Mitt Romney reminds voters at every campaign stop in Michigan that he is a local boy. He points out school friends, the cemetery where his parents are buried—his father picked the plot because it was the cheapest—and talks about vacations they took in his family’s rambler. In Traverse City on Sunday, he delighted the packed house on how he stole his first kiss from his wife Ann on a beach down the road. It seems to be working. “He’s a lot less stiff,” says Bill Vettel after hearing Romney speak Saturday at a college in Flint, Mich. “He’s more like someone you could like.” Sunday, after a well-attended Traverse City rally, Marve Schrebe is energized by Romney’s performance. “If he would come on television and make a presentation like this one and unleash his soul, it would be great!”

Rick Santorum can’t claim local roots, but he speaks to voters where they live, channeling their anger and frustration with government. His audiences shout out in agreement as he highlights the Obama administration’s disrespect for people of faith or its disregard for the Constitution. They react with gasps when he lists the most recent offenses to the traditional American way of life. “I like his values and passion,” says Marge McCulloch. Most voters who support Santorum say the same thing: They like his personal qualities.

Trust me, I’m one of you.

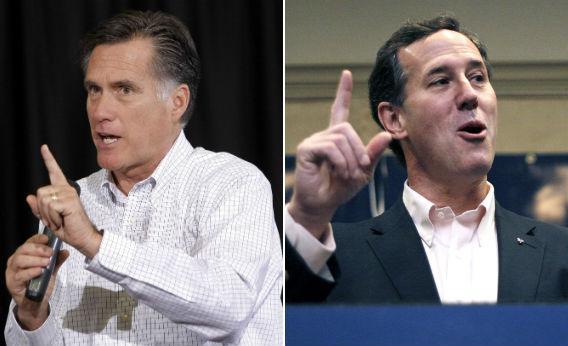

Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum are offering a different version of the same message. The polls in Michigan show that the race is essentially tied. Both candidates say they are the true conservative. They both promise to tell the truth. They say their opponents will waiver under pressure. Why should a voter think either one is on the level? A shared connection—either of conviction or background—might make the difference. He is one of us. He won’t let me down.

In the battle to pitch themselves as the true conservative, Santorum clearly makes the stronger case. In Traverse City Sunday night, he was introduced to the crowd as a “warrior for life.” The first half of his hourlong speech was a defense of religion in public life. That morning he had defended his comments that John Kennedy’s speech about the separation between church and state had made him want to throw up. “That is France, not America,” he said of Kennedy’s claim. “Look what happened in France. A group of people who now no longer have to respect anybody’s rights, it’s whatever the government says you have the right to is what you have the right to. [It] results in tyranny.” That’s the mindset of the Obama administration, he claims. “They are also going to force people of faith to adopt their secular values, that if people of faith don’t agree with the secular values of this administration then you will be punished.”

Santorum praises the Tea Party and wraps himself in their message of returning to the Constitution, but it’s a bit of sleight of hand. Tea Party supporters are almost totally focused on shrinking government. That’s not Santorum’s message. His pitch is about values. “He is a Christian,” says Art Bak, the owner of a flag company. “He upholds Christian principles our country was founded on.” Scott Johnson, who wrote a check to Santorum for $100, said he wants Santorum to help “bring back the old United States.”

Santorum is pugnacious, describing a president who sniffs at the things they hold most sacred. “The President of the United States said the other day that every child in America should go to college. What a snob.” Santorum says the administration is mocking them. “You will be fined. You will be held up for ridicule,” he says of health care provisions that conflict with religious views. “Never before in the history of this country have we seen anything like this. Yet the president sort of laughs it off.”

A Romney staffer attending the Santorum event quips that he didn’t talk about jobs for the first half-hour. It’s true, and Santorum can hardly blame the media for making him talk about social issues. He’s clearly choosing to hammer away on social issues in Michigan. It makes sense, though. He’s setting the hook. With an audience alive to the mingled threats from the Obama administration’s overreach, he then pivoted to Romney, explaining why he is too weak for such a dire moment. He won’t be able to draw a contrast with Obama because Romney’s Massachusetts health care plan, support for the Wall Street bailout, and belief in global warming make him too similar. That’s what makes Santorum more electable. “I like this term resolute that he used the other night,” he says, speaking of Romney. “Maybe he doesn’t understand what the term resolute means. But it means that you’re supposed to have sort of a resolve, a consistent pattern of beliefs.”

