for president thinking he or she is mediocre, and that he might only solve 20-30 percent of the nation’s crises. Candidates have enormous egos. Gingrich just led with his. The loving staffers and family around him were probably less aware than him of what the campaign might cost him. His empire of influence and literature was a little diminished by the campaign. Solution: Remind his audience that the empire was going to rise again. “I’m grateful to Human Events,” said Gingrich, “for publishing my newsletter. My newsletter from today focuses specifically on religious liberty.”

As he described this, a reporter in the front row fiddled with Instagram. The only news Gingrich had left in him was about Mitt Romney. Would he endorse the man that every other loser has endorsed? “I’m asked sometimes,” said Gingrich, “Is Mitt Romney a conservative? This is not a choice between Mitt Romney and Ronald Reagan. It’s between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama.”

That was as far as he’d go. After he wrapped, his fans and family went back to their hallway catch-up talks. Reporters located Hammond and asked whether or not Gingrich had actually ended his campaign and endorsed Romney.

“The week after the election,” joked Hammond, “we’ll be in New Hampshire. We’ll be in Iowa by Thanksgiving. It’s good to see you guys!”

The press wouldn’t let Hammond go. Was this an endorsement? No. “Stay tuned” for one. When would it happen? “Leave me alone!”

Hammond disappeared. The reporters agreed: That was a perfect way to end this.

Watch a Requiem for Newt:

.