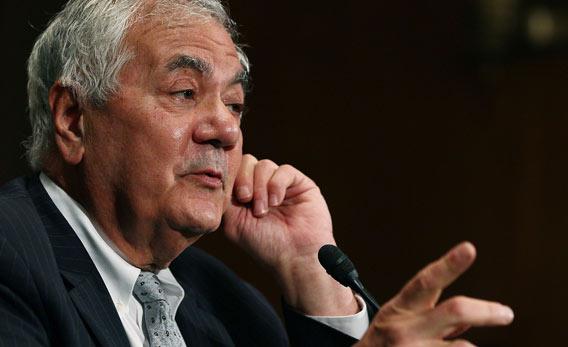

Politicians like to use retirement speeches to criticize the systems that have so disappointed them. Rep. Barney Frank embraced that tradition on Monday with his copyrighted mix of derision and bluntness.

“People on the left and people on the right live in parallel universes,” he mused. “No longer do people get their information from a common media source, and then diverge in how they interpret it. The left is on MSNBC and on the blogs. The right is on Fox and on talk radio. And what happens is, people know different facts. These are echo chambers. People hear agreement with themselves.”

The point he was trying to make: Voters needed to share some of the blame for how lousy their government had become. They hustled moderates out of office, and they demanded crazy things of people like Frank. Still: sad denunciations of our polarized media? Really? Didn’t Evan Bayh cover that when he retired?

It was strange to hear Frank tooting from that bugle. Polarized media and political debate has generally been better for Republicans than it’s been for Democrats. One exception was Barney Frank. No liberal politician—none who had to face voters every two years—was so at home in the culture wars.

Frank’s policy legacy, as his friends said all day Monday, will rest on two pieces of legislation that voters either loathe, misunderstand, or loathingly misunderstand. He headed the House Financial Services committee for four years. He helped craft the Troubled Asset Relief Program (there were grousers who said the first version of it failed the House because Frank didn’t demand enough controls), and he won the agonizing battle for post-collapse Wall Street reform. The first bill was the animus for the greatest conservative voter rebellion in 30 years. The second, according to nervous Democrats, is in serious danger from Republicans who pledge to undo it if they romp in 2012.

One reason for the angst is that Frank is—sorry again, was—so good at explaining what he was trying to do. Any critic or journalist who challenged Frank would soon learn that he was stupid, that he wasn’t listening, or that he had foolishly failed to consider one of a thousand or so other facts that Frank had memorized. While Frank was making his Monday announcement, reporters were swapping stories of the times Frank had first shut them down for being imbeciles. Mine was in January, when I tried to follow up something Frank had said about the impossibility of gun control even after the assassination attempt on Rep. Gabrielle Giffords. “Don’t argue with me,” he said. “I’m telling you what they say, and you’re going to give me a logical argument for it?” If I’d written Frank an angry letter, I might have gotten the response he once sent to a crank in his district: “I’m surprised to find absence of explicit anti-Semitism this time. Was a page missing?”

This was how Frank talked. Other liberals may have been comfortable having friendly tiffs like this. But Frank was atypically comfortable getting into these sorts of spats over cultural issues. The culture wars were designed by conservatives so that conservatives would always win. Frank simply didn’t care if most Americans agreed with the conservative position on religion, gay rights, abortion, or drug laws. In 1984, when he was in his second term and presiding over early morning speeches, Frank got irritated when Rep. Marjorie Holt, R-Md., pined for America to rediscover its identity as a “Christian nation.”

“If this is a Christian nation,” said Frank, “how come some poor Jew has to get up at 5:30 in the morning to preside over the House of Representatives?” Even after Holt retracted the comment—really, the kind of comment made 100 times a day on campaign trails—Frank dug in. “I’ve never met a Judeo-Christian,” he snarked. “What do they look like? What kind of card do you send them in December?” A reporter asked him to explain himself further. “I have no objection to Christians being more Christian,” he said. “I object to them making America more Christian.”

There’s no upside to talking like this, at least in national politics. Frank turned this around. He talked about morality the way that conservatives talked about it. He was obviously right; the other side was full of hypocrites and morons. In the 1996 debate over the Defense of Marriage Act, which came without much warning, Frank mocked Republicans for fearing that some marriage-destroying power could jump from host to host like a virus.

“How does the fact that I love another man and live in a committed relationship with him threaten your marriage?” asked Frank in floor debate. “Are your relations with your spouses of such fragility that the fact I have a committed, loving relationship with another man jeopardizes them?”

The other side was always wrong, always misinformed, probably nuts. In 2009 and 2010, when other Democrats were enfeebled by unexpected Tea Party attacks, Frank would shut down anyone who challenged him in public. In 2009 a Harvard Law student named Joel Pollak asked Frank if he deserved some blame for the financial crisis, and Frank derided him for indulging a “right-wing attack.” Pollak would go on to run for Congress himself in Illinois, and lose, but he didn’t claim to have out-debated Frank.

“What separates Barney Frank from other left-wing ideologues is that his posture of intellectual superiority rises to the level of genuine conviction,” said Pollak in an email. (He’s now the editor of Andrew Breitbart’s “Big” blogs.) “In a pinch, he can batter his opponents with encyclopedic details about historical events and legislative minutiae. He’s an ‘intellectual bully,’ though there’s often no insight in his insults, just evasion and question-begging.”

There’s a lot of that in political debate, though. What’s lacking are liberals who are good at it. “His humor works because he seems naturally funny and off the cuff,” said Sam Seder, a former Air America host and roving TV pundit who booked Frank when he could. “I think his entire appeal as a guest comes from his not seeming to try too hard.”

It doesn’t sound hard, but it is. You can now choose your own media, your own political news, and your own facts. Nobody’s going to break into your silo unless he’s loud, and he can explain why you’re so stupid.