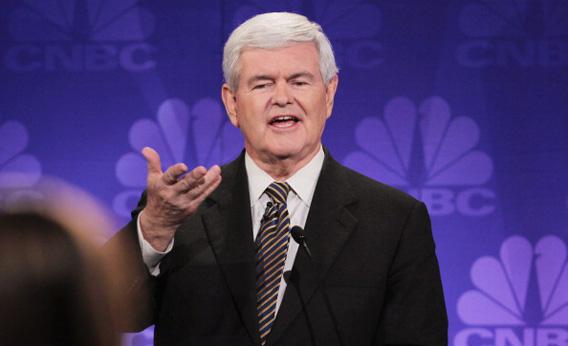

Being the non-Mitt Romney candidate in the Republican field is like being the No. 3 leader of al-Qaida: You don’t keep the job for long. Newt Gingrich’s rise starts a Doomsday clock, which counts down the minutes from the time a campaign begins to rise until it collapses. This unscientific number is based on the flameout rate of Romney’s opponents. According to the RealClearPolitics poll averages, it took two months from when Michele Bachmann started her rise to when she started to fall. That was about the same amount of time it took for Herman Cain (though his zoom back to earth is still ongoing and presumably could reverse). For Rick Perry, it took three months for the turnaround.

Gingrich’s climb started two months ago, which means he’s already passed the expiration date of two of his rivals. His ascent has been slower, but he has a month to go before setting a record for longevity.

The first challenge to Gingrich’s health came in a Bloomberg report that Freddie Mac paid him $1.5 million over eight years, including a monthly retainer of $25,000 to $30,000 for three years. Gingrich says he provided strategic advice and acted as a historian. He says he told Freddie Mac its lending guidelines were “insane,” but, like debate moderators, they didn’t listen.

If Freddie Mac paid anyone other than Gingrich that much for so little, the former speaker would use it as proof of Freddie Mac’s stupidity. Instead, the relationship offers a window into Gingrich’s wilderness years, after he resigned from Congress but still had valuable establishment credentials and Washington experience. He is now running at the top of the nominating race of a party where those two qualities were once thought disqualifying.

Sources familiar with Gingrich’s contract with Freddie Mac, as well as press accounts over the years, paint a different picture of Gingrich’s involvement. He was hired, they say, to make the case for the Freddie Mac business model just as conservatives were criticizing it. This isn’t lobbying in the sense that Gingrich asked anyone to support a specific bill. But it is common practice in Washington for enterprises like Freddie Mac (and Fannie Mae, which hired Gingrich’s former chief of staff) to keep people from Capitol Hill or the White House around, even on a monthly retainer: You never know when they might come in handy. Gingrich’s title of historian seems to be a self-appointed and recent one.

Later in the day Gingrich explained to radio host Laura Ingraham that even if he didn’t do the button-holing himself, he helped Freddie Mac’s efforts. “I may have offered advice on what they could do … if I were you I would go do this … these are the guys you ought to go talk to, and these are the things you could talk about.”

The association is problematic because Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, which have long been unpopular among conservatives, have become a central target of anti-government anger after the housing crisis. The challenge for Gingrich goes beyond demonstrating that he was not a lobbyist. He has to show he was not a part of a cozy system in which a malevolent force uses the power of a former speaker to protect its special-interest status.

Michele Bachmann was the first of Gingrich’s rivals to hit this theme: “While he was taking that money, I was fighting against Fannie and Freddie.” (Bachmann was, however, taking campaign donations.)

In a brief press conference Wednesday, Gingrich explained that the episode shows why he should be president. “It reminds people that I know a great deal about Washington and if you want to change Washington, we just tried four years of amateur ignorance and it didn’t work very well, so having somebody who knows Washington might be a really good thing.”

It was about time that someone defended the benefits of political experience, if for no other reason than to reset the balance. There has been a little too much unqualified praise for complete ignorance of Washington. But if the GOP buys the Gingrich line it will be quite a change: Gingrich, with his Washington experience and insider know-how, will replace Herman Cain, whose success was founded on the idea that he had neither of those qualities.

The question for voters is whether Gingrich’s experience is what they want. His record as a leader in Washington is about to get a thorough airing. He achieved a lot but he also broke some furniture and created a lot of enemies, many of them in his own party. If the Republican contest comes down to a battle between Gingrich’s management experience in Washington and Romney’s management experience in business, it may be a hard sell for Gingrich. On the other hand, maybe Gingrich can argue that he is both an experienced Washington hand and an outsider who challenges the ways of Washington. It’s an argument uniquely suited to a former speaker who was run out of town.