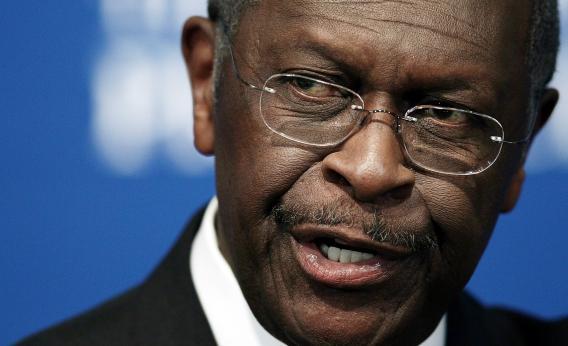

Herman Cain’s stump speech starts out talking about a nation in crisis. Now he has a campaign in one. Responding to reports about his history of sexual harassment claims, he has offered conflicting and confusing stories. The candidate known for his simplicity has fallen into lawyerly hairsplitting.

Conservatives almost immediately denounced the story as a “high-tech lynching,” the same phrase Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas (Cain’s model) used to characterize his treatment during his 1991 confirmation hearings. The expression immediately signals to partisans which setting to choose for their outrage dial. All the same, the characterization is unfair to Thomas and lets Cain off the hook.

Leave aside questions of whether the phrase “high-tech lynching” is accurate or appropriate. For our purposes, the relevant details are these: Thomas was hit with surprise allegations about sexual harassment in the middle of his confirmation hearings in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee. His former colleague Anita Hill’s allegations were new, explosive, and adjudicated by a committee unequipped for the task. It all happened under the bright lights of the hearing room, where Thomas—not a public figure or politician—had to defend himself in the middle of the circus.

The charges against Cain were handled in a far more professional manner. While Cain was chief executive of the National Restaurant Association, in at least two cases, according to Politico’s reporting and that of other news organizations, women came forward with complaints. Cain’s issue was adjudicated by lawyers and a human-resources department whose purpose, in part, is to handle these kinds of issues (if for no other reason than after the Thomas hearings every organization updated its HR policies on sexual harassment). Politics, presumably, were not involved.

Hill’s story appeared in the paper, catching Thomas off guard. Cain was given 10 days to respond to questions about the matter before it was made public. Politico wasn’t fishing—tell us anything wrong you’ve ever done—it was asking questions about a specific legal matter. Unlike Thomas, Cain wasn’t responding to a new accusation; he was being asked for his position on an issue that had already been investigated and resolved. Checks had been cut, even. Taking Cain at his word, perhaps he was only vaguely familiar with the issue when he was first asked about it. But he has a quick memory. In the 24 hours after the Politico story was published, he had a series of detailed recollections.

Is this the most important issue in the campaign? Obviously not. But it is relevant, particularly for a candidate who asks to be judged based on his performance in the private sector. As a political matter, it’s also crucial to Republicans that candidates get a thorough vetting before the general election. No less than Sarah Palin has said so. If only President Obama had gotten this kind of teeth-cleaning! Tuesday at a National Journal forum, Rick Santorum’s campaign manager said Cain’s “answers changed during the day,” as he sought to explain the harassment question, and he called on the Cain campaign to be “forthcoming so that you are vetted.”

In the Clarence Thomas matter, it was clear from the way the Hill allegations surfaced—in the middle of a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing—that they were not a part of the regular process. The same can’t be said for a presidential campaign. Cain’s knee-jerk defenders act as if this kind of story is sullying the meticulous theater of reason known as a Presidential Campaign. By the standard of presidential campaigns, and this one in particular, it’s pretty natural for candidates to have to face wacky improvised explosions. George W. Bush had to defend the alleged use of subliminal words in his advertising, and a 24-year-old DUI arrest. John McCain tried to put Obama on the hook as a sexist for using the phrase “lipstick on a pig.” Oh, and this campaign one of the former front-runners raised questions about the president’s citizenship.

Michele Bachmann was asked at a debate about submitting to her husband if she were president, based on some remarks she’d made years earlier. It was a gotcha question founded, one could argue, on a look-at-these-crazy-Christians reading of the passage she was citing.

Cain is being treated no less roughly than Cain treated others. When Rick Perry enjoyed his moment in the beating barrel over a story about a racist word written on a rock at a family hunting camp, Cain was the first rival to criticize him (and Cain, in turn, was criticized for his criticism). That Perry story wasn’t as solid as the one about Cain that he’s now denouncing, and over which conservatives are displaying such umbrage.

Thomas was treated differently than nominees that had come before him (except maybe John Tower). Cain has not been. Rather, he is simply undergoing a process known as “running for president.”

Yes, a presidential campaign is often a freak show. That’s true, and I will join you in denouncing the modern campaign freak show (I am tut-tutting as I type this, which ain’t easy). But my point is not the obvious one that the freak show is deplorable. It’s that the freak show is not going away. Every president faces it once he gets in office. Cain in most ways benefits from the freak show—the emphasis on televised debates and well-turned one-liners. Poor Rick Santorum is dragging his can through all of Iowa’s 99 counties and he’s getting nowhere. When Cain puts a foot wrong, his supporters largely let him off the hook, whereas other candidates go into free-fall in the polls.

So how did Cain handle the freak show? Not well at all. Though he’d been given time, Cain gave incomplete and misleading answers to Politico. Once the story became public, Cain’s answers were insufficient and seemed to conflict. In the morning at the National Press Club he didn’t know if there had been a settlement. By the afternoon he knew that there had been. When asked about the evolution, he sounded almost Clintonian. “I was aware an agreement was reached,” he said. “The word settlement versus the word agreement—you know, I’m not sure what they called it.”

The good news for Cain is that calling something a “high-tech lynching” is actually very helpful. Conservative voters feel like they’ve seen this movie before. They feel Thomas was unfairly treated, and regardless of whether the analogy is apt, they imagine Cain is being similarly unfairly treated. They also see recent examples to discount what the mainstream media say in the Rick Perry hunting camp story or the investigation into Sen. Marco Rubio’s family history.

Distrust of the media, plus the Cain cushion, suggest that while this is a frenzy in Washington, it won’t immediately harm him where the voting takes place. The Des Moines Register ratified this notion when it called those who had said they preferred Cain in their recent poll. None said they were jumping ship. And the Cain campaign said it had one of its best online fundraising days when the story hit. This may be another instance, for Cain at least, of a crisis turning into an opportunity.