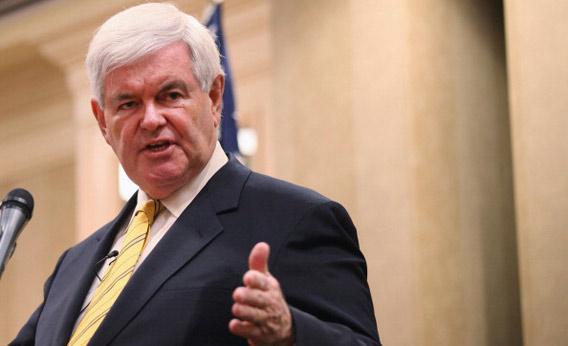

When a presidential candidate makes a promise, it’s always useful to ask: How are you going to pull that off? There usually isn’t an answer. Health care will be repealed, the budget balanced, and 15-minute brownies made in 10. Newt Gingrich is the only candidate who talks about how he would actually enact some of the promises he makes and the changes he would bring to the office of the presidency. Whether you agree with him or not, this is a useful and laudable thing. Candidates should be able to show that they have some concept of how to engage the massively complex organization they hope to take hold of. This would tell us something about them, and force those of us casting votes to be more realistic about what presidents can accomplish.

Gingrich, for his part, has shown that he is occasionally willing to be a realist even when it gets him in trouble with his own party. On the issue of illegal immigration he has made the obvious point that the government does not have the resources to round up 11 million illegal immigrants, and, perhaps more important, from a moral standpoint it is unlikely Americans would support deporting model citizens who have lived in their communities for 25 years. In May, Gingrich criticized Rep. Paul Ryan’s budget plan as “right-wing social engineering” that was too aggressive to win the support of the public. “If you’re dealing with something as big as Medicare and you can’t have a conversation with the country where the country thinks what you’re doing is the right thing, you better slow down,” he said in the first Republican presidential debate.

The gap between the promise and the plan for making it happen is widest in the campaigns of Herman Cain and Ron Paul. Cain sounds like he’s thought about the process of leading when he talks about identifying the right problem and working on it, but his 9-9-9 plan would redesign the tax code essentially on the strength of his personality. All other complexities of governing would be decided by smart advisers. Paul offers even more radical change than Cain with essentially the same promise—that he’ll just make it happen. Unlike Cain, Paul can actually point to his campaign’s organizational successes in support of his argument. If only the world were as easy to organize as a GOP straw poll.

When Gingrich brags about the profound change he’s going to bring as president, he joins a long line of boring politicians promising bold change. But where he differs from the others is that he shows that in small and large ways that he’s thought through just what big change requires. He doesn’t ask his audiences to vote for him but rather to “stand with me.” “If you vote for me you’re going to vote and go home and think Newt will fix it,” he says. Change, he argues, comes only through an entirely new kind of citizenship where people become actively involved in their government again. In his new Contract With America, the third item is a training program for executive branch employees. “You can’t just appoint smart people. You have to have a team and operate as a team, and any corporation would have a training program to acculturate people.”

Every president faces the problem of groupthink. Candidates sometimes promise they’ll seek outside counsel. Gingrich proposes a networked “feedback mechanism” where supporters “can go online and say that say, ‘That didn’t work,’ or a mechanism for you to say, ‘Try this’ if you find something smarter or if the world changes and there’s a new problem, the sooner we talk to each other the better.”

Last week when Gingrich unveiled his Social Security plan for allowing younger workers to invest in the stock market, he offered a strategy for getting it passed. “I wouldn’t make it my program,” he said, explaining why he would succeed where George W. Bush failed. “You can’t come out of an election that is bitterly divided and put your name on a program and think any Democrat is going to vote for it. And I’m not going to go around the country trying to sell it. I’d get hundreds of thousands of young people through social media to decide it’s their program.” (In some narrow minds this would be called “leading from behind.”)

There are some challenges to all of this nifty thinking about the structures to convey change. It could all be hokum. Gingrich sometimes sounds like that childhood friend who launched a thousand plays, soapbox derbies, and fort-building projects but never completed any of them. Or, he might not get the other kids to play along. People may not want to be engaged citizens all the time. They’ve got busy lives to lead. Training of administrative aides might wind up being as useless as lots of corporate training sessions.

But Gingrich does have his successes, chief among them the 1994 Republican victory that made him speaker. As speaker, he helped balance the budget and reform welfare. But there was also a cost. Gingrich burned out his colleagues. Today he says he pushed too much. Back then, he called them cannibals.

The other challenge for Gingrich is that his flurry of new proposals and notions bound off in so many directions that they may overwhelm even the fine-tuned Gingrich executive office of the presidency. You can strengthen the hull of your ship and get a really good navigation system, but if you go over Niagara Falls, it’s not going to matter.