Expecting presidential candidates to be candid with voters is such a quaint idea you’d expect to find it on Pinterest. There it is, next to the adorable confectionery and wedding dog photos. Well, I like quaint, and if you also like a Dr. Seuss saying stenciled on an ambiguous decorative item, then join me on my search for candor in the 2012 presidential campaign. I need your help.

We need honesty now more than ever. There are big decisions to be made. A $1 trillion deficit requires a retooling of much of the federal government and a reworking of the tax code. At the very least, Americans are going to have to accept big changes in what they’ve come to expect from their government. Or they may have to face brutal reductions in public services they count on like the military or quality medical care for the elderly.

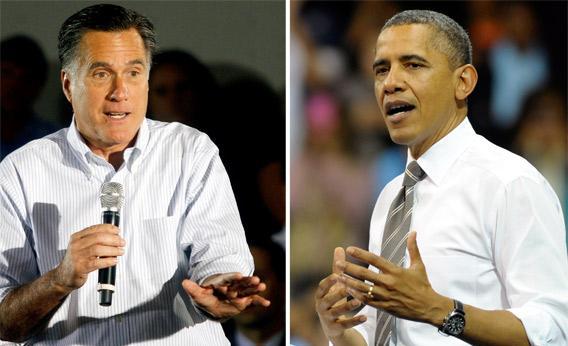

Mitt Romney attacks President President Obama for not being candid, saying his hot mic moment with the Russian president “calls his candor into serious question.” The Obama team makes the same charge about nearly every word that comes out of Romney’s mouth. In the books each candidate has written, they’ve both said that a lack of honesty is what’s ruining politics.

Successful politicians must shade the truth, embellish it, and keep everyone happy by avoiding it. But if this year’s contenders are going to go on so much about candor, it’s worth asking how honest has either candidate actually been. At a later date we’ll try to figure out who tells hard truths more often. First, though, we’ll need a baseline: What is the most candid thing each candidate has said? I asked each campaign to furnish an example. By candid, I don’t mean specific. I mean, what’s the best example of a candidate saying something honest enough to cause voters a moment of discomfort.

Mitt Romney:

“Our next president is going to face difficult choices. Among these will be the future of Social Security and Medicare. In their current form, these programs will go bankrupt. I know that, you know that, and even our friends in the other party know that. The difference is that I will be honest about strengthening and preserving them, and they won’t.”

Being candid about how you’re going to be candid is no kind of candor at all. Taking credit for honesty you’re not actually offering while criticizing the other party for not being honest compounds the offense, creating a net reduction in candor. Romney could say that under the plan he favors, Medicare recipients who expect a defined benefit will have to switch to a plan in which the contribution is defined. That would get a conversation going.

Romney has been specific about the tax rate reductions people will get, but when it comes to being specific about how those reductions will be paid for, he’s less so. The Wall Street Journal reports his economic advisers are having trouble getting the numbers to add up in a way that isn’t politically unpopular.

Of course, Romney had his own hot-mic moment a couple weeks back when he appeared to be speaking candidly with wealthy campaign donors. Some journalists overheard Romney offering a Dixie cup of detail about closing loopholes for mortgage interest deduction for second homes and trimming some federal departments. But apparently if we thought we heard some candid ideas from the Republican challenger, we were mistaken. Romney’s campaign quickly rushed forward to say he was just repeating ideas he had heard on the campaign trail.

President Obama:

“So this notion that somehow we’re offering smoke and mirrors—try to tell that to the Democrats out there, because part of what we’ve done is we’ve been willing to cut programs that we care deeply about, that are really important, but we recognize that given the fiscal situation that we’re in, everybody has got to make some sacrifices; everybody has got to take a haircut.”

The Obama campaign offered several other examples that were very much like the one the Romney camp offered: quotes about how hard choices had to be made without being specific about what those choices would be. This quote, while offering no actual candor, does point to cuts in specific programs like home heating aid, community block grants, and education programs that are in the neighborhood of the type of hard truths we were looking for. They are bad news for voters that the president would like to keep happy.

The president has an advantage over Mitt Romney in this way. Because his actions have consequences—candidates, by contrast, can pretty much say any old thing—his aides can point to support for legislation like Dodd-Frank where the president’s advocacy damaged him with the banking industry. Several Democratic fundraisers have said this has led to the slow pace of fundraising on Wall Street.

The president could be very specific if he wanted to be. During the budget negotiations that collapsed surrounding the grand bargain, he considered some cuts to entitlement programs that he never talked about publicly. We’re not likely to find out what those trade-offs are now that we’re in an election season.

There is a known bug in this experiment. Campaign aides are not the best ones to ask about their candidate’s candor. The modern campaign is a series of emergency exercises where aides are trained to smother any compromising thought that makes a break for it. Romney has (rather candidly) talked about his specific strategy against specificity—the more detailed you are the more you’ll be attacked.

I can, however, think of a moment when Mitt Romney told farmers and businessmen at a meeting in Treynor, Iowa, he wasn’t going to support their ethanol program. “I’m not running for office based on making promises of handing out money,” he said. “Let Detroit Go Bankrupt,” was a pretty gutsy thing to say, too. (Although the campaign says that wasn’t the governor’s actual wording for the headline of the op-ed he wrote arguing against the auto bailout, it does approximate the sentiment of the piece.) Romney is paying more of a price for those words in the Midwest than Obama did in 2008 for his comments about fuel efficiency standards.

The lack of honesty in campaigning is nothing new. In 1920, H.L. Mencken observed that “the first and last aim of the politician is to get votes, and the safest of all ways to get votes is …to be happily free from any heretical treason to the body of accepted platitudes—to be filled to the brim with the flabby, banal, childish notions that challenge no prejudice and lay no burden of examination upon the mind.”*

Still, we must hope. Sure, candidates shouldn’t be asked to commit political suicide, but they must be brave enough to say something more bracing than a cloth diaper. So I will continue to look for examples of candor during the campaign season and try to break off pieces of it from the permafrost of the two campaigns. If you have a better example, please email me at slatepolitics@gmail.com, and I’ll elevate it to the top of the running list. This isn’t necessarily an exercise in comparative candor. I’m just looking for the truest thing said by each candidate. Perhaps by the end of the campaign we might find an example of something Obama or Romney has said that’s provocative enough that we’d really want to tack it up on the wall, and say, “Hey, thanks for being honest.”

Correction, April 25, 2012: This article originally misspelled H.L. Mencken’s name. (Return to the corrected sentence.)