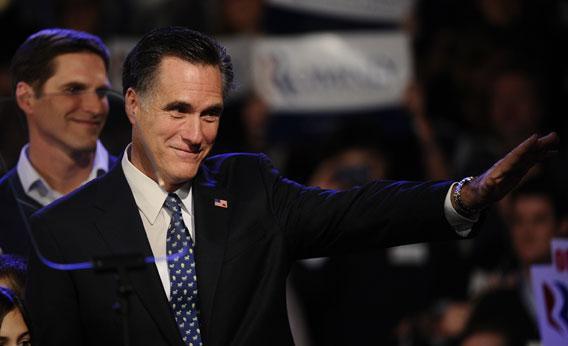

For the last week, Mitt Romney has called himself “landslide Romney,” repeating a joke from John McCain about his eight-vote victory in the Iowa caucuses. The title fits a little better now. He won the New Hampshire primary by a handy 16 points with 39 percent of the vote. In the much-watched fight for runner-up, Ron Paul got that “real nice second place” he’d been predicting, with 23 percent of the vote, and Jon Huntsman finished third with 17 percent—to the disappointment of New York magazine editors but few Republican voters. [Updated 11 a.m., Jan. 11.]

Mitt Romney has been an anemic candidate, ahead in the polls but not strong enough to lock up victory. Will New Hampshire put some iron in the blood, or is it a pale win that won’t quell conservative calls for a nominee they can believe in? Romney is now the first nonincumbent Republican candidate in history to win the Iowa caucus and the New Hampshire primary, and he can expect a bump in the polls in South Carolina and Florida, where he is already ahead.

Romney calls himself a “numbers guy,” but by the numbers he has a tremendously long way to go. He has won only handful of delegates. Even after the first four contests, only 15 percent of the delegates will be apportioned. Romney is banking that his wins create a bandwagon effect, drying up the money of his competitors and shrinking the appetite for the anti-Romney candidate. He is in essence hoping for the surge that has lifted every other candidate in this race except him.

Expectations were high for Romney, and he met them. Thirty-five percent of New Hampshire voters said their most important issue was beating Barack Obama. Romney won 60 percent of them. Romney carried all groups—from Tea Party supporters to conservatives to moderates. Despite this week’s attacks on Romney’s tenure at Bain, voters still seem persuaded by his argument that his business experience makes him the best candidate to handle the economy. Among the 6-in-10 voters for whom the economy was the top issue, Romney more than doubled the support of his nearest competitor.

Ron Paul won handily among young voters, getting 40 percent of the 18-29-year-old vote. He also won with voters who said voting for a “true conservative” was what motivated their vote. Paul grinned to his supporters at his election night party, and he reveled in being called ”dangerous.” Mitt Romney won handily, he said, “but we’re nipping at his heels.” But even if he was nipping, the exit polls showed Paul’s limitations. 55 percent of those polled in New Hampshire said they would be dissatisfied if he won the nomination. Only 37 percent said that about Romney.

In South Carolina, which votes a week from Saturday, Romney can expect 10 days of hell. South Carolina is likely to be the last stand of the anti-Romney forces, or the place where they turn the tide. Romney is likely to be the target of sustained attacks that may be last serious assaults of the primary-season nomination battle if he does well there.

The Romney campaign is hoping that New Hampshire will validate him and sweep away the stories about Republicans unhappy with the front-runner. In the latest CBS national poll, 58 percent of Republicans say they want more presidential choices. Romney leads that poll but with only 19 percent. In exit polls of New Hampshire voters, 31 percent said they wanted another candidate to join the race.

New Hampshire may end up acting as a shield for Romney against the recent attacks on his business career. Newt Gingrich, Rick Perry, and Jon Huntsman characterized Romney as a ruthless corporate raider. Though the attacks started too late to change the New Hampshire result much, Romney can claim that New Hampshire voters heard them and decided they were without merit.

It’s not clear who will go hardest after Romney now. The problem traditionally with attacking in a multicandidate field is that you harm the front-runner but you also hurt yourself. You don’t attract his voters—you drive undecided voters away from both the target and yourself. That may be happening to Gingrich, who pressed the case against Romney most thoroughly, and whose super PAC plans to run millions of dollars of ads in South Carolina on the issue. His attacks on Romney’s record at Bain were roundly criticized by conservatives from the National Review to Rush Limbaugh. Romney can’t usually count on such conservatives as his allies. Romney also got a solid from Ron Paul, who said Huntsman, Perry, and Gingrich were attacking the free-market system.

Gingrich won only 10 percent of the vote but vowed to continue his attacks on the front-runner. “We’re going to go all out to win in South Carolina,” he told CNN’s John King. “We think that the contrast between a Georgia Reagan conservative and a Massachusetts moderate is pretty dramatic.” Jon Huntsman also said he would continue his campaign, though South Carolina may be too conservative for him. After all, 40 percent of his New Hampshire supporters said they were satisfied with Obama as president.

Rick Santorum didn’t match the surge he had in Iowa. But his 70 visits to New Hampshire and his Iowa bounce apparently made him a more attractive candidate. Santorum, who tied Gingrich at 10 percent, came in third among late-deciding voters.

On Election Day, Romney enjoyed a movie in relative anonymity with his grandchildren, something he won’t be able to for much longer. The kids saw The Muppets and Romney watched Mission: Impossible. After New Hampshire, he hopes one describes his rivals and the other describes their chances.