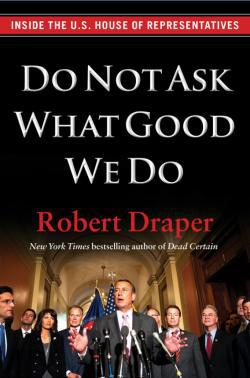

I was halfway through Do Not Ask What Good We Do when I felt moved to email Robert Draper. Another title for his book, a history of our current House of Representatives, might be Worst Congress Ever.

Draper wrote back. “That’s about 50 times pithier than Do Not Ask What Good We Do.”

To research the book, Draper embedded with new and senior House members—mostly Republicans—shortly after the 2010 election. His reporting took him from the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords through the spring 2011 passage of the government-funding continuing resolution through the soul-deadening summer of the debt-limit vote. It took about as much time as an average pregnancy for 87 new legislators to become convinced that Congress didn’t actually work for them.

The intended punch line: For the new guys, this is how Congress always looks. The rest of Draper’s title quote, uttered by a retiring House member in 1796, is asking what good the body can do “is not a fair question, in these days of faction.” Well, phew—if the legislative branch was born dysfunctional, and we’ve made it this far, America might survive the Tea Party Congress.

I said might. Here’s a quick guide to the more embarrassing or telling moments from Draper’s insta-history.

The Democrats: Anthony Weiner Division

The first juicy Draper leaks appeared in Politico and the New York Post last week. News Corp.—the bane of Anthony Weiner’s existence—got to display his corpse and take a few more stabs at it. How much more can you reveal about a man whose erect (clothed) genitals are only a Google click away? You can reveal how much his former colleagues despised him. Weiner comes off as a buffoon with zero strategic skill and 100 percent confidence in said skill.

On MSNBC one day, when his party still controlled Congress, he claimed that a health care bill minus a public option would lose 100 votes. “That number had just popped into his head,” reports Draper. “He’d uttered it without any reason to believe it was accurate. And yet it soon became a widely quoted number.” In 2011, as his profile rose, he gave his leaders advice such as “get a hundred and fifty of us and agree not to raise the debt ceiling—that’s the Republican majority’s job.” They did not listen. Before the State of the Union, he told friendly reporters that he’d “sit next to two Republicans tonight—one I like, and one I can say ‘fuck you’ to. Just for ballast.’”

The Democrats: Non-Weiner Division

Draper finds the House Democrats in a jumpy, irritated, despondent mood. They were warned by pollster Stanley Greenberg, at their first Obama-era retreat, that many of them would fall in 2010. They panicked anyway. Former members like John Tanner (Tennessee) and Glenn Nye (Virginia) wail to Draper about how Nancy Pelosi ruined them by forcing tough votes, watching them lose, then running for leader again. “Instead of running a race where it’s me against the other guy,” gripes Nye to Pelosi, “I’ll be dealing with the same ads.” Nye, defeated, gives up and joins the private sector.

The remaining Democrats find unity only when Paul Ryan introduces his budget and they know what they’re against. Rep. John Dingell is amused to learn the sexual definition of the term teabagging. “That’s disgusting,” he tells his tutor, “but it’s funny, and I’m going to keep using it.” Democrats find another kind of unity in the debt fight, as the president betrays them. “The president is the worst negotiator who has ever owned that title!” says California Rep. Dennis Cardoza to Pelosi. “I didn’t know Millard Fillmore, but… he’s the worst. He doesn’t know how to do this.”

Pelosi’s response: “Yeah, but he doesn’t think so.”

Draper’s Republicans sing the same notes. Rep. Raul Labrador, a freshman from Idaho, speaks up in a meeting with Obama, assuring him that the GOP can work with him.* “The new House liaison for the White House,” writes Draper, “stepped forward and handed Labrador his card.” This is the universal sign of “whatever.” Obama never calls Labrador. But the people who actually reach out don’t do any better. When a clutch of House Republicans walked into the Senate to personally lobby Democrats for “ayes” on the old Cut, Cap, Balance bill, Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia says, “If you could find three other votes, I’d go along.” They don’t find them; he doesn’t go along.

Allen West: Asterisk With a Bayonet

Other people seem to figure out Allen West’s celebrity before he does. Draper goes back to the Article 32 hearing that West faced after interrogating an Iraqi prisoner with a loaded gun and firing it an inch away from his head.* His attorney, Neal Puckett, is “awed” by West’s performance in the hearing. “The nation’s going to see you as a leader who stands up for what’s right,” says Puckett. “Allen, you should run for Congress.” West demurs and says he just wants to avoid jail. But Puckett proves to be right. West, a Florida Republican, wins his seat and informs his new staff of his old standing orders. Keep your bayonet sharp. Keep your individual weapon clean. Be the expert in your lane, and knowledgeable in another. Be professional.

West is blunt. When Barney Frank mocks the Republicans for a marathon series of amendment votes, West calls him “a guy who for all practical purposes should be in a pink jumpsuit for what he did.” The Congressional Black Caucus issues a condemnation of the Ryan budget. West disagrees. CBC Chairman Emanuel Cleaver soothes him by promising that “we’ll make sure that on positions that we send out, we’ll have some kind of asterisk that suggests that this is not reflective of all the members of the caucus.”

The Debt Ceiling: Everybody Loses

Republican leaders figured out early that some members of the freshman class simply didn’t get macroeconomics. Majority Leader Eric Cantor warned Democrats about it when the debt fight began. The “cardinals” on the appropriations committee have zero regard for Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy. “He didn’t seem to know the difference between ‘obligations’ (funds allocated) and ‘outlays’ (funds spent),” writes Draper. “[A]s a result, he was in no position to educate the freshmen.” McCarthy compounds the problem with field trips where freshmen members watch debt auctions and are “rendered speechless, as if bearing witness to a state-sponsored execution.” When White House veteran Jay Powell gives Republicans a Power Point, explaining the need to raise the limit, Rep. Phil Gingrey of Georgia blows him off. “You did a nice job with your presentation. But we heard from Karl Rove yesterday—and frankly, I like him better.”

The Show-Horses: Universally Despised

There’s a bipartisan overlap between the Republicans who make liberals angry and the Republicans that their colleagues don’t respect. Rep. Joe Walsh “had told some of his Republican colleagues, with a straight face, that he had a ‘cult following.’” So a staffer shows Rep. Renee Ellmers—a star that the leaders actually like —a tape of Walsh getting flayed by Chris Matthews. “See,” says the staffer, “this is exactly why (a) we don’t do Hardball, (b), we vet all the requests we get, and (c) we’re prepared.”

South Carolina’s four freshman Republicans, all of them deeply conservative, form a bloc that votes against any spending bill. When he’s whipping the continuing resolution, Rep. Peter Roskam asks if they “intend to blindly follow Jim DeMint.” When they refuse to back the strict debt deal that narrowly passed the House—the doomed one, right before the actual deal—McCarthy blows up at them. “Screw it! No deal! We’re done!” And yet when the four freshmen need to save funding for the Port of Charleston, they swallow pride and get a favor from a Democrat, Rep. James Clyburn. “The money was procured,” reports Draper. “It was not an earmark. Rather, the telephone request was direct and paperless, a so-called phone mark.”

Do not leave an email trail of what good they do.

Corrections, April 25, 2012: This article originally stated that Rep. Raul Labrador is from Utah. (Return to corrected sentence.) This article originally referred to West facing an Article 23 hearing. It was an Article 32 hearing. (Return to the corrected sentence.)