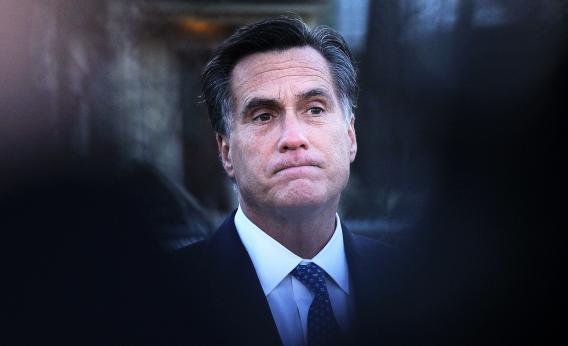

Who says Mitt Romney isn’t exciting? He’s making the Republican presidential campaign really exciting. Every time he seems within reach of locking down his gains and retaking his place as the inevitable nominee, his campaign hits a rocky patch.

Romney won the Ohio primary by a prosciutto-thin margin, given that he out spent his rival Rick Santorum by 4-to-1. The victory in the most coveted Super Tuesday contest was the story of disaster narrowly averted. Santorum could tell a story of defying the odds and marvel at how far he’d come. He won three of the 10 races—with victories in Oklahoma, North Dakota, and Tennessee—and nearly claimed the big prize with a campaign operation held together by bailing wire and sturdy boards found at the roadside.

The Republican presidential campaign is now a battle between a movement and mathematics. Santorum has the energy and support of the noisy part of the party—the Tea Party stalwarts and evangelicals for whom conviction and shared values are everything. Romney’s ugly win in Ohio only continues to raise doubts about the soundness of his enterprise: Is he only ahead, eking out these victories, because he has an enormous advantage in money and organization, two things he won’t have against Barack Obama?

But let’s not get carried away by the cinematic drama of the underdog story on the main stage. Romney won six states and a whole lot of delegates on Super Tuesday. What Romney has going for him is the math and that’s what will ultimately determine the nominee. He leads in the delegates—more than twice as many as Santorum—and is likely to keep that lead even if his victory trophies require tweezers to hold them aloft.

Before the Michigan primary last week, Romney said he wasn’t willing to light his hair on fire to win the election. But in looking at Tuesday’s exit polls, he must at least be ready to pull his hair out. Fifty-four percent of voters said the economy was the most important issue in determining their vote, and they voted for Romney by 41 percent to Santorum’s 33 percent. Forty-two percent of voters in Ohio said they wanted a candidate who could beat Barack Obama. That was the top quality they sought in a candidate. Romney won in that group 52 percent to 27 percent. Voters also said they preferred a candidate with business experience over government experience by 64 percent to 27 percent.

All of that would suggest a big Romney win, right? Nope. Voters want something else, too. In Ohio, the other half of the electorate cared about who was the true conservative, and Santorum crushed Romney 51 percent to 13 percent on that score. The 21 percent who cared about moral character likewise went for Santorum by 40 points over Romney, 60 percent to 19 percent. Ohio voters also felt like Santorum shares their concerns more than Romney, a big problem for Romney in a key bellwether state. The state has picked the president since 1964. The Republican candidate will have to beat Obama on that important economic question. That Romney can’t convince members of his own party—particularly blue-collar voters he’ll need in the general election—is not a good sign.

If Romney couldn’t claim roaring support in Ohio, it was hard to do so in the other places where he notched sure victories. He won in Virginia, where Ron Paul was his only competition. In Idaho, Mormons put him over the top. Massachusetts is his hometown and Vermont its neighbor. Good for the math but not momentum. Perhaps that’s why Romney sounded more determined than elated Tuesday night. “Tomorrow we wake up and we start again. And the next day we do the same,’’ he said. “And so it will go, day by day, step by step, door to door, heart to heart. There will be good days and bad days, always long hours, and never enough time.’’

The Romney campaign is now going to start talking about Mitt Romney’s favorite topic: numbers. They will argue that, after tonight’s contests, the governor will have a lead in delegates too big for his opponents to overcome in future contests. The experts say this too, by the way. As well as Santorum may have performed, he is even more limited than Romney in his ability to reach outside the very conservative base of his support.

Santorum will not be on the ballot in the District of Columbia and won’t compete for a full slate of delegates in Illinois. In the future states that are winner-take-all, like Utah, Delaware, and New Jersey, Romney has strong organizations, and the electorates are more favorable to him. Even in states like Tennessee and Georgia where Romney lost, he was able to draw some delegates, making it harder for his opponents to overtake him.

Santorum is going to start feeling the pressure from Republicans who say he should hang it up to keep from damaging Romney too much. The math is inevitable, so all he’ll do is weaken Romney in his ultimate contest against Obama. Romney is already suffering from the bruising primary battle. In the latest NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, Romney’s unfavorable rating has grown to 39 percent. His favorable rating is only 28 percent. The longer the battle drags on, the less time Romney will have to raise money and repair the damage done by the primaries.

The Romney campaign never wanted to be seen arguing that Romney was inevitable. Now they’re doing just that. It’s a version of the argument that the Obama campaign made in 2008 when it tried to get Hillary Clinton to turn around her campaign bus. The key difference is that Barack Obama was filling stadiums of rabid supporters at the time. Mitt Romney is not burdened with this problem.

“That’s not a very inspiring message,” said Santorum spokesman Hogan Gidley of Romney’s claim of mathematical certitude. Santorum’s aides argued after the close call that if it were a head-to-head contest (i.e., no Newt Gingrich), Santorum would have won in Ohio and would go on to win future states. Regardless of Gingrich’s decision, Santorum’s aides say he will stay in the race to be a voice for conservatives who they say are still suspicious of Romney. Thirty-eight percent of voters said Romney’s positions were not conservative enough, the highest of any of the candidates. (Only 17 percent said that of Santorum.) Forty-one percent of Ohio voters said they had reservations about the candidate they supported. Of that group, 42 percent felt that way about Romney. Of course, Santorum can’t go too far with this. Thirty-eight percent of those voters have doubts about him, too.

Santorum tried to give new reasons to be suspicious of the front-runner on Super Tuesday. He highlighted newly discovered videos in which Romney said he supported the individual health care mandate that is the central horrid element for Republicans in Obama’s health care plan. Romney has said he never advocated for an individual mandate at the national level. Not once. Not even in a joke alone before bedtime. But the videos suggest otherwise. “We need a candidate who can be honest with the American people,” says Santorum. The Pennsylvania senator has long claimed that Romney’s support of the individual mandate made him an imperfect messenger in a battle with Barack Obama over his health care plan. Now he’s turning up the attack: He’s saying Romney is dishonest.

Santorum will press this case all the way to the convention, say aides. The hope is that the senator will be able to win enough contests to deny Romney the 1,144 delegates he needs to win the nomination. If they can make it to the convention, they’ll fight it out there, trying to persuade unpledged delegates. The next set of contests in Kansas, Mississippi, and Alabama have lots of socially conservative and evangelical voters who have been cool if not hostile to Romney. Romney will have to endure a stretch where movement conservatives may appear stronger than the party regulars who rally around his mathematical candidacy of inevitability.

On Super Tuesday, Romney won the second hard-fought primary in a row, a first for this Chutes and Ladders campaign where every time a candidate skips his way out of the winner circle, he falls in the next contest. But the games aren’t over. And, unfortunately for Romney, neither is the excitement.