ROMULUS, Mich.—My quest to discover whether the Great Newt Gingrich Surge is real has taken me to a… well, give me a second. The glowing, shifting Google map, which is only sometimes wrong, says to head to a Westin hotel at the Detroit Airport. I head there, and keep heading there, and I assume I’ve turned the wrong way until I see the average-ritzy entrance of a Westin poking out of the terminal.

Parking isn’t much easier. I have to swing around the airport road and find a spot far away in daily parking. And as for the entrance to the hotel: You have to go up, and over, and under something, then through something. I notice that a middle-aged guy carrying some coffee is looking around for directions in the same confused manner.

“Do you know where Newt is?” he asks. His name is Dave Bartleson, and he’s still shopping for candidates, but he got an e-mail about Gingrich’s hastily planned post-debate event and decided to show.

“I like how he goes after the media,” he tells me, as we descend an escalator into the Westin’s leafy lobby. “Most of us don’t like the media. Honestly, the one thing that pisses me off about him is that he had some kind of a dust-up with Glenn Beck. I don’t remember what that was all about.”

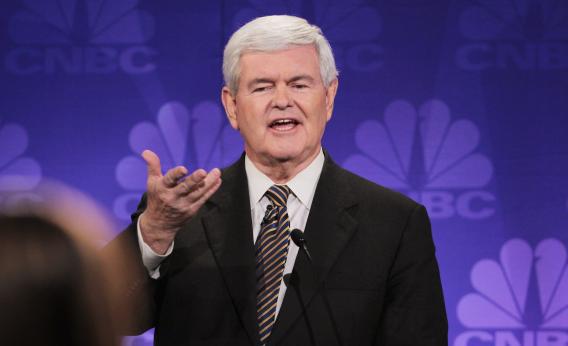

Bartleson and I finally find the room, rented in a hurry by the Gingrich campaign. There are leaflets set out pointing possible supporters to the New Contract With America at Gingrich’s website, accompanied by a short letter “from the desk of Newt Gingrich.” The man himself has already started speaking, telling around 75 people—not bad for an airport labyrinth at 8:30 a.m.—about the time he tried to get the Reagan campaign to hold an event with Republican candidates, trumpeting five big policy ideas.

“It was the first time I really encountered the Washington culture of consultants,” Gingrich remembered. “They said, ‘We don’t want to get into ideas.’ I said, ‘These are all Reagan’s ideas. These are what he campaigned on.’ ”

The room features a small stage and a podium that Gingrich isn’t using except when he needs something to lean on. There is more space for media than necessary: Besides me, there’s a CBS News reporter with a video camera and an Atlanta Journal-Constitution scribe. The rest of the press is chasing Herman Cain from Ypsilanti to Traverse City; they will get video of him saying he’s “been through hell,” and more video of him joking about Anita Hill. Meanwhile, Gingrich is talking.

“Here’s why I’m telling you the story,” says Gingrich. “David Broder wrote a very nice column about it in September of 1980. First of all, it was a huge decision by Reagan, that he was going to run as the head of a team. Second, we won six U.S. Senate seats that year. Mack Mattingly’s race in Georgia wasn’t called until the next day. If Mack Mattingly hadn’t had the ability to stand alongside Ronald Reagan and be for something, he wouldn’t have won.”

It’s a modal Newt anecdote. The villains: consultants, who are always wrong, who share the DNA of the scofflaws who quit his presidential campaign this summer and went on to join the Rick Perry juggernaut. (How’s that working out?) The heroes: people who took Gingrich seriously, led by Gingrich himself.

A lot of people wrote Gingrich into fringe territory back when his campaign collapsed. He’s now polling as high as he was before he imploded. The press understands the GOP electorate in the same way a baby-sitter understands a kid who never seems to be satisfied with the new toy: It doesn’t understand at all. Why isn’t Gingrich being punished anymore for criticizing Paul Ryan’s plan, and why are Republican voters so warm on a campaign that eschews humility for stories of the candidate’s brains and insight? There are plenty of those in the bowels of the airport hotel.

When Gingrich is asked about education spending: “Did you watch the debate? For me, personally, the most daring thing I said all evening was on college tuition.”

When he’s asked about his plans to stop judges “legislating from the bench”: “If you go to Newt.org you’ll see an entire paper on rebalancing the judiciary. It is the most thorough statement of the Constitution and the balance of power, I think, that’s been written by a political figure since Lincoln’s first inaugural in 1861.”

When he’s asked how his campaign has endured, despite all the slings and tweets and dust from the media: “Callista’s mantra was get to the debates. She said, you’ve got to find a way to survive to get to the debates. And, then frankly, the debates are a great sign of the American people’s willingness to say ’Oh, I’m actually watching him, and he doesn’t represent any of the things they’ve been describing him.’ It actually goes to one of Ronald Reagan’s great advantages. People so underestimated him going into the debates.”

This is not how any other candidate talks, which is a big reason reporters—myself included—put his campaign in the “fun curiosity” camp. And yet Republicans love it.

Talking to Newt’s fans, who had to hustle and pay for parking to show up here, you hear a few of the reasons why. There are die-hards who simply think Gingrich is a world-historical figure. Greg Hummel, one of about 50 people who hang around to have Newt and his wife sign books, says he wrote in Newt’s name for president four years ago.

The other fans sound more like Bartleson. Their resentments are the same as Newt’s. They don’t like the media, and neither does he. (In his speech he fantasizes about a Washington where home values have gone down because reporters don’t have a powerful government to cover. “That’s not the career they imagined for themselves!”) They think the media put Barack Obama in office and cover up the fact that he’s a chucklehead who can’t weld a noun to a verb without a teleprompter. Gingrich offers them the exact opposite.

Still: Why him? Why a guy who polls worse against Obama than Mitt Romney? While his spiel is captivating, in the way that a really good conservative historian is captivating, there’s no evidence that it wins over skeptics. His record, if you dig a little—that will happen, if he becomes the anti-Mitt—is as problematic as Romney’s. There’s one reason. It doesn’t have a lot to do with ideas; it has something to do with history. Cathy Fisk explains it as she heads back out of the hotel, and I ask her about Romney.

“He’s a Mormon,” she says. “I know, that sounds terrible, but in the Mormon religion they believe that Jesus and the devil are brothers—when you’re ingrained with that, it’s a problem.”

There are high-minded reasons why Gingrich is doing better these days, and why Romney can’t quite lock this down. And then there are other reasons.