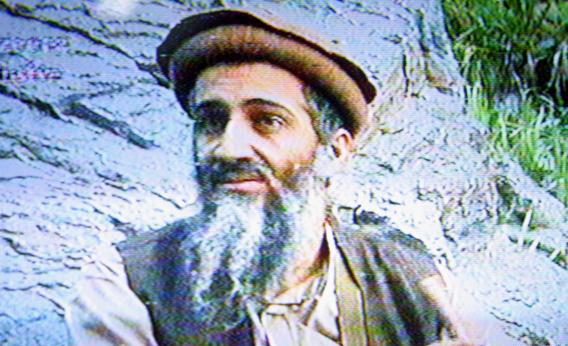

Osama Bin Laden killed people. He taught others to kill. He built a global network of mass murder. He gave his life to death.

But that wasn’t his goal. We know what he really wanted, thanks to documents seized from his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, by the Navy SEALs who terminated him. The documents, released yesterday by the U.S. government, show Bin Laden saying in private what he said in public: He wanted to serve Islam and honor God’s commandments. He was obsessed with right and wrong. He condemned the Times Square bomber for betraying an oath of loyalty to the United States. Bin Laden and his lieutenants even fretted about whether it was OK to invest in stocks.

Bin Laden wanted to do the right thing. And he wanted to win hearts and minds. He wanted to persuade people, not kill them. He thought killing was the way to get there.

That’s what makes the Abbottabad documents so poignant. They show the world’s most feared terrorist, at the end of his life, grappling with the moral and political failure of terrorism.

Among the collection, the fullest picture of Bin Laden’s thinking emerges in a 44-page letter he wrote in 2010. He chastised followers who had reinterpreted tatarrus—an Islamic doctrine meant to excuse the unintended killing of non-combatants in unusual circumstances—to justify routine massacres of Muslim civilians. This descent into indiscriminate slaughter, he warned, had turned Muslims against the jihadi movement. Bin Laden wrote that the tatarrus doctrine “needs to be revisited based on the modern-day context and clear boundaries established.” He asked a subordinate to draw up a jihadist code of conduct that would constrain military operations in order to avoid civilian casualties.

Of the groups affiliated with al-Qaida, Bin Laden found particular fault with Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. He condemned a TTP attack on members of a hostile tribe, declaring that “the operation is not justified, as there were casualties of noncombatants.” Bin Laden’s subordinates wrote to the TTP’s leader, warning that its “methods and behavior” violated Islamic law and risked “corruption of the jihadi movement.” The Abbottabad documents show similar revulsion at the tactics of al-Qaida’s Iraq affiliate, which ruthlessly blew up Shiite civilians. One adviser called on al-Qaida to repudiate such “ignorant/ungodly criminality.”

It wasn’t just the killing that worried Bin Laden and his lieutenants. It was the oppressive fanaticism. In Somalia, Bin Laden cautioned against al-Shabab’s harsh and rigid interpretations of Islamic law. He counseled the group to grant “the benefit of doubt when it comes to dealing with crimes and applying Sharia,” so that the most extreme punishments could be avoided.

One Bin Laden associate worried that Iraqi jihadists were alienating the public by talking like “extremists.” Another criticized online jihadi forums as “biased” and “repulsive to most Muslims” because of the commenters’ “bigotry” against versions of Islam other than their own. A third urged his comrades “to rid ourselves of the accusation of inflexibility and narrow-mindedness” and “broaden the horizons of our brethren.” He pleaded: “We must avoid the stigma of being a one-dimensional sect, opposed to all others. We are Muslims following the teachings of Islam and we are not the owners of the Salafist way, and must avoid [stereotyping] each other.”

These appeals for tolerance, like Bin Laden’s appeals to avoid targeting civilians, were generally reserved for Muslims. But some advisers went further. One excoriated al-Qaida’s Iraq affiliate for attacking churches and antagonizing Christian Arabs who might otherwise support the anti-American insurgency.

In Yemen, Bin Laden urged his allies to seek a “truce” that would bring the country “stability” or would at least “show the people that we are careful in keeping … the Muslims safe on the basis of peace.” In Somalia, he called attention to the extreme poverty caused by constant warfare, and he advised al-Shabab to pursue economic development. He instructed his followers around the world to focus on education and persuasion rather than “entering into confrontations” with Islamic political parties.

How could a man responsible for so much killing write these things? How could a man who wrote such things be responsible for so much killing?

The answer that emerges from the Abbottabad documents is that Bin Laden didn’t understand what he had unleashed. Only at the end did he begin to face the consequences of terrorism, not for all the infidels he had slain, but for Islam, justice, and al-Qaida. His movement was destroying itself.

That, inevitably, is what terrorism does. Most people think it’s gravely wrong to kill children and other noncombatants. They don’t like sectarian conflict or perpetual war. They don’t want to live under oppressive government. If you go around blowing up crowded markets and chopping people’s hands off for petty crimes, they’ll turn on you.

Bin Laden blamed these moral and political mistakes on his followers. He thought they had misunderstood and abused the ideas he preached. He never recognized that the cancer was in the ideas themselves. He thought you could blow up markets full of Christians without blowing up markets full of Muslims. But once you start blowing up markets—and rationalizing it through creative interpretations of scripture—it’s easy to justify killing whoever’s in the way, or whoever’s available. And once you declare war on infidels, it’s easy to extend your definition of infidels from non-Muslims to Shiites.

Bin Laden was too deep in this madness to find his way out. But his letters are a warning to those who would follow. If you kill civilians in God’s name, you’re on the path to betraying God, your values, and your people. You’ll destroy yourself and your movement. Turn away.

William Saletan’s latest short takes on the news, via Twitter: