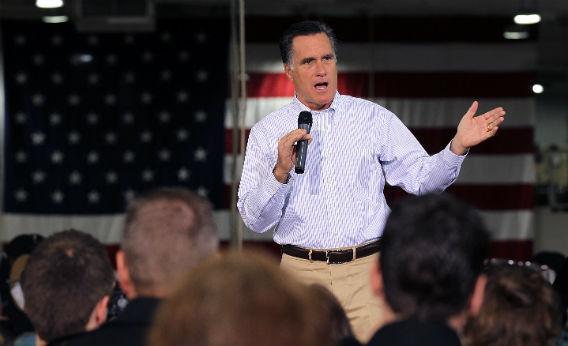

FLINT, Mich.—Mitt Romney’s advance team has a simple mission: Make the candidate look like he’s already president. Maybe he was sworn in when you weren’t paying attention. To see him, you had to sign up with the campaign, show up early, prove your harmlessness to the Secret Service, and find a place in a theater-in-the-round set-up where the candidate is flanked by whale-sized American flags.

Romney showed up in casual chic: dress shirt, blue jeans, dress shoes. The speech took advantage of only a third of the room—curtains clipped off the rest of it—so the crowd, mustachioed security, and media pen were pushed together for maximum effect. (Clearly, the campaign had learned its lesson from the less-than-epic staging of his Friday economic speech.) Romney paced the stage in front of a bleacher full of Kettering University students.

“Kids can’t find work,” said Romney. “This is something I’ve heard Dick Armey say: It used to be that the American dream was owning your own home. Now, the American dream is getting your kids to move out of your home!”

The Kettering students, serious-looking in matching gray T-shirts, did not laugh. The rest of the crowd did. They were being asked to whipsaw between jokes like this, brief descriptions of what he’d do in office, and patriotic musings on the common man.

“Everywhere I go, I see people who love this country,” said Romney. “I’m proud of the fact that when we perform the national anthem, we put our hands on our hearts.” He put his hand on his heart. “The reason we do that is to honor the blood that has been shed by those who have sacrificed for liberty.”

Romney’s pitch to this crowd was hardly different from the pitch he’d used in Iowa and New Hampshire. The stakes were very different there. In Iowa, he only needed to avoid falling far below his 2008 numbers—he basically tied them. In New Hampshire, he had to rack up a huge vote to prove that he’d gained ground since he lost to John McCain.

Michigan, though—Michigan is different. After Rick Santorum won two caucuses and a “beauty content” (no delegate) primary, he moved ahead of Romney in Michigan primary polls. No one had bested Romney in those local polls since 2009. Santorum adviser John Brabender has said his candidate “already won” here, because he’s forcing Romney to hustle in the place where he was born. A lot of campaign spin is self-evidently ridiculous. Brabender’s spin is not. Even if Romney wins here, Republicans already want to know why he’s struggling.

There’s no new reason. Romney’s weekend blitz of the state took him to wildly different segments of the GOP base. He was very comfortable with one of them: well-groomed, well-heeled Republicans, the kind that run local party organizations and clap awkwardly to Bob Seger songs. The others—the sort of people who either rebelled against the “establishment” in 2010—didn’t hug him so close.

Romney’s Saturday started off well. He was the star of the Ingham County Lincoln Day breakfast, an eggs-and-coffee-and-county-commissioner-placards affair in the dining room of a Lansing, Mich., country club. Before he spoke, Republicans heard “The Star-Spangled Banner” sung by the Old School Fellas, a zoot-suited amateur doo-wop group. “Mitt’s a good, Christian man like I am,” explained Clinton Tarver, wearing the reddest of the zoot suits.

Romney spent five of his 25 minutes reminiscing about the state. “I remember my dad’s first inauguration,” he said. “As I recall, it was a snowy day. A very cold day.” He spotted a friend in the crowd. “You were there! As I recall, they’d just changed the slogan of the state, on license plates. It had been Water Wonderland. They changed it to Winter Water Wonderland. It was hard just to say it!”

He had less to say about the Michigan of 2012, specifically. His stories of economic woe came from people he’d met “all over the country,” like in New Hampshire, where an elderly barber told him he couldn’t quit yet. “I talk to retired couples who thought these would be the best years of their lives. Instead, they have to work.”

The room was packed with Romney endorsers. Half the room stuck around to try and press flesh when he finished. He loaded up on positive vibes, because he was about to head 70 minutes east to Troy, Mich. Romney had to follow Rick Santorum at a one-day seminar put on by Americans for Prosperity (AFP), the best-funded of the Tea Party mega-groups. (Democrats never miss a chance to remind you that David Koch helps fund this one.)

We weren’t in Romney country anymore. Michigan’s Republican governor, Rick Snyder, had just endorsed Romney. AFP was passing out fliers warning that Snyder wanted to “raise your gas prices,” portraying him cold and uncaring in front of an expensive-looking pump. (The governor supports a higher gas tax.) Santorum had just called Barack Obama a “snob” and Romney a simp who “adopt[ed] the verbiage of Occupy Wall Street.” Santorum had completely won the room over. Columnist Michelle Malkin, speaking after him, accidentally re-endorsed him from the stage. (This is frowned upon at nonpartisan, educational AFP events.)

Romney had a tougher time of it. Watching him sell himself as a conservative was like watching Jack Lemmon’s character in Glengarry Glen Ross try to sell overpriced plots of real estate. “I was in business for 25 years,” he said. Mild applause. “I will cut spending, I will cap spending, and I will finally balance the budget.” Louder applause, no real rapture. The real sirloin in the speech was a long section trashing Rick Santorum as a phony conservative. Romney pointed to Santorum’s debate performance as proof that he couldn’t be trusted—he “took one for the team,” he would fold again. But proving this case meant providing examples. “He voted for No Child Left Behind,” said Romney. “I favored that, by the way, but he was opposed to it, and he voted for it.” Strong stuff.

Another tack: “It was also in 1996 that [Santorum] supported Arlen Specter, by the way. Arlen Specter, the only pro-choice candidate we’ve seen in that race. There were other conservative candidates running, like Bob Dole. He didn’t support them! He supported the pro-choice candidate.”

Bob Dole? The conservative candidate? The guy Santorum and Gingrich mention as proof that Republicans never win if they pick compromisers? As Romney struggled, Andrew Breitbart paced near the table where organizers had parked a coffee carafe on top of a slowly browning white tablecloth.

“I despise the left because I despise the political correctness they apply to everyone and everything,” said Breitbart. “I see the same thing happening on the right with this campaign. You don’t support Ron Paul, you’re not a conservative. You don’t support Santorum, you’re not a conservative.”

Breitbart was describing Romney’s problem perfectly. Romney’s allies in the state can’t really disagree with his analysis. Rep. Bill Huizenga, a freshman Republican who represents one of the districts Romney carried in 2008, told me that the voters would come around, slowly.

“You’ll hear people clap when Santorum talks about right to work,” said Huizenga. “That’s one of the issues he’s the worst on? Look, I like Rick Santorum. I just don’t think he can win in November. Voters are going to learn more about him and figure this out. He’s getting a boomlet, like all of these other candidates had boomlets with Republican voters. Herman Cain wasn’t perfect. Michele Bachmann wasn’t perfect. Rick Perry wasn’t perfect. They’re looking for perfect. Perfect isn’t showing up right now.”

As they filed out of Romney’s speech, the AFP Tea Partiers were still waiting for perfect. They buzzed about Santorum, not the guy who was born a few miles away. And Romney was ending his day in Flint, in front of a mixed crowd, not overwhelming in size, supportive but not thrilled. He closed the speech by starting to talk up his electability. Polls show that Republicans are far more confident that he could beat Obama than they are about the new phenom from Pennsylvania. It’s the Romney trump card.

“I think I’m the only guy in this race that will be able to beat Barack Obama,” said Romney. “And why is that?”

The crowd interrupted Romney with cheers.

“We’ve got to get that job done,” said Romney.

He didn’t actually explain “why” he was electable. He just started asking for people to turn out on Tuesday and vote. The crowd didn’t need an answer. Because these Michigan voters know that they are the ones who will choose to make him electable.