Illinois primary day was a laundry day for Mitt Romney. He washed his shirt in the sink and then took Rick Santorum to the cleaners. The former Massachusetts governor beat his closest rival handily, 47 percent to 35 percent. It was the first no-caveat, everyone-is-watching, takes-place-in-a-location-you’ve-heard of contest that Romney has dominated since his victory in Florida two months ago.

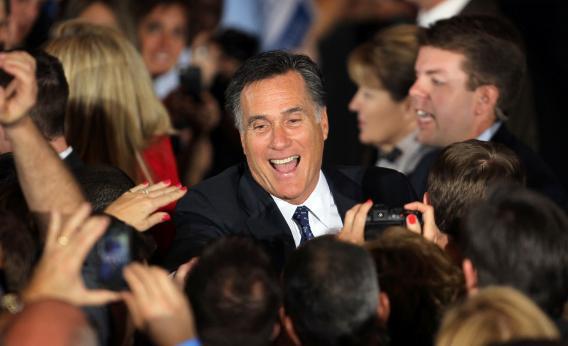

The Republican nominating contest could take a long time. So it’s probably wise not to clutch the dashboard every time there’s a bend in the road. Still, there was something different about Romney’s win in Illinois. On recent primary days, he has been able to claim he won the most delegates, but Santorum has emerged from those nights with the energy and excitement. Tonight Romney can crow about having the excitement and winning the most delegates in a state where he didn’t have a home field advantage like Michigan or a regional connection like New Hampshire. Even when he has won, Romney has had to say unsatisfying things like “a win is a win.” After Illinois, he can just smile. Everyone gets it.

The Republican race will continue, but the conversation may change. Can Romney turn the victory into the last piece of data necessary to get the party to finally rally around him as the eventual nominee? Romney will argue that he is “bringing the party together,” a claim that rests on whether enough people believe that he is acceptable to conservatives. He got some evidence in Illinois to help him make his case. Romney won his usual constituencies—moderates, the wealthy, and the well-educated. But he also improved his performance among the 64 percent who identify themselves as “conservatives.” Romney won 47 percent of that group to Santorum’s 39 percent. He also won 47 percent of the vote from those who support the Tea Party to Santorum’s 36 percent.

Romney improved his standing in other areas, too. When voters were asked who best understands the concerns of regular Americans, he won that group with 36 percent. He dominated in the areas he does best in, scoring high among voters who are most concerned about beating Barack Obama and who say the economy is their primary concern.

Will it be enough? Perhaps the win was decisive enough to get Republicans to fall in line, but the exit polls showed that Romney still has work to do. Forty-four percent of those who voted for him said they still had doubts. There are no party elders to finally call everyone in to dinner from their rumble in the back yard. But if Jeb Bush, Mitch Daniels, or Haley Barbour put their arm around Romney, it would generate some coverage in conservative circles and perhaps that would translate to even more lopsided wins in future states.

The pressure is on the also-rans. At some point, argues one Romney adviser, Santorum and Gingrich have to worry about their future viability as Republicans. They don’t want to become branded as spoilers. But the Republican Party has cracks in it and a loud minority wants leaders who never surrender, thumb their nose at the establishment, and battle for principle. If you want to be the favorite after-dinner speaker for that crowd, there’s no reason not to take the fight to Tampa.

Unless, of course, you start to look ridiculous. Newt Gingrich’s theory is that he’ll pull out a victory in a big convention fight in Tampa. But he has to actually win a contest in some place other than South Carolina and Georgia. Instead, he has launched a quixotic tour that includes zoos and fine-dining establishments, arguing that once he gets to Tampa he’ll be able to convince delegates to pick him. He’s a flawed candidate. That’s why he’s not winning. His flaws aren’t going to suddenly evaporate, no matter how good a show he puts on for delegates. Gingrich has such a devastating and derisive wit it’s a shame that we can’t hear Gingrich on Gingrich’s strategy.

If Romney was able to expand his pool of voters in Illinois, Santorum was not. He won among those who consider themselves “very conservative” and those who “strongly support” the Tea Party. He owns the far-right wing of the party but showed no ability to grow out from that base. That may be due to the fact that Romney once again buried Santorum under a mountain of negative ads. Team Romney outspent Santorum 18-1. At $3 million in combined spending between Romney and his Super PAC, that’s $7.50 for every Romney vote.

Santorum won among the 43 percent who identified themselves as evangelicals, with 46 percent to Romney’s 39 percent. Still, that was one of Romney’s best performances with that group. We also learned something else about Santorum’s support among religious voters. For the first time, the exit polls asked people how often they attend church. Santorum won among those who attend services more than once a week, but Romney won all other categories—those who attend weekly, a few times a month, a few times a year, and never. Santorum’s base isn’t so much religious as devoted to their faith. That was also true of Catholics. Santorum wins among those who attend mass more than once a week. Romney wins the cafeteria Catholics and all the rest. Again, Santorum has locked up the most intense part of the party but nothing else.

The exit polls also gave some insight into whether Gingrich’s departure would help or hurt the remaining candidates. It’s a complicated question that relies on Gingrich being more than a candidate in name only, which was pretty much his role in Illinois, where he finished fourth. In the limited future states where he might be a factor, like Texas, North Carolina, or Arkansas, a strong showing could draw some at-large delegates from Romney, slightly slowing his march to 1,144 delegates. On the other hand, if he performs well in those states, he could take votes from Santorum and rob him of delegates and a win. The latter scenario rests on the theory that Gingrich takes a larger share of voters from Santorum. That was only slightly true in Illinois. When voters were asked who they would favor in a Santorum and Romney matchup, Gingrich voters made up 10 percent of Santorum’s share and 8 percent of Romney’s share.

The landscape starts to look pretty good for Romney in the weeks ahead. Santorum will probably do well in Louisiana on Saturday, but then a slew of northeastern primaries look like almost-certain Romney wins: Maryland, Connecticut, New York, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Washington, D.C. Three of those states are winner-take-all states, which means Romney will take all the delegates on the table. Santorum will win Pennsylvania, but his struggling campaign needs more than a home-state win. And the Pennsylvania primary will not be all gravy, as it will offer the Romney campaign a chance to remind people how badly Santorum lost that state in his last Senate election.

Mitt Romney won in Illinois the way front-runners are supposed to win. Still, if his opponents don’t get out of the race, it could be two more months of slow, steady victories before he actually crosses the finish line with 1,144 delegates. He should buy a few more shirts.