In 1925, a successful advertising executive wrote a wildly popular book that depicted Jesus Christ as the ideal American businessman. Bruce Barton’s The Man Nobody Knows imagined a strong courageous, Republican-leaning leader of men. He was handsome, resolute, and his “muscles were so strong that when He drove the moneychangers out, no one dared to oppose him!” The publication of The Man Nobody Knows is arguably when a prototype of Warner Sallman’s strong-jawed all-American visage of the Head of Christ took its place in American popular culture. Although Barton’s opus is long forgotten, his book had a political impact we can still see evidence of today. It helped install American businessmen into the pantheon of great American leaders.

Indeed, Barton’s vision came to life three years after his book’s publication. Herbert Hoover, who made his fortune in the mining business, was the first big test of Barton’s leadership model under the national spotlight. (Barton is said to have personally liked Hoover, and supported his candidacy.) In Hoover, here was a man, as American novelist Sherwood Anderson observed, who acted as if he has “never known failure.” Hoover was a successful food relief administrator in World War I, famous for relieving hunger in Belgium. He was internationally respected for his humanitarian work. In the lead-up to the 1928 election season, Hoover emerged as the most electable candidate, a progressive Republican set apart from the conservative fringe. He avoided the culture warmongering social issues of the mid-1920s (like the Scopes trial), preferring to focus on his reputation and experience in “offering solutions of various national problems.”

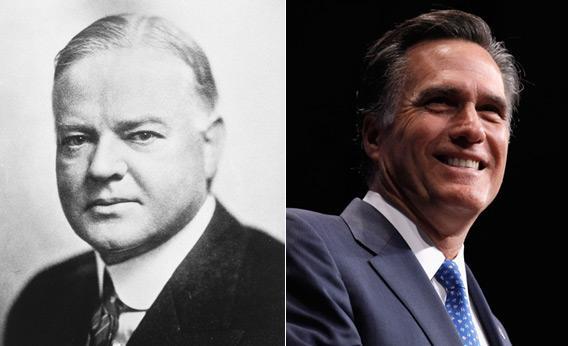

The comparison is now pretty obvious. Hoover was, in other words, a lot like Mitt Romney. Both men sought to leverage their business experience and competence as executives into the Oval Office. Hoover, like Romney, believed that the government existed to facilitate cooperation and trust with the private sector to solve problems. He campaigned on the notion that a bureaucratic government in the business of direct federal assistance would only threaten America’s unique spirit of individualism, and stifle initiative. Romney talks a lot about his plan for his first day of office, when he will issue “a series of executive orders that gets the U.S. government out of the economy’s way.” While Hoover talked about his administration of food programs during the war, Romney leans heavily on his (admittedly less dramatic) management of the troubled Salt Lake City Olympics. Of course, Romney has one thing on Hoover: He looks the part. His strong jaw, large frame, and perfect hair are a lot closer to Barton’s imagined ideal.

No one remembers that in 1928 Hoover won in a landslide. His four years in office are the epitome of a failed presidency. In the end, his name was more closely associated with “Hoovervilles”—the Depression-era shantytowns of the homeless—than business acumen and competence. And the bad taste left in everyone’s mouth has lingered. In 84 years, despite many opportunities, American voters have never put another accomplished businessman in the White House. The Hoover curse reigns.

Will Romney be the one to break it? Who knows? Right now the Massachusetts Republican is fighting hard to win his party’s nomination. Even if he succeeds in the primaries, Barack Obama, a far more formidable opponent, is waiting in the wings. For better or for worse, Romney’s campaign has chosen the candidate’s business experience as its fulcrum, and in doing so, Romney has set out to portray himself as the ideal man for the job in a sea of politicians. To be fair, Romney’s resume is broader than the one Hoover offered. Romney has already served in elected office as governor, and this political experience may be a helpful antidote to the decades-old curse against businessmen.

Even if 2012 ushers in a Romney presidency, Mitt and his team will want to exorcise the Hoover ghost by having a successful four years. And there, too, they should bear in mind what historians say sank Hoover once in office. As David M. Kennedy has pointed out, one of the leading causes of Hoover’s political demise was his inability to control his party. Hoover may have had the reputation as a competent, powerful businessman with an engineer’s mind, but he didn’t have the personality to go with it. Starting with the disastrous Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act of 1930, which raised international import duties to record highs, Hoover contradicted his own personal political convictions and gave in to pressure from his party leadership on major points of policy. Even when faced with a petition of 1,000 economists begging Hoover to veto the bill, and a visit from Henry Ford himself, Hoover signed Hawley-Smoot into law. The disastrous results—both for Hoover and the country—are well-known.

Romney’s early troubles on the campaign trail suggest he may not have the personality to unite his party either. At least, many Republican party leaders think so.

At the CPAC convention two weeks ago, Grover Norquist had this to say:

We are not auditioning for fearless leader. We don’t need a president to tell us in what direction to go. We know what direction to go. We want the Ryan budget. … We just need a president to sign this stuff. We don’t need someone to think it up or design it. The leadership now for the modern conservative movement for the next 20 years will be coming out of the House and the Senate.

That doesn’t bode well for a man looking to kill an 84-year curse.