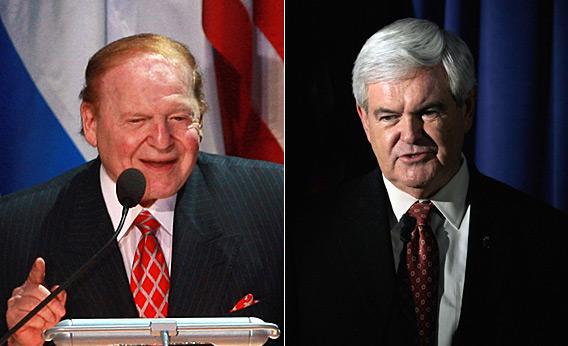

Anyone who counts out Newt Gingrich after his lackluster performance in Thursday night’s Republican debate is overlooking an important fact: He has the support of perhaps the most lavish individual donor in the history of presidential politics.

Rewind to three weeks ago. Gingrich’s campaign was sagging after back-to-back fourth-place finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire. Ordinarily, that kind of performance sends donors fleeing and dooms a campaign. But Sheldon Adelson, the nation’s eighth-wealthiest person, is no ordinary donor. Against the advice of pretty much everyone, the Las Vegas-based casino tycoon and hawkish Israel backer singlehandedly revived Gingrich’s campaign with an astonishing $5 million donation (by far the largest of the campaign cycle) to a pro-Gingrich committee. The Winning Our Future super PAC quickly spent a chunk of the cash on television ads bashing Mitt Romney in South Carolina. Gingrich won the state in a landslide.

After that, Adelson doubled down. His wife, Miriam Adelson, splashed out another $5 million for the super PAC to spend in Florida, bringing the couple’s contributions to $10 million in the space of two weeks. That’s more than the Gingrich campaign raised from all of its direct donors combined in the fourth quarter. The Associated Press, not typically given to superlatives, reported that the two gifts ranked “among the largest known political donations in U.S. history.” Just how large are they? And could they, in fact, be the largest in U.S. history?

Depending on how you count them, yes. But it’s easy to see why the AP kept its assertion vague. To search for a definitive answer is to plunge into the shadowy, convoluted history of American campaign finance.

In sheer dollars, the largest gifts ever came in the 2004 campaign cycle. At a time when Democrats were terrified that George W. Bush’s Republicans had figured out how to rig the game in their favor, some of the world’s richest liberals placed their diamond-encrusted thumbs on the other scale. That year, financier George Soros gave a combined $23.7 million to federally focused political action committees, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Though that’s the most anyone has ever given in a single campaign cycle, others were close behind. Peter Lewis, chairman of Progressive Insurance, also gave more than $23 million to liberal 527 groups that year. Shangri-La Entertainment’s Steve Bing and the Sandler family of Golden West Financial topped the $13 million mark.

Ironically, that 100-year flood of largesse came just two years after the passage of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance reform act. Meant to crack down on “soft money” gifts to political parties, the bill pushed big donors instead to the 527s, with no limits on how much they could give. But there’s a difference between the 527s of 2004 and today’s super PACs. Back then, unlimited gifts could only go to committees engaged in “issue advocacy” or “voter mobilization.” The groups were barred from endorsing a particular candidate.

Not that they couldn’t find ways to influence a particular candidate’s chances. Among the most notorious 527s was Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, dedicated to smearing Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry’s reputation for valor in the Vietnam War. Few paid attention to the group when it launched. But after Texas financier Bob Perry handed it $4.5 million to spend on TV ads, the whole country took notice. Because of the Swift Boat group’s deviously effective strategy, Perry’s bucks made a bigger bang than the tens of millions that liberals like Soros gave to more broadly focused Democratic voter-turnout organizations like America Coming Together.