Santorum’s reasoning about Romney is reaching his audience. “Mitt Romney has too much baggage,” says Bob Hammond, a 63-year-old civil engineer. “If Mitt Romney is the candidate, the comparisons between Romneycare and Obamacare are too great. It wouldn’t be a very good distinction.”

Santorum goes on for over an hour. His argument is methodical, but he feels like a talk show host filling time. He cycles through one outrage after another and sometimes seems to be just riffing, showing the audience how clever he is. “Imagine if we had insurance that covered food,” he said during an extended lope through an analogy about government intervention in private choice in the health care market. “And you paid—you know, instead of Blue Cross and Blue Shield, you had Blue Cow and Blue Pig … .You think we have an obesity problem now?”

He tries to make a virtue of his lack of polish, making a clear reference to Romney’s overly precise campaign. Santorum says his personal approach is a more authentic one. “I never have to worry about what I say because I will say what’s [in] my heart. I might not say it the most articulate sometimes and I understand that, but I have no teleprompters. I answer questions from the public in front of cameras. I answer questions from the press every day. I don’t hide. I don’t hide from the public. I don’t have structured events where only my friends are in front of me to take questions. When someone doesn’t agree with me, I tell them that answer even if they don’t want to hear that answer because you know what, they’re entitled to the truth.”

Across town two hours later, Romney draws about 150 more people than Santorum’s 500 or so. He is sharp and relatively brisk, speaking about a third as long as Santorum. He makes the same point about the threats to the American Dream. He recites verses from “America the Beautiful” to kindle patriotic sentiment as he has for months now. The language echoes Santorum’s language: “The creator had endowed us with our rights, not the state, not the king but the creator and that we would be a state that trusted in God. We would be one nation under God.” But at a Santorum event, the audience would have cheered the use of the word God, seeing it as an argument against those who would deny His place in the American experiment. At the Romney rally, the line gets no response. It’s boilerplate, not bomb throwing.

Romney voters care about electability, which is why the candidate makes the pitch explicit. “I’m the only guy in the race who can beat Barack Obama.” After his events, Romney’s ability to beat Obama is cited by every voter I meet. The biggest reaction Romney gets is when he says, “This is a president who is out of ideas, out of excuses, and in 2012, he’s going to be out of office.” It’s not that Romney delivers the line that well. People are just excited to imagine a world without Obama.

Romney appears to be making some headway by highlighting Santorum’s ties to Washington. Santorum says Romney is just a manager who wants to tinker with Washington instead of change it. Romney makes the same charge. “My team is the people of Michigan and America and I’m going to fight for you. If you want to send someone to Washington who is working around the edges to make little changes here and changes there and work with this subcommittee and that subcommittee, then there are plenty of other people to choose. But if you want someone who will fundamentally change Washington, and bring us more jobs and less debt and smaller government, then I’m your guy.”

Santorum is also too conservative for some Romney voters. “He is way out there. He’s as far right as Obama is left,” says Ann Vettel from Flushing, Mich. ”I’d love him for my minister, but he talks too much about personal things. Personal things don’t run the United States.”

Both candidates are pitching radical change, but Mitt Romney’s is a far more comfortable brand of radicalism. It doesn’t come in radical packaging. It doesn’t seem off topic. He’s talking about jobs and spending, not whether colleges turn people into radical atheists or some speech President Kennedy delivered 50 years ago.

If Mitt Romney doesn’t win Michigan, it will be devastating. He has so many advantages in the state. He has much more money, a better organization, and biographical ties. Rick Santorum’s lack of discipline and weak debate performance also give Romney an opening. If he can’t win here, his argument about how those advantages will help him capture future states will seem absurd. Even if Romney is able to win in a safe state—which, in truth, may now qualify as a comeback state—the questions about his candidacy and ability to appeal to conservatives will not die in Michigan. In states where he doesn’t have personal ties, his appeal has come across with all the sincerity of a LinkedIn invitation. No one ever became president without his party regulars thinking he is one of them.