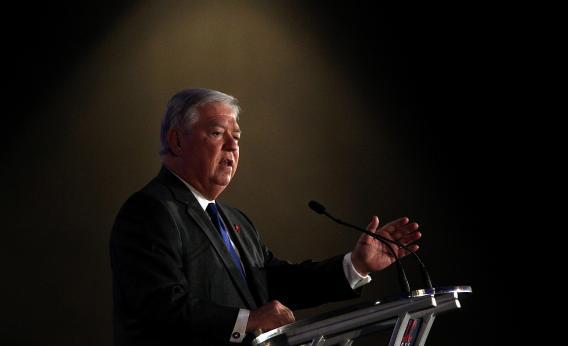

The president’s right to pardon whomever he pleases, without limit or judicial review, is enshrined in Article II of the Constitution. A governor’s right to do the same is also quite sweeping in most states, though subject to a few restrictions. Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour discovered that this week when a judge blocked the release of 21 of the 200-odd inmates he had pardoned in his final days in office, 14 of whom were convicted murderers. (The reason: Some of the inmates did not give the required amount of public notice that they were seeking a pardon.)

The theory behind executive pardons and commutations is that the letter of the law sometimes conflicts with human decency. For instance, Barbour himself was hailed a year ago by NAACP President Benjamin Jealous as a “shining example of how governors should use their commutation powers” after he lifted the life sentences of two sisters who had already served 16 years for robbing someone of $11. In the words of former Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, a presidential pardon amounts to “the determination of the ultimate authority that the public welfare will be better served by inflicting less than what the judgment fixed.”

But we members of the public do not always see how our welfare is being served by releasing convicted swindlers and killers into our midst. On those occasions, we call upon the ultimate authority for some explanation of his or her wisdom. Presidents and governors don’t always deign to answer our calls, nor are they required to do so. But when they do choose to speak out, they give us a window into the various rationales for granting a pardon. Barbour, for one, issued a brief statement saying the “pardons were intended to allow [the convicts] to find gainful employment or acquire professional licenses as well as hunt and vote.”

Below is a rundown of what America’s most notable pardoners have said—and what they really meant.

Thomas Jefferson

What he said: The laws under which these men were convicted were unjust and unconstitutional.

What he meant: The laws under which these men were convicted were unjust and unconstitutional. Also, these men are my political allies.

Upon his election in 1800, Jefferson pardoned all 10 men who remained in prison under the Alien and Sedition Acts, a set of laws passed by his predecessor John Adams in a bid to quell Democratic-Republicans’ opposition to his undeclared war with France. Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, disapproved of the laws on free-speech grounds. But he wasn’t above the idea of prosecuting a few members of the press.

Andrew Johnson

What he said: These pardons are necessary in order to restore peace, order, and freedom to the country.

What he meant: We don’t have the prison space for all these people.

In 1863, as it became clear the Union had the upper hand in the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln made plans to grant amnesty to rebel soldiers as part of a peace deal. His successor, Andrew Johnson, followed through on this promise in 1865, despite opposition from the “Radical Republicans” in Congress, who thought he was going too easy on the South.

Gerald Ford

What he said: Putting this man on trial would be politically divisive.

What he meant: This man just handed me the presidency of the United States.

A month after resigning the presidency, Richard Nixon faced indictment on charges of obstructing justice in the Watergate scandal. His successor, Gerald Ford, put the kibosh on that notion by issuing a pre-emptive pardon. “The tranquility to which this nation has been restored by the events of recent weeks could be irreparably lost by the prospects of bringing to trial a former president of the United States,” he explained.

George H.W. Bush

What he said: This man is a true American patriot.

What he meant: I might have been complicit in this man’s crimes.

The first President Bush came under heavy criticism at the end of his first and only term in 1992 for pardoning former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, who was about to go on trial for lying to Congress about the Iran-Contra affair. Bush said at the time that he felt the trial would amount to a “criminalization of policy differences.” Of course, the fact that Bush himself had been vice president at the time of Iran-Contra might have influenced his thinking a bit. Among those left unconvinced was incoming President Bill Clinton, who declared himself concerned by the implication that “not telling the truth to Congress under oath is somehow less serious than not telling the truth to some other body under oath.”

Bill Clinton

What he said: This man contributes to worthy causes.

What he meant: This man’s ex-wife contributed to Hillary’s campaign.

Clinton offered this as the most important of eight reasons why he pardoned Marc Rich, who had skirted charges of illegal oil deals with Iran by settling in Switzerland. Noting Rich’s donations to Israeli charities and contributions to the peace process, Clinton averred that “foreign policy considerations” militated in Rich’s favor. The pardon, he added, had nothing at all to do with the fact that Rich’s former wife had contributed heavily to Hillary Clinton’s senatorial campaign and the Clinton Presidential Library.

Haley Barbour

What he said: The state parole board agrees with 90 percent of these pardons.

What he meant: The parole board agrees with 90 percent of these pardons. And the other 10 percent worked for me.

The backlash to Barbour’s pardons began when the families of some murder victims learned that their killers had been released from life sentences. Among the first to go free were four men who had worked as “trusties”—domestic servants, essentially—in the governor’s mansion.

Barbour’s rationale here is far from unusual—rather, he’s following a long tradition of politicians capping off their final terms by pardoning people they know personally. Outrage over this practice prompted George W. Bush to refrain from considering personal appeals, instead relying on recommendations by the Office of the Pardon Attorney. But for a prisoner in Mississippi, it seems that your best chance to score a pardon was to get chummy with the man in charge.