If Adelson’s Gingrich gifts aren’t the largest political contributions in American history, might they be the biggest gifts dedicated to a single candidate’s campaign? In nominal dollars, perhaps. When you adjust for inflation, however, the free-spending donors of the pre-Watergate era—a time when individuals could give unlimited amounts directly to candidates’ campaigns—might have the edge. On the Democratic side, the biggest spender was philanthropist Stewart Mott, who gave $200,000 to anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and $400,000 to George McGovern in 1972. Both amounts equate to more than 1 million today.

But these sums were dwarfed by those of W. Clement Stone, the insurance magnate and self-help author who propelled Richard Nixon’s campaigns in 1968 and 1972. His gifts, chronicled in Herbert E. Alexander’s books Financing the 1968 Election and Financing the 1972 Election, included a then-enormous sum of $500,000 in the 1968 Republican primaries, a payout that helped Nixon defeat Mitt Romney’s father, George. In 1972, Stone’s contributions to Nixon in the primary and general elections totaled an estimated $2.1 million—upward of $11 million in today’s dollars.

Still, Stone’s money was arguably less influential than Adelson’s. While some of his 1972 gifts came in the primaries, more came in the general election, where it formed a smaller slice of Nixon’s total pie. Even so, the donations were outrageous enough at the time that they sparked the country’s first major overhaul of campaign finance two years later. Since 1974, direct gifts to candidate’s campaigns have been strictly capped, forcing those who want to buy influence to do it indirectly.

For those who think modern campaign finance is shady, consider the climate just before the turn of the century. Perhaps more than any other president, William McKinley was seen as a puppet of big business interests—and justifiably so. Campaign finance expert Anthony Corrado, a professor of government at Colby College, reckons that McKinley spent at least $3 million in each of his successful presidential runs, in 1896 and 1900. With the help of the legendary Republican Party organizer Mark Hanna, McKinley’s campaign collected money from the barons who ran the banks, railroads, oil companies, and trusts, with each asked to fork over cash in proportion to his company’s “stake in the general prosperity of the country.”

Among the deepest-pocketed donors of the time was E.H. Harriman, a railroad owner whose name will be familiar to anyone who’s seen Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Another big McKinley spender was Henry Clay Frick, the steel man and namesake of one of New York’s famous art museums. Just how much did they give? No one knows, because there were no disclosure requirements.

As with the pre-Watergate boom years, these fin de siècle excesses gave rise to reforms. In 1907, Teddy Roosevelt signed the Tillman Act, which restricted corporate contributions to campaigns. Decades later, the rise of big union donations to Franklin D. Roosevelt spurred limits on union spending as well.

If there is an apt superlative for Adelson’s donations to Gingrich, Corrado says, it’s this: Never, that we know of, has an individual propped up one candidate’s campaign to such an extent. That is, an individual other than the candidate himself—candidates have long been allowed to bankroll their own campaigns, a fact that has favored ultra-rich hopefuls like, well, Mitt Romney. Romney has in fact significantly outspent Gingrich in the current campaign, even counting the Adelson money.

Reforms have changed the ways people give, and they have often suppressed the influence of money in campaigns for a time after their passage. But if there’s one recurring lesson from the history of campaign finance reform, it’s that big money always influences the process one way or another.

Bradley Smith, a member of the Federal Election Commission from 2000 to 2005, takes that as an argument against campaign finance reform. Now a law professor at Capital University in Ohio, Smith argued for the plaintiffs in a 2010 federal appeals court case that laid the groundwork for super PACs in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision. A First Amendment absolutist, Smith opposes even disclosure rules as invasions of privacy. Senate Republicans seem to agree: They blocked a bill last year that would have required super PACs to name their top donors when advertising on television. (There’s now talk of resurrecting it.)

The current rules at least make it possible to find out where Newt Gingrich’s money is coming from—an improvement on McKinley’s day. When he talks tough on Palestine, it’s fair to question whether he’s espousing his true beliefs or parroting a line from his benefactor. There’s no question that Gingrich has been paid for by Sheldon Adelson. It’s up to voters to decide whether he’s been bought